RESULTS

Prior to this QI initiative launch, 14 awards were given out over the preceding 2-year period. During the initial 18 months of the initiative (December 2020 to June 2022), 59 awards were presented (Level 1, n = 26; Level 2, n = 22; and Level 3, n = 11). Looking further into the Level 1 awards presented, 25 awardees worked in clinical roles and 1 in a nonclinical position (Table 2). The awardees represented multidisciplinary areas, including medical/surgical (med/surg) inpatient units, anesthesia, operating room, pharmacy, mental health clinics, surgical intensive care, specialty care clinics, and nutrition and food services. With the Level 2 awards, 18 clinical staff and 4 nonclinical staff received awards from the areas of med/surg inpatient, outpatient surgical suites, the medical center director’s office, radiology, pharmacy, primary care, facilities management, environmental management, infection prevention, and emergency services. All Level 3 awardees were from clinical areas, including primary care, hospital education, sterile processing, pharmacies, operating rooms, and med/surg inpatient units.

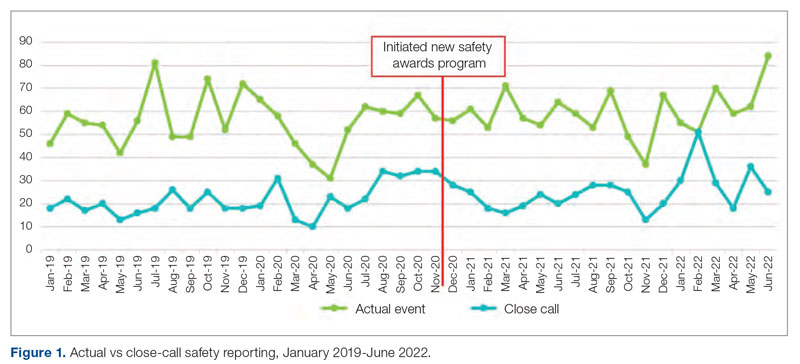

With the inception of this QI initiative, our organization has begun to see trends reflecting increased reporting of both actual and close-call events in JPSR (Figure 1).

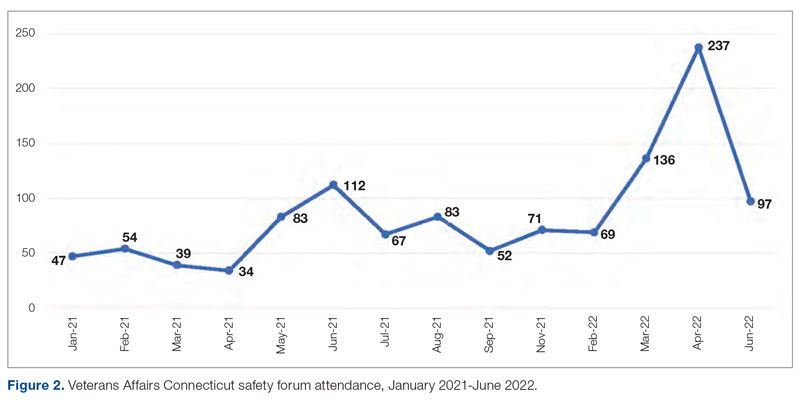

With the inclusion of information regarding awardees and their actions in monthly safety forums, attendance at these forums has increased from an average of 64 attendees per month in 2021 to an average of 131 attendees per month in 2022 (Figure 2).

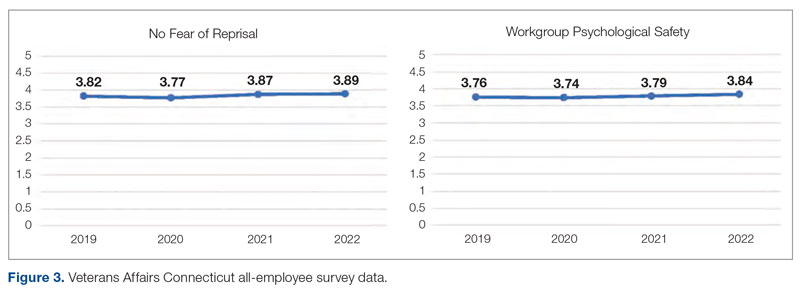

Finally, our organization’s annual All-Employee Survey results have shown incremental increases in staff reporting feeling psychologically safe and not fearing reprisal (Figure 3). It is important to note that there may be other contributing factors to these incremental changes.

