Methods

Setting

Banner Health is a non-profit, multi-hospital health care system across 6 states in the western United States that is uniquely positioned to study provider quality attribution models. It not only has a large number of providers and serves a broad patient population, but Banner Health also uses an instance of Cerner (Kansas City, MO), an enterprise-level electronic health record (EHR) system that connects all its facilities and allows for advanced analytics across its system.

For this study, we included only general medicine and surgery patients admitted and discharged from the inpatient setting between January 1, 2018, and December 31, 2018, who were between 18 and 89 years old at admission, and who had a LOS between 1 and 14 days. Visit- and patient-level data were collected from Cerner, while outcome data, and corresponding expected outcome data, were obtained from Premier, Inc. (Charlotte, NC) using their CareScience methodologies.10 To measure patient experience, response data were extracted from post-discharge surveys administered by InMoment (Salt Lake City, UT).

Provider Attribution Models

Provider Attribution by Physician of Record (PAPR). In the standard approach, denoted here as the PAPR model, 1 provider—typically the attending or discharging provider, which may be the same person—is attributed to the entire hospitalization. This provider is responsible for the patient’s care, and all patient outcomes are aggregated and attributed to the provider to gauge his or her performance. The PAPR model is the most popular form of attribution across many health care systems and is routinely used for P4P incentives.

In this study, the discharging provider was used when attributing hospitalizations using the PAPR model. Providers responsible for fewer than 12 discharges in the calendar year were excluded. Because of the directness of this type of attribution, the performance of 1 provider does not account for the performance of the other rotating providers during hospitalizations.

Provider Attribution by Multiple Membership (PAMM). In contrast, we introduce another attribution approach here that is designed to assign partial attribution to each provider who cares for the patient during the hospitalization. To aggregate the partial attributions, and possibly control for any exogenous or risk-based factors, a multiple-membership, or multi-member (MM), model is used. The MM model can measure the effect of a provider on an outcome even when the patient-to-provider relationship is complex, such as in a rotating provider environment.8

The purpose of this study is to compare attribution models and to determine whether there are meaningful differences between them. Therefore, for comparison purposes, the same discharging providers using the PAPR approach are eligible for the PAMM approach, so that both attribution models are using the same set of providers. All other providers are excluded because their performance would not be comparable to the PAPR approach.

While there are many ways to document provider-to-patient interactions, 2 methods are available in almost all health care systems. The first method is to link a provider’s billing charges to each patient-day combination. This approach limits the attribution to 1 provider per patient per day because multiple rotating providers cannot charge for the same patient-day combination.3 However, many providers interact with a patient on the same day, so using this approach excludes non-billed provider-to-patient interactions.

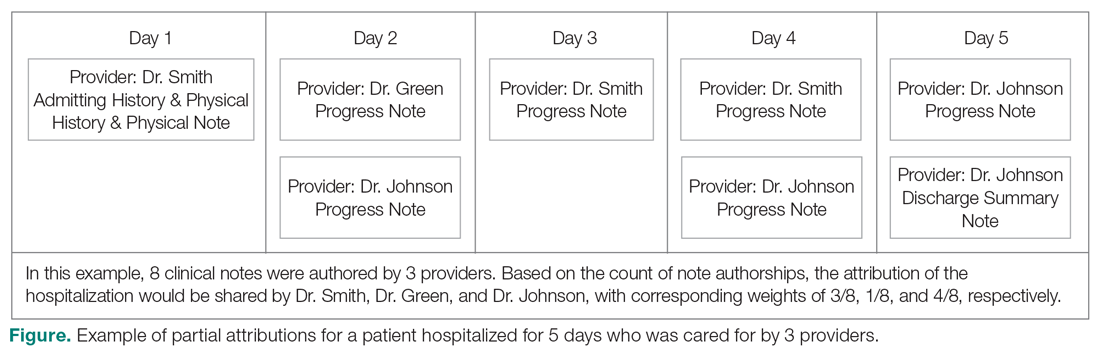

The second method, which was used in this study, relies on documented clinical notes within the EHR to determine how attribution is shared. In this approach, attribution is weighted based on the authorship of 3 types of eligible clinical notes: admitting history/physical notes (during admission), progress notes (during subsequent days), and discharge summary notes (during final discharge). This will (likely) result in many providers being linked to a patient on each day, which better reflects the clinical setting (Figure). Recently, clinical notes were used to attribute care of patients in an inpatient setting, and it was found that this approach provides a reliable way of tracking interactions and assigning ownership.11

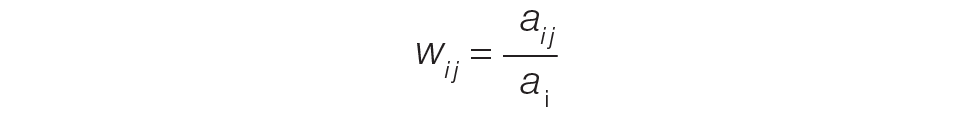

The provider-level attribution weights are based on the share of authorships of eligible note types. Specifically, for each provider j, let aij be the total count of eligible note types for hospitalization i authored by provider j, and let ai be the overall total count of eligible note types for hospitalization i. Then the attribution weight is

(Eq. 1)

for hospitalization i and provider j. Note that ∑jwij = 1: in other words, the total attribution, summed across all providers, is constrained to be 1 for each hospitalization.

Patient Outcomes

Outcomes were chosen based on their routine use in health care systems as standards when evaluating provider performance. This study included 6 outcomes: inpatient LOS, inpatient mortality, 30-day inpatient readmission, and patient responses from 3 survey questions. These outcomes can be collected without any manual chart reviews, and therefore are viewed as objective outcomes of provider performance.

Each outcome was aggregated for each provider using both attribution methods independently. For the PAPR method, observed-to-expected (OE) indices for LOS, mortality, and readmissions were calculated along with average patient survey scores. For the PAMM method, provider-level random effects from the fitted models were used. In both cases, the calculated measures were used for ranking purposes when determining top (or bottom) providers for each outcome.