Results

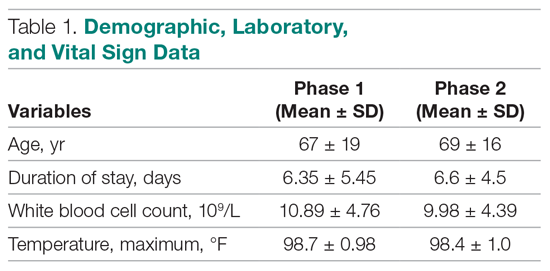

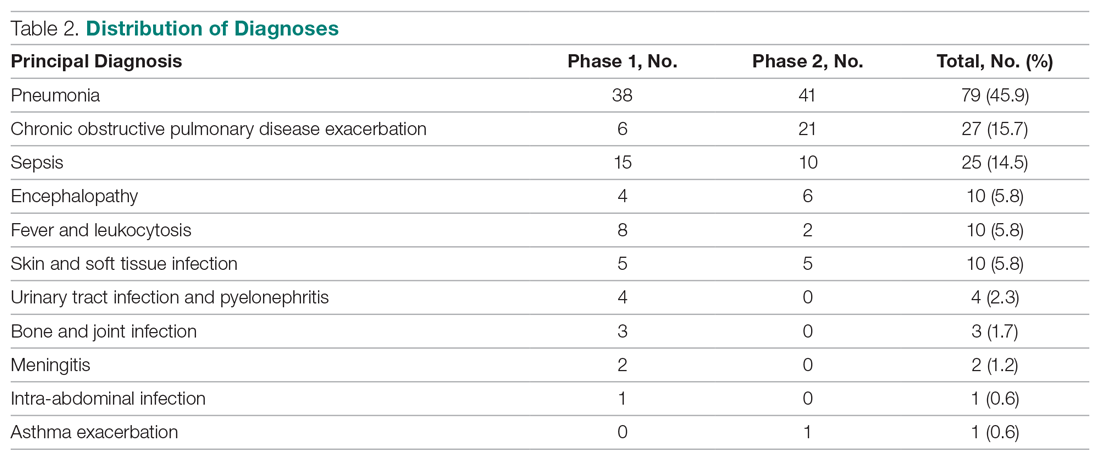

A total of 172 patients were included in this study: 86 patients prior to the intervention, and 86 after implementation. Baseline demographics, laboratory values, vitals, and principal diagnoses for both groups are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. The most common indications for procalcitonin measurement were pneumonia (45.9%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (15.7%), and sepsis (14.5%). The remaining diagnoses were encephalopathy, fever and leukocytosis, skin and soft tissue infection, urinary tract infection or pyelonephritis, bone and joint infection, meningitis, intra-abdominal infection, and asthma exacerbation.

Antibiotic therapy was initiated in 68% of the patients overall, 59% in the baseline group and 76% in the intervention group. The duration of antibiotic use was not significantly different between the baseline (3.14 ± 4.04 days) and intervention (3.34 ± 2.8 days) groups (P = 0.1083). Furthermore, antibiotic treatment duration did not vary significantly with patient age, white blood cell count, maximum temperature, or procalcitonin level in either group. Although there was no difference in total antibiotic treatment duration, a post-hoc analysis revealed a 0.6-day decrease in the interval between the date of procalcitonin measurement and the stop date of antibiotics in the intervention group. The average time from admission to obtaining a procalcitonin level was 3 days in the baseline group and 2 days in the intervention group.

Discussion

Our study did not demonstrate a difference in total antibiotic treatment duration with procalcitonin measurement and an oral communication intervention made by a clinical pharmacist at a community teaching hospital with a well-established antimicrobial stewardship program. This may be due to several factors. First, the providers did not receive ongoing education regarding the appropriate use or interpretation of procalcitonin. The procalcitonin result in the electronic health record references the risk for progression to severe sepsis and/or septic shock, but does not indicate how to use procalcitonin as an aid in antibiotic decision-making. However, a recent study in patients with lower respiratory tract infections treated by providers who had been educated on the use of procalcitonin failed to find a reduction in total antibiotic use.9 Second, our study included hospital-wide use of procalcitonin, and was not limited to infections for which procalcitonin use has the strongest evidence (eg, upper respiratory tract infections, pneumonia, sepsis). Thus, providers may have been less likely to use protocolized guidelines. Last, we did not limit the data on antibiotic duration to patients with a procalcitonin level obtained within a defined time frame from antibiotic initiation or time of admission, and some patients had procalcitonin levels measured several days into their hospital stay. While this is likely to have skewed the data in favor of longer antibiotic treatment courses, it also represents a more realistic way in which this laboratory test is being used. Our post-hoc finding of earlier discontinuation of antibiotics after procalcitonin measurement suggests that our intervention may have influenced the decision to discontinue antibiotics. Such an effect may be augmented if procalcitonin is measured earlier in a hospital admission.