APPROACH TO ADJUVANT CHEMOTHERAPY

Adjuvant chemotherapy seeks to eliminate micrometastatic disease present following curative surgical resection. When stage 0 cancer is discovered incidentally during colonoscopy, endoscopic resection alone is the management of choice, as presence of micrometastatic disease is exceedingly unlikely.26 Stage I–III CRCs are treated with surgical resection withcurative intent. The 5-year survival rate for stage I and early-stage II CRC is estimated at 97% with surgery alone.27,28 The survival rate drops to about 60% for high-risk stage II tumors (T4aN0), and down to 50% or less for stage II-T4N0 or stage III cancers. Adjuvant chemotherapy is generally recommended to further decrease the rates of distant recurrence in certain cases of stage II and in all stage III tumors.

DETERMINATION OF BENEFIT FROM CHEMOTHERAPY: PROGNOSTIC MARKERS

Prior to administration of adjuvant chemotherapy, a clinical evaluation by the medical oncologist to determine appropriateness and safety of treatment is paramount. Poor performance status and comorbid conditions may indicate risk for excessive toxicity and minimal benefit from chemotherapy. CRC commonly presents in older individuals, with the median age at diagnosis of 69 years for men and 73 years for women.29 In this patient population, comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and renal dysfunction are more prevalent.30 Decisions regarding adjuvant chemotherapy in this patient population have to take into consideration the fact that older patients may experience higher rates of toxicity with chemotherapy, including gastrointestinal toxicities and marrow suppression.31 Though some reports indicate patients older than 70 years derive similar benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy,32,33 a large pooled analysis of the ACCENT database, which included 7 adjuvant therapy trials and 14,528 patients, suggested limited benefit from the addition of oxaliplatin to fluorouracil in elderly patients.32 Other factors that weigh on the decision include stage, pathology, and presence of high-risk features. A common concern in the postoperative setting is delaying initiation of chemotherapy to allow adequate wound healing; however, evidence suggests that delays longer than 8 weeks leads to worse overall survival, with hazard ratios (HR) ranging from 1.4 to 1.7.34,35 Thus, the start of adjuvant therapy should ideally be within this time frame.

HIGH-RISK FEATURES

Multiple factors have been found to predict worse outcome and are classified as high-risk features (Table 2). Histologically, high-grade or poorly differentiated tumors are associated with higher recurrence rate and worse outcome.36 Certain histological subtypes, including mucinous and signet-ring, both appear to have more aggressive biology.37 Presence of microscopic invasion into surrounding blood vessels (vascular invasion) and nerves (perineural invasion) is associated with lower survival.38 Penetration of the cancer through the visceral peritoneum (T4a) or into surrounding structures (T4b) is associated with lower survival.36 During surgical resection, multiple lymph nodes are removed along with the primary tumor to evaluate for metastasis to the regional nodes. Multiple analyses have demonstrated that removal and pathologic assessment of fewer than 12 lymph nodes is associated with high risk of missing a positive node, and is thus equated with high risk.39–41 In addition, extension of tumor beyond the capsules of any single lymph node, termed extracapsular extension, is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality.42 Tumor deposits, or focal aggregates of adenocarcinoma in the pericolic fat that are not contiguous with the primary tumor and are not associated with lymph nodes, are currently classified as lymph nodes as N1c in the current TNM staging system. Presence of these deposits has been found to predict poor outcome stage for stage.43 Obstruction and/or perforation secondary to the tumor are also considered high-risk features that predict poor outcome.

