What are diagnostic criteria for migraine?

Diagnosis of migraine is performed according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) [29]. Based on the number of headache days that the patient reports, migraine is classified into episodic or chronic migraine. Migraines that occur on fewer than 15 days/month are categorized as episodic migraines.

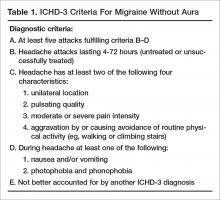

Episodic migraine is divided into 2 categories: migraine with aura (Table 1) and migraine without aura. Migraine without aura is described as recurrent headaches consisting of at least 5 attacks, each lasting 4 to 72 hours if left untreated. At least 2 of the following 4 characteristics must be present: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, with aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. During headache, at least 1 of nausea and/or vomiting or photophobia and phonophobia should be present.

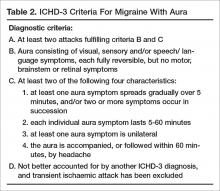

In migraine with aura (Table 2), headache characteristics are the same, but in addition there are at least 2 lifetime attacks with fully reversible aura symptoms (visual, sensory, speech/language). In addition, these auras have at least 2 of the following 4 characteristics: at least 1 aura symptom spreads gradually over 5 minutes, and/or 2 or more symptoms occur in succession; each individual aura symptom lasts 5 to 60 minutes; aura symptom is unilateral; and aura is accompanied, or followed within 60 minutes, by headache. Migraine with aura is uncommon, occurring in 20% of patients with migraine [30]. Visual aura is the most common type of aura, occurring in up to 90% of patients [31]. There is also aura without migraine, called typical aura without headache. Patients can present with non-migraine headache with aura, categorized as typical aura with headache [29].

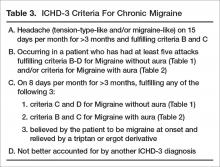

Headache occurring on 15 or more days per month for more than 3 months, which has the features of migraine headache on at least 8 days per month, is classified as chronic migraine (Table 3). Evidence indicates that 2.5% of episodic migraine progresses to chronic migraine over 1-year follow-up [32]. There are several risk factors for chronification of migraine. Nonmodifiable factors include female sex, white European heritage, head/neck injury, low education/socioeconomic status, and stressful life events (divorce, moving, work changes, problems with children). Modifiable risk factors are headache frequency, acute medication overuse, caffeine overuse, obesity, comorbid mood disorders, and allodynia. Acute medication use and headache frequency are independent risk factors for development of chronic migraine [33]. The risk of chronic migraine increases exponentially with increased attack frequency, usually when the frequency is ≥ 3 headaches/month. Repetitive episodes of pain may increase central sensitization and result in anatomical changes in the brain and brainstem [34].

What information should be elicited during the history?

Specific questions about the headaches can help with making an accurate diagnosis. These include:

- Length of attacks and their frequency

- Pain characteristics (location, quality, intensity)

- Actions that trigger or aggravate headaches (eg, stress, movement, bright lights, menses, certain foods and smells)

- Associated symptoms that accompany headaches (eg, nausea, vomiting)

- How the headaches impact their life (eg, missed days at work or school, missed life events, avoidance of social activities, emergency room visits due to headache)

To assess headache frequency, it is helpful to ask about the number of headache-free days in a month, eg, “how many days a month do you NOT have a headache.” To assist with headache assessment, patients can be asked to keep a calendar in which they mark days of use of medications, including over the counter medications, menses, and headache days. The calendar can be used to assess for migraine patterns, headache frequency, and response to treatment.

When asking about headache history, it is important for patients to describe their untreated headaches. Patients taking medications may have pain that is less severe or disabling or have reduced associated symptoms. Understanding what the headaches were like when they did not treat is important in making a diagnosis.

Other important questions include when was the first time they recall ever experiencing a headache. Migraine is often present early in life, and understanding the change in headache over time is important. Also ask patients about what they want to do when they have a headache. Often patients want to lie down in a cool dark room. Ask what they would prefer to do if they didn’t have any pending responsibilities.

Comorbidities

Comorbidities are commonly seen with migraine. Common comorbidities are mood disorders (depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder), musculoskeletal disorders (neck pain, fibromyalgia, Ehlors-Danlos syndrome), sleep disorders, asthma, allergies, thyroid dysfunction, obesity, irritable bowel syndrome, epilepsy, stroke, and heart disease.

Comorbid conditions can increase migraine disability and also can provide information about the pathophysiology of migraine and guide treatment. Management of the underlying comorbidity often leads to improved migraine outcomes. For example, serotonergic dysfunction is a possible pathway involved in both migraine and mood disorders. Treatment with medications that alter the serotonin system may help both migraine and coexisting mood disorders. Bigal et al proposed that activation of the HPA axis with reduced serotonin synthesis is a main pathway involved in affective disorders, migraine, and obesity [35].

In the early 1950s, Wolff conceptualized migraine as a psychophysiologic disorder [36]. The relationship between migraine and psychiatric conditions is complex, and comorbid psychiatric disorders are risk factors for headache progression and chronicity. Psychiatric conditions also play a role in nonadherence to headache medication, which contributes to poor outcome in these patients. Hence, there is a need for assessment and treatment of psychiatric disorders in people with migraine. A study by Guidetti et al found that headache patients with multiple psychiatric conditions have poor outcomes, with 86 % of these headache patients having no improvement and even deterioration in their headache [37]. Another study by Mongini et al concluded that psychiatric disorder appears to influence the result of treatment on a long-term basis [38].

In addition, migraine has been shown to impact mood disorders. Worsening headache was found to be associated with poorer prognosis for depression. Patients with active migraine not on medications with comorbid major depressive disorder (MDD) had more severe anxiety and somatic symptoms as compared with MDD patients without migraine [39].