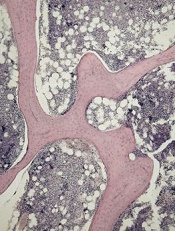

of cancellous bone

Patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) may experience significant bone loss much earlier than previously assumed, according to a study published in the journal Bone.

Investigators analyzed a cohort of adolescent and young adult ALL patients before and after their first month of chemotherapy and observed “significant alterations” to cancellous and cortical bone in this short period of time.

Previous studies to determine the changes to bone density during ALL therapy had focused on the cumulative effects of chemotherapy after months or even years of treatment.

“In clinic, we would see patients with fractures and vertebral compression during the very first few weeks of treatment,” said study author Etan Orgel, MD, of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles in California.

“But we were unaware of any study that specifically examined bone before chemotherapy and immediately after the first 30 days of treatment, which would allow us to understand the impact of this early treatment phase.”

So Dr Orgel and his colleagues conducted a prospective study of 38 patients, ages 10 to 21, who were newly diagnosed with ALL.

The team used quantitative computerized tomography (QCT) to assess leukemia-related changes to bone at diagnosis and then the subsequent effects of the induction phase of chemotherapy.

All of the patients received a 28-day induction regimen consisting of vincristine, pegylated L-asparaginase, anthracycline (daunorubicin or doxorubicin), and a glucocorticoid (either prednisone at 60 mg/m2/day for 28 days or dexamethasone at 10 mg/m2/day for 14 days).

The investigators compared the patients to age- and sex-matched controls and found that leukemia did not dramatically alter the properties of bone before chemotherapy.

However, QCT revealed significant changes during the 30-day induction phase in the 35 patients who were well enough to undergo imaging after treatment.

The patients experienced a significant decrease in cancellous volumetric bone mineral density, which was measured in the spine. The median decrease was 27% (P<0.001).

There was no significant change in cortical volumetric bone mineral density, which was measured in the tibia (−0.0%, P=0.860) or femur (−0.7%, P=0.290).

But there was significant cortical thinning in the tibia. The average cortical thickness decreased 1.2% (P<0.001), and the cortical area decreased 0.4% (P=0.014).

The femur was less affected, the investigators said. There was a decrease in average cortical thickness, but this was not significant (-0.3%, P=0.740).

To help clinicians relate to these findings, the investigators also measured bone mineral density using the older but more widely available technique of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. They found that it underestimated these changes as compared to QCT measurements.

“Now that we know how soon bone toxicity occurs, we need to re-evaluate our approaches to managing these changes and focus research efforts on new ways to mitigate this common yet significant adverse effect,” said study author Steven Mittelman, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.