Content from this column was originally published in the "Practice Management: The Road Ahead" section of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (Source: Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;10:472-4). "Practice Management Toolbox" provides key information and resources necessary for facing the unique challenges of today’s clinical practices.

Resources for Practical Application

To view additional online resources about this topic and to access our Coding Corner, visit www.cghjournal.org/content/practice_management.

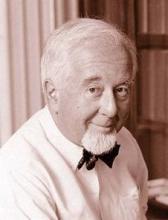

In Memoriam

Dr. Howard Spiro passed away on March 11, 2012. He was the founding chief of the Gastroenterology Section at Yale University, a position he held from 1955 to 1982. During that time, he became widely known for his clinical acumen as well as his teaching style, abilities, and innovations. He was also a prolific writer; in addition to publishing numerous scientific manuscripts, he authored several books and was the founding editor of Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. For these and related contributions, the American Gastroenterological Association awarded him with the Julius Friedenwald Medal in 2000. After stepping down as section chief, Dr. Spiro founded the Yale Program for Humanities and Medicine, which provided a forum for examining the boundaries between medicine and the humanities and exploration of "the culture of medicine, medical care, and experiences of illness." He remained active in this program until his passing. Therefore, it is appropriate that this, perhaps his final manuscript, bridges his two loves by discussing humanistic considerations in the doctor-patient relationship for an audience of gastroenterologists.

Michael H. Nathanson, M.D., Ph.D.

Professor of Medicine and Cell Biology

Director, Yale Liver Center

Chief, Section of Digestive Diseases

Yale University School of Medicine

New Haven, Connecticut

In 1947, when I graduated from medical school, so little was known about the inside of a cell that diagrams showed the nucleus floating in a barren cytoplasmic sea. In 2012, a similar diagram would mimic the Sargasso Sea, packed with seaweed connections.

Neuroscience has enormously clarified how the brain works, even though the mind and consciousness still escape explanation. Connections between hormones and neurotransmitters in the brain are so duplicated in the gut that some gastroenterologists have called our favorite organ "the second brain." Whether that makes the dejecta cousin to thought, I dare not contemplate.

At a Yale gastrointestinal conference a while back, there was joy at the new endoscopes looking beyond the mucosa into the very cells, someday to record broken cytokines or maybe to mend a limping lysosome. Happy at seeing what had been so hidden, I was sad to think how far knowledge of the brain has surpassed comprehension of the mind.

That gap between brain and mind might be what makes study of science so different from contemplation of the humanities. It bears on the difference between reason and intuition. What Plato wrote about life and death remains as pertinent as last week’s New England Journal of Medicine. Ideas from Athens and Jerusalem still today pervade our thinking and our purpose and into that trove, happily, pour the vast cultures of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa.

In the hubris of success, medical researchers look back only a very few years, maybe to 2001, but when we talk about falling sick or growing old, what Cicero, in his exile far from Rome, or Virginia Woolf, hiding in London, wrote remains as pertinent as yesterday’s New York Times. Sophocles’ drama of Philoctetes abandoned on an island with his stinking leg helps doctors to share the loneliness of the sick; Kafka’s "Metamorphosis" lets us feel the torment of our body’s betrayal.

The clergy are more generous to the past. When a study showed that red wine killed Helicobacter pylori, a Yale Divinity School professor boasted to me that was why St. Paul advised, "Take a little wine for the sake of thy stomach." "You see," my friend exulted, "that St. Paul really knew what he was talking about!"

Long-dead observers and thinkers remain as pertinent to human society as ever. Freud reminded us of the subconscious; modern theories about mind are influential even when we do not know their microscopic connections.

Reason rules the roost; current physicians are trained to think of the body as a machine to be repaired, people as collection of organs, and the mind as a secretion of the brain. Clinical practice has become a matter of following evidence, paradigms, and pathways. Interchange between patient and physician has shrunk to a series of questions and answers, pickled in electronic medical records.

Patients have disappeared into their functions, at least as far as the proverbial "laptop doc" is concerned. In current practice, what is displayed on images or by numbers dominates diagnosis, which leads to treating abnormalities that might not contribute to the patients’ troubles. Gastrointestinal fellows reach for an endoscope in the uninsured, to whom they have hardly listened. Yet technologic advances have much strengthened clinical practice. Echocardiography displays sounds so precisely that even a doctor who is deaf can become a cardiologist.