Analysis

SPSS Statistics (Version 24) was used to conduct analyses. Independent sample t tests were employed to measure items related to the provider educational sessions. Mean provider responses for each item were reviewed from descriptive statistics. A chi-square cross tabulation was used to compare the percentage of patients receiving a Behavior Management Plan that adhered to follow-up visits versus a similar sample of patients that presented in 2016 before the introduction of the Behavior Management Plan. In addition, a chi-square cross tabulation was utilized to compare adherence to follow-up visits in those that received the Management Plan to that of eligible patients that presented during the same time period but did not receive the Plan. Additional chi-square tests were run to see if there was any difference in 2017 follow-up rates based on individual provider or visit type .

Results

Provider Questionnaire

Six providers responded to the pre-intervention questionnaire and five to the post-intervention questionnaire. The specific questions and their results are listed in Table 1.

Patient Management

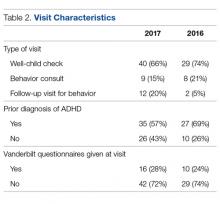

Between April and May 2017, 61 eligible patients presented to the clinic. Details of the breakdown of patient visit type are displayed in Table 2.

The majority of patients presented with concerns during their well-child visits. Over half of patients presenting for behavioral concerns (57%) already had a diagnosis of ADHD. Of those without a previous diagnosis, Behavior Management Plans were given during 52% (13 of 25) of visits. Two patients with an active diagnosis of ADHD were given Behavior Management Plans as changes to their medications or treatment plans were made.Follow-up Rates

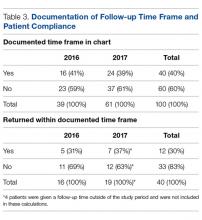

Notation of a specific time frame for follow-up by a primary care provider was found in 24 of 61 (39%) relevant patient charts (Table 3).

Five patients were given follow-up times beyond the time frame of the study; therefore, calculations were based on the remaining 19 patients that were given specific instructions to follow-up in clinic before June of 2017. Seven (37%) returned for their follow-up visit within the time frame given by their provider during their initial visit and 12 patients (63%) failed to show during their advised follow-up period. A chi-square test confirmed that there was no significant difference in the follow-up rates between the intervention and prior year that was used for comparison (P = 0.99).Further cross-tabulations were completed to assess if there were better follow-up rates for patients that received a Behavior Management Plan. The difference between the 2 groups was not significant (P = 0.99). There were no significant differences found in follow-up rates based on the provider for the visit (P = 0.51) or the type of patient visit (well child examination vs. behavior consult) (P = 0.65).

Discussion

This project aimed to improve provider confidence in the assessment and treatment of ADHD and improve ADHD management by providers at our clinic. We did not find significant changes in confidence according to the survey results. However, provider feedback indicated that, as a result of the educational sessions, they had a deeper appreciation for the presence of psychiatric comorbidities and the role they play in deciding appropriate treatment. They also reported that they more fully understood the need to refer to child psychiatry for evaluation and management when comorbidities are present instead of attempting to independently provide ADHD medication.

We hoped to see the Behavior Management Plan used for patients with new behavior concerns during the evaluation for ADHD. During the intervention period, it was used in half of eligible clinic visits of patients without a prior diagnosis of ADHD. Future investigation should be directed at receiving specific input on the utility of the Behavior Management Plan from providers and families. The Management Plan contains important reminders and treatment information; however, if the plan is not perceived as effective or useful, taking the time needed to complete it may be seen as an additional cumbersome step in the already overloaded clinic visits.

The use of the Behavior Management Plan was not found to make a statistically significant difference in follow-up rates. Attendance at follow-up appointments for ADHD patients is not an area that has been greatly studied. In a recent analysis of ADHD treatment quality in Medicaid-enrolled children, African American families were less likely to have adequate follow-up compared to Caucasian counterparts during the initiation or continuation and management phases of treatment. The review of specific follow-through rates showed that African Americans were 22% more likely to discontinue medication therapy and 13% more likely to disengage from treatment. The authors propose that future efforts focus on improving accessibility of behavioral therapy to combat the discontinuation rates and disparities in this area [8]. Another study that looked at a prospective cohort of ADHD patients found suboptimal attendance at appointments with a median of 1 visit every 6 months [9]. Further exploration of the challenges with attendance at follow-up appointments is warranted to help determine best practices for ADHD management in disadvantaged communities. More information is needed on the specific barriers to care in this subgroup at our clinic. However, data from this project related to adherence to follow-up appointments can be used to guide future studies.

Use of a Behavior Management Plan was not found to influence the return of completed teacher Vanderbilt scales by families. The rates of return of these assessment forms continue to be very low. Without input from teachers and schools, it is difficult to properly diagnose, treat and evaluate the treatment of patients. Feedback from all sources is essential for both medication management and construction of interventions for behavioral challenges at school. The development of partnerships with a child’s school may be useful in helping patients return for the treatment of behavior concerns at their initial stages. Before children are expelled multiple times due to their behavior, schools should strongly encourage parents to notify their healthcare provider of behavior concerns for evaluation.

In an ideal system, school-based nurses, guidance counselors or social workers could provide some case management and outreach to families of children with known behavior concerns to ensure they are attending appointments as recommended by their treatment plan and explore barriers to doing so. Social workers can provide direct mental health care services and make referrals to community agencies. However, the caseload for school-based providers is currently quite high and many children slip through the cracks until their behavior escalates to a dangerous and/or very disruptive level. School-based personnel in several districts are now required to split their time in multiple schools. Dang et al describe the piloting of a school-based framework for early identification and assessment of children suspected to have ADHD. The framework, called ADHD Identification and Management in Schools (AIMS), encourages school nurses to gather all parent and teacher assessment materials prior to the initial visit to their primary care providers thus reducing the number of visits needed and leading to faster diagnosis and treatment [10].

Clinic-based case managers solely dedicated to this population would also be useful. These case managers could provide management as described above and also potentially sit-in on clinic visits for behavior concerns so that they are fully aware of the instructions given by the provider. This would also give them the information needed so that they are able to complete forms such as the Behavior Management Plan, which would be helpful in relieving some provider time. Geltman et al trialed a workflow intervention with electronic Vanderbilt scales and an electronic registry managed by a care coordination team of a physician, nurse and medical assistant. This allowed patient calls to the families by the nurse or medical assistant to remind them of necessary follow-up and monthly meetings with the care coordination team. Those in the intervention group with the care coordination team were twice as likely to return the Vanderbilt questionnaires. During the intervention period, the rates of follow-up visits remained the same; however, when the intervention was further adopted and expanded to other sites, follow-up attendance improved to over 90% [11].