SIDEDNESS

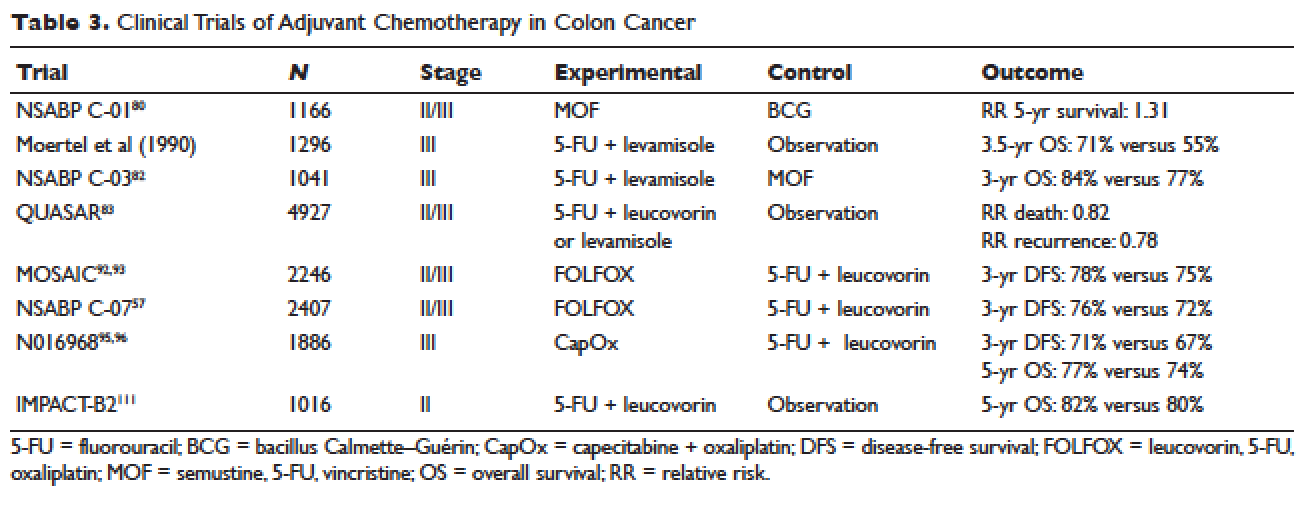

As reported at the 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting, tumor location predicts outcome in the metastatic setting. A report by Venook and colleagues based on a post-hoc analysis found that in the metastatic setting, location of the tumor primary in the left side is associated with longer OS (33.3 months) when compared to the right side of the colon (19.4 months).44 A retrospective analysis of multiple databases presented by Schrag and colleagues similarly reported inferior outcomes in patients with stage III and IV disease who had right-sided primary tumors.45 However, the prognostic implications for stage II disease remain uncertain.

BIOMARKERS

Given the controversy regarding adjuvant therapy of patients with stage II colon cancer, multiple biomarkers have been evaluated as possible predictive markers that can assist in this decision. The mismatch repair (MMR) system is a complex cellular enzymatic mechanism that identifies and corrects DNA errors during cell division and prevents mutagenesis.46 The familial cancer syndrome HNPCC is linked to alteration in a variety of MMR genes, leading to deficient mismatch repair (dMMR), also termed microsatellite instability-high (MSI-high).47,48 Epigenetic modification can also lead to silencing of the same implicated genes and accounts for 15% to 20% of sporadic colorectal cancer.49 These epigenetic modifications lead to hypermethylation of the promotor region of MLH1 in 70% of cases.50 The 4 MMR genes most commonly tested are MLH-1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2. Testing can be performed by immunohistochemistry or polymerase chain reaction.51 Across tumor histology and stage, MSI status is prognostic. Patients with MSI-high tumors have been shown to have improved prognosis and longer OS both in stage II and III disease52–54 and in the metastatic setting.55 However, despite this survival benefit, there is conflicting data as to whether patients with stage II, MSI-high colon cancer may benefit less from adjuvant chemotherapy. One early retrospective study compared outcomes of 70 patients with stage II and III disease and dMMR to those of 387 patients with stage II and III disease and proficient mismatch repair (pMMR). Adjuvant fluorouracil with leucovorin improved DFS for patients with pMMR (HR 0.67) but not for those with dMMR (HR 1.10). In addition, for patients with stage II disease and dMMR, the HR for OS was inferior at 2.95.56 Data collected from randomized clinical trials using fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy were analyzed in an attempt to predict benefit based on MSI status. Benefit was only seen in pMMR patients, with a HR of 0.72; this was not seen in the dMMR patients.57 Subsequent studies have had different findings and did not demonstrate a detrimental effect of fluorouracil in dMMR.58,59 For stage III patients, MSI status does not appear to affect benefit from chemotherapy, as analysis of data from the NSABP C-07 trial (Table 3) demonstrated benefit of FOLFOX (leucovorin, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin) in patients with dMMR status and stage III disease.59

Another genetic abnormality identified in colon cancers is chromosome 18q loss of heterozygosity (LOH). The presence of 18q LOH appears to be inversely associated with MSI-high status. Some reports have linked presence of 18q with worse outcome,60 but others question this, arguing the finding may simply be related to MSI status.61,62 This biomarker has not been established as a clear prognostic marker that can aid clinical decisions.