Academic Medical Centers (AMCs) have been given unique responsibilities to care for patients, educate future clinicians, and bring innovative research to the bedside. Over the last few decades, this tripartite mission has served the United States well, and payers (Federal, State, and commercial) have been willing to underwrite these missions with overt and covert financial subsidies. As cost containment efforts have escalated, the traditional business model of AMCs has been challenged. In this issue, Dr Anil Rustgi and I offer some insights into how AMCs must alter their business model to be sustainable in our new world of accountable care, cost containment, and clinical integration.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF, Special Section Editor

Academic medicine, including academic gastrointestinal (GI) medicine, has been founded and has flourished on the tripartite missions of research, teaching/education, and patient care. Academic medical centers (AMCs) have unique and historical responsibilities to translate research discoveries into innovative patient care and train the next generation of physicians in both medical sciences and health care delivery. In this era of fiscal constraint, there are current and anticipated challenges, which are triggered by reductions in the National Institutes of Health budget, implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), federal budget constraints ("Sequestration"), and the increasingly complex relationship between health care systems, insurance companies, regulatory entities, the pharmaceutical industry, and medical device companies. In direct and indirect fashions, these events will force leaders of academic GI divisions to reexamine the business infrastructures of their division\'s clinical practice. Such plasticity and adaptation will serve to invigorate academic medicine and its multifaceted roles. The financial and clinical pressures emerging as a result of the current wave of health care reform have been defined in previous articles within this section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, including descriptions of the "Roadmap to the Future of GI Practice,"1 general descriptions of health care reform,2,3 and specific pressures on AMCs.4

Sources of revenue for academic gastrointestinal divisions

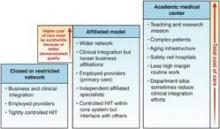

Figure 1. Hospital-based integrated delivery networks (IDNs). A closed or restricted network (far left) is composed of fully employed providers, a single enterprise-wide EMR, and tight business and clinical integration. An affiliated model (middle) is composed of a health system that owns hospitals and other delivery sites (e.g., transitional care units or skilled nursing facilities) plus some providers (usually primary care); independent specialists are affiliated closely but may not be fully employed. Academic medical centers (far right) have additional costs (teaching and education) but are under the same pressures to demonstrate their added value. The height of each column represents total cost of care paid by payers. HIT, health integration team.

Changes to the business model of academic GI divisions must remain consistent with the deep-rooted tripartite commitments of AMCs. One of the greatest challenges facing many division chiefs today is to remain true to research and teaching missions when their sources of revenue becomes increasingly dependent on clinical productivity. Currently, sources of revenue for a GI division include research grant support, philanthropy, partnerships with industry, and clinical revenue. In many AMCs, clinical revenue now exceeds all other sources of funding, a fact that underscores the importance of building a robust and sustainable clinical enterprise.

Research revenue

Research grant support emanates traditionally from the National Institutes of Health, but there are other sources as well, including but not restricted to federal agencies (eg, Department of Defense, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Centers for Disease Control, among others), national specialty societies (eg, American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American Society of GI Endoscopy, American College of Gastroenterology), and private foundations (eg, Crohn\'s and Colitis Foundation of America). Grant support tends to target different stages of career: trainees, those making the transition from a mentored phase to an independent phase, and established investigators.

Philanthropy and industry partnerships

Academic GI divisions rely on contributions from philanthropy and partnerships with industry, but these are not fixed amounts in a predictable fashion. Depending on the amount of philanthropy, donations may result in endowments that are interest-bearing (eg, endowed chairs for faculty or for research/education) or gift accounts ("spend as you go"). Partnerships with industry, both pharmaceutical and medical device, have been and remain an important source of support for research, education, and training. New regulations within the PPACA have altered these relationships substantially. The Physician Payment Sunshine Act, Section 6002 of PPACA, was created to provide transparency in physicians\' interactions with medical device, pharmaceutical, and biological industries. As of August 1, 2013, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid requires drug and device manufacturers to track (at a provider level) payments and other transfers of value exceeding $10 (single instance) or $100 (aggregate during 1 year) provided to physicians and teaching hospitals, with payments posted on a public Web site. This topic is beyond the scope of this article but is an important area that should be understood by all gastroenterologists.5