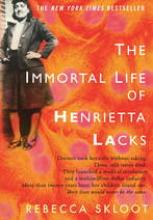

The story of how researchers transformed a cervical tumor from Henrietta Lacks into a ubiquitous lab tool, HeLa cells, without the knowledge or consent of Ms. Lacks or her family happened in what, for biomedical research, is ancient history, more than half a century ago. Rebecca Skloot’s book that chronicled that episode and its lengthy aftermath, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, first appeared less than 2 years ago, and the book seems to have had a noticeable impact on the public’s opinion of clinical-specimen collection and use.

Last month, I covered a workshop sponsored by the Drug Information Association that brought together about 100 people from around the world who deal with facilitating or regulating the collection of clinical specimens for genetic analyses to complement drug trials. Genetic studies of clinical samples have for years had to negotiate a tricky path through informed consent, confidentiality, and regulatory oversight, but according to a couple of speakers at the workshop who noted the Henrietta Lacks story during their talks, the 19 months since the book’s publication has made some people even more wary of this research.

“I think it was disconcerting to people who are not used to thinking about how specimens are handled, that their specimens could outlive them,” said the meeting’s main organizer and chair, Amelia Wall Warner, who heads clinical pharmacogenomics and clinical specimen management for the drug company Merck. The Skloot book “seems to be creating a lot of conversation, with patients often asking for a menu of consent. It seems like there is a movement to go back to tailored consent forms,” where each patient wants a personalized consent form based on their comfort level with various research options for their clinical specimens, something that large-scale trials with many thousands of patients can’t accommodate, Dr. Warner noted.

Rebecca Skloot’s book on Henrietta Lacks “has raised sensitivity” for many people about the potential ethical and confidentiality dangers of biomedical research “without a counterbalancing, responsible story being told about the benefits” of this research, said Barbara E. Bierer, a physician and senior vice president for research at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “We have not done a good job of telling people the public-health benefits of genetic and genomic research. The popularity of the book seems to have intensified” concerns about biomedical research. But, Bierer stressed, the key mistakes that researchers made when they created HeLa cells--the identification link to Henrietta Lacks and the fact that she and her family received no information about the work with her tissue-“could not happen today.”

The Drug Information Association workshop was concerned with tissues taken as specimens for specific, well-defined research projects, not tissue removed in routine medical procedures, as happened to Henrietta Lacks. Interestingly, Rebecca Skloot herself recently noted on her website that little has changed in the oversight and law regarding the latter type of specimens.

Skloot explored the many, sticky sides of research that uses tissue collected by biopsies, tumor removals, and blood tests in a 2006 article she wrote for The New York Times. As she notes in that article, scientists “are just using tissue scraps [patients] parted with voluntarily,” but when the cells themselves or the findings obtained from the cells lead to new reagents or tests worth millions of dollars issues of ownership and informed consent often follow.

According to Skloot’s comments on her website, what happened to Henrietta Lacks and the creation of HeLa cells could very well happen again; not linkage of the identify of the tissue donor to the end product, but creation of a widely used biomedical resource with no consent from or compensation to the person the tissue came from. And as Skloot’s 2006 article makes clear, whether or not that’s a problem remains uncertain, and it is something about which well-informed people have failed to reach a consensus.

--Mitchel Zoler (on Twitter @mitchelzoler)