Stories From the 3 Award Categories

Level 1 – Good Catch Award. M.S. was assigned as a continuous safety monitor, or “sitter,” on one of the med/surg inpatient units. M.S. arrived at the bedside and asked for a report on the patient at a change in shift. The report stated that the patient was sleeping and had not moved in a while. M.S. set about to perform the functions of a sitter and did her usual tasks in cleaning and tidying the room for the patient for breakfast and taking care of all items in the room, in general. M.S. introduced herself to the patient, who she thought might wake up because of her speaking to him. She thought the patient was in an odd position, and knowing that a patient should be a little further up in the bed, she tried with touch to awaken him to adjust his position. M.S. found that the patient was rather chilly to the touch and immediately became concerned. She continued to attempt to rouse the patient. M.S. called for the nurse and began to adjust the patient’s position. M.S. insisted that the patient was cold and “something was wrong.” A set of vitals was taken and a rapid response team code was called. The patient was immediately transferred to the intensive care unit to receive a higher level of care. If not for the diligence and caring attitude of M.S., this patient may have had a very poor outcome.

Reason for criteria being met: The scope of practice of a sitter is to be present in a patient’s room to monitor for falls and overall safety. This employee noticed that the patient was not responsive to verbal or tactile stimuli. Her immediate reporting of her concern to the nurse resulted in prompt intervention. If she had let the patient be, the patient could have died. The staff member went above and beyond by speaking up and taking action when she had a patient safety concern.

Level 2 – HRO Safety Champion Award. A patient presented to an outpatient clinic for monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy for a COVID-19 infection; the treatment has been scheduled by the patient’s primary care provider. At that time, outpatient mAb therapy was the recommended care option for patients stable enough to receive treatment in this setting, but it is contraindicated in patients who are too unstable to receive mAb therapy in an outpatient setting, such as those with increased oxygen demands. R.L., a staff nurse, assessed the patient on arrival and found that his vital signs were stable, except for a slightly elevated respiratory rate. Upon questioning, the patient reported that he had increased his oxygen use at home from 2 to 4 L via a nasal cannula. R.L. assessed that the patient was too high-risk for outpatient mAb therapy and had the patient checked into the emergency department (ED) to receive a full diagnostic workup and evaluation by Dr. W., an ED provider. The patient required admission to the hospital for a higher level of care in an inpatient unit because of severe COVID-19 infection. Within 48 hours of admission, the patient’s condition further declined, requiring an upgrade to the medical intensive care unit with progressive interventions. Owing to the clinical assessment skills and prompt action of R.L., the patient was admitted to the hospital instead of receiving treatment in a suboptimal care setting and returning home. Had the patient gone home, his rapid decline could have had serious consequences.

Reason for criteria being met: On a cursory look, the patient may have passed as someone sufficiently stable to undergo outpatient treatment. However, the nurse stopped the line, paid close attention, and picked up on an abnormal vital sign and the projected consequences. The nurse brought the patient to a higher level of care in the ED so that he could get the attention he needed. If this patient was given mAb therapy in the outpatient setting, he would have been discharged and become sicker with the COVID-19 illness. As a result of this incident, R.L. is working with the outpatient clinic and ED staff to enahance triage and evaluation of patients referred for outpatient therapy for COVID-19 infections to prevent a similar event from recurring.

Level 3 – Culture of Safety Appreciation Award. While C.C. was reviewing the hazardous item competencies of the acute psychiatric inpatient staff, it was learned that staff were sniffing patients’ personal items to see if they were “safe” and free from alcohol. This is a potentially dangerous practice, and if fentanyl is present, it can be life-threatening. All patients admitted to acute inpatient psychiatry have all their clothing and personal items checked for hazardous items—pockets are emptied, soles of shoes are lifted, and so on. Staff wear personal protective equipment during this process to mitigate any powders or other harmful substances being inhaled or coming in contact with their skin or clothes. The gloves can be punctured if needles are found in the patient’s belongings. C.C. not only educated the staff on the dangers of sniffing for alcohol during hazardous-item checks, but also looked for further potential safety concerns. An additional identified risk was for needle sticks when such items were found in a patient’s belongings. C.C.’s recommendations included best practices to allow only unopened personal items and have available hospital-issued products as needed. C.C. remembered having a conversation with an employee from the psychiatric emergency room regarding the purchase of puncture-proof gloves to mitigate puncture sticks. C.C. recommended that the same gloves be used by staff on the acute inpatient psychiatry unit during searches for hazardous items.

Reason for criteria being met: The employee works in the hospital education department. It is within her scope of responsibilities to provide ongoing education to staff in order to address potential safety concerns.