Pharmacist Evaluation

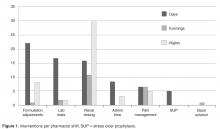

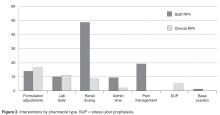

Decentralized pharmacists performed 81% ( n = 118) of interventions. Fifty-two percent ( n = 76) were made during day shift between 0700 and 1500, 15% ( n = 21) on evenings between 1500 and 2300, and 33% ( n = 48) on nights between 2300 and 0700. The types of interventions made by each shift differed ( Figure 1 ). Staff pharmacists performed 71% ( n = 103) of all interventions compared to 29% by clinical pharmacists ( n = 42) ( Figure 2 ). Some intervention categories were performed by only one pharmacist type. Differentiation of pain management orders were performed only by staff pharmacists while stress ulcer prophylaxis was performed only by the critical care clinical pharmacist. No pattern existed in regard to day of week on which interventions were made.Prescriber Evaluation

An evaluation of prescribers revealed that the primary physician groups (ie, order generators) involved were hospitalists ( n = 32) and critical care attendings ( n = 24) at 22% and 17% of all orders, respectively. The remaining 89 interventions were distributed across other attending types (including general medicine physicians, specialty physicians and surgeons) and trainees (residents and fellows) with no more than eight orders for any individual physician category.

Protocol Evaluation

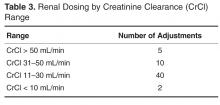

The renal dosing protocol was the most commonly used, representing 39.3% ( n = 57) of all changes, followed by dose formulation changes at 21.3% ( n = 31). Enoxaparin, levofloxacin, and vancomycin were involved in 80% of all renal dose adjustments made with the most common creatinine clearance range involved being 11–30 mL/min ( Table 3 ). Gastrointestinal agents (ie, docusate, famotidine, pantoprazole, senna) and antimicrobials (ie, levofloxacin, fluconazole, metronidazole) were involved most commonly in formulation adjustments.The total number of laboratory tests ordered accounted for 14% ( n = 21) of all interventions. Studies related to the management of anti-infective agents and blood formation, coagulation, and thrombosis agents consisted of the majority of the lab tests ordered; INR/PTT and vancomycin levels were the most commonly ordered. Thirteen percent ( n = 19) of all interventions include pain management adjustments with an even distribution between pain medications.

Several protocols were less frequently used, specifically the stress ulcer prophylaxis protocol (representing 3% of all interventions or n = 5), base solution changes (< 1% of all interventions or n = 1), and adjustment of administration time (7.6% of all interventions, n = 11). Of the time adjustments, more than 50% ( n = 6) involved furosemide.

Discussion

While the literature has many studies describing pharmacists improving outcomes through successful provision of clinical programs by protocol in the acute care hospital setting, the majority of studies are limited to single or focused protocols [2–24,27,37,38]. This approach fails to recognize or limits application of a pharmacist’s expertise in pharmacotherapy, as intervention is permitted only on defined agents under specific circumstances. This is the only report we are aware of that addresses a broader approach in permitting pharmacists to optimize pharmaco-therapy during the course of their usual practice through a single policy. As better outcomes are associated with allowing professionals to work to the fullest extent of their expertise, a broad range of protocols identified as pharmacy clinical services were selected and integrated into a singular policy that would be the foundation for instituting cultural change in regard to the elements considered to be routine pharmacy practice. Thus, the protocols applied here did not specify agents that could be adjusted for renal function or classes for which formulation conversion were permissible. This is also the case for dose formulation adjustments, where the protocol allowed for the pharmacist to apply their expertise beyond 1:1 conversions using standardized drug information references (Table 1 and Table 2). As such, the protocols allowed for the full application of the pharmacist’s expertise as a pharmacotherapy consultant within these intervention categories to assure that therapies are optimized. Additionally, eliminating phone calls streamlined the workflow for both the pharmacist and physicians, thus minimizing interruptions that distract from the other functions in which they are engaged.