Our navigators would make calls together with the patient to make a PCP appointment and would remind them of upcoming PCP appointments. In some cases, navigators would attend appointments with the patient; in addition, they would help advocate for them when they had to go to the emergency department. If a patient missed a PCP appointment, the navigator followed up to find out why and how to secure another appointment. Navigators would follow-up every 10 days if a patient had not yet seen a PCP. As many of our patients did not understand why they needed to have a PCP when they had a specialist, the navigators educated patients on the importance of PCP care.

In additon, navigators helped our patients deal with insurance coverage problems, such as frequent insurance changes/insurance getting dropped. Some patients had low literacy or had difficulties in filling out disability or insurance forms properly. Navigators received training from state coordinators for Medicaid and SSI disability on filling out the respective forms, which can be confusing.

Our navigators were trained in motivational interviewing and used it to identify other barriers patients were facing. In trying to obtain proper care, our patients struggled with competing priorities (eg, food, shelter, child care). Because of the numerous challenges that our patients and families face, an important role for the patients navigators was creating a bridge to accessing social and community resources.

Outcomes

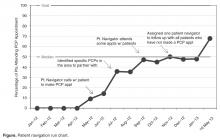

Of the 21 patients referred for help in obtaining a PCP, to date 13 (62%) attended an initial appointment with a new PCP ( Figure).The help and support provided by the navigators is helpful in mitigating the mistrust our patients have about the health care system, in part due to unfavorable initial experiences as young adults or being stereotyped for pain issues. Our patients have said that navigators make them feel like they have an advocate—someone who is on their side.

Subsequent to forming the initial navigator group, we expanded our program by adding 2 patient navigators in Colorado Springs, a smaller metropolitan area about an hour and a half south of Denver. In Colorado Springs, 16 referrals for services have been made but none of these referrals were specifically for a PCP, since access to a PCP was not a barrier to care in that locale. Patients were more likely to need help with things such as transportation to get to their location of specialty care.

Conclusion

Coordination of care is essential for individuals with chronic diseases. While the focus to date has been on coordination of care for common chronic illness such as diabetes, it is essential to use best practices for individuals with less common, but often more complex, chronic diseases such as SCD. To facilitate coordination of care for this population who receive specialty care in an academic medical center, we developed a patient navigation program for adults with SCD as a quality improvement project. Our navigation program assisted 62% of referred adults in the Denver metropolitan area in identifying a PCP and attending an initial appointment.