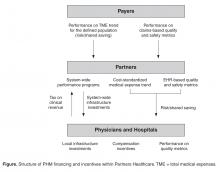

Any organization involved in multiple performance based risk contracts faces the challenge of organizing the tactics and metrics for their providers. It is simply inconsistent with provider values and workflow to manage to different targets for different subpopulations of patients. In our attempts to promote the best possible care for all our patients and at the same time meet the demands of multiple external contract requirements, we have created an internal performance framework (IPF) that uses a single set of performance targets and a single incentive pool for all out contracts. The IPF rewards member institutions for (1) adopting programmatic initiatives (funded through the tax as described above), (2) meeting external quality measure targets, and (3) limiting the growth of cost-standardized medical expense trend ( Figure).

We anticipate that limiting the number of measures providers need to focus on at any one time will have a “spillover effect” on the corresponding externally defined measures. For example, some of our internal metrics focus on diabetes outcomes measures, with the expectation that performance on externally defined diabetes screening measures should follow. Simplifying external measures to a thoughtful set of internal performance expectations measured using actual clinical data rather than claims helps providers within an ACO focus on a core set of credible performance objectives, as opposed to an array of seemingly conflicting and overwhelming external contractual obligations. We continue to calibrate the magnitude of the incentive and the periodicity of measurement, but to date have been impressed that relatively small incentives and a bi-annual cycle time can have powerful impacts [5].Fixing Primary Care

Populations in risk contracts are typically defined by their primary care providers. In addition, the chronic underfunding of primary care in the US has resulted in unsustainable practice environments as well as well known access problems. Finally, the concentration of costs in a relatively small proportion of patients provides the greatest opportunity for ACOs to reduce costs through better care coordination for these patients. This core set of facts has guided our efforts to improve primary care. To address these issues, we have increased funding to primary care through our efforts to certify all 236 practices as patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs). In addition, we have begun transitioning our compensation models to include components based on risk-adjusted panel size and performance on quality metrics. As mentioned above, we have invested heavily in our complex care management program. Finally, we are working on a much tighter integration of mental health services with primary care. In this section we focus on lessons from our care management program and our efforts in mental health integration.

Complex Care Management

Provider-led high-risk care management has become the primary clinical lever for cost containment for most accountable care organizations [6]. The design and operational characteristics or our program have been described by Hong et al and are available on our website. Our decade of experience with this program has taught us a few lessons regarding the use of algorithms to identify patients, the management of program costs, and the difficulty of creating meaningful accountability.