Role of cannabis in CVS

The role of cannabis in the pathogenesis of symptoms in CVS is controversial. While cannabis has antiemetic properties, there is a strong link between its use and CVS. The use of cannabis has increased over the past decade with increasing legalization.21 Several studies have shown that 40%-80% of patients with CVS use cannabis.22,23 Following this, cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) was coined as a separate entity based on this statistical association, though there are no data to support the notion that cannabis causes vomiting.24,25 CHS has clinical features that are indistinguishable from CVS except for the chronic heavy cannabis use. A peculiar bathing behavior called “compulsive hot-water bathing” has been described and was thought to be pathognomonic of cannabis use.26 During an episode, patients will take multiple hot showers/baths, which temporarily alleviate their symptoms. Many patients even report running out of hot water and sometimes check into a hotel for a continuous supply of hot water. A small number of patients may sustain burns from the hot-water bathing. However, studies show that this hot-water bathing behavior also is seen in about 50% of patents with CVS who do not use cannabis.22

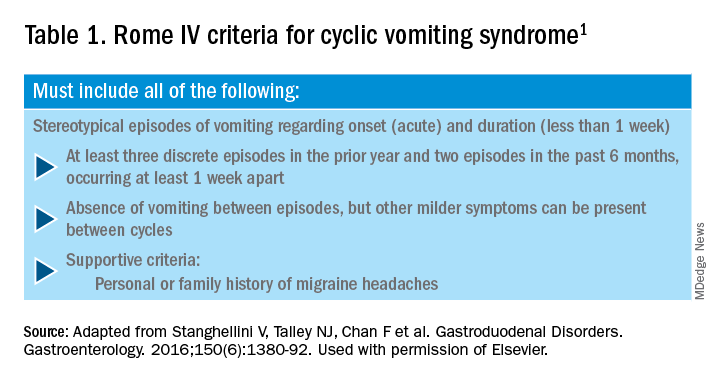

CHS is now defined by Rome IV criteria, which include episodes of nausea and vomiting similar to CVS preceded by chronic, heavy cannabis use. Patients must have complete resolution of symptoms following cessation.1 A recent systematic review of 376 cases of purported CHS showed that only 59 (15.7%) met Rome IV criteria for this disorder.27 This is because of considerable heterogeneity in how the diagnosis of CHS was made and the lack of standard diagnostic criteria at the time. Some cases of CHS were diagnosed merely based on an association of vomiting, hot-water bathing, and cannabis use.28 Only a minority of patients (71,19%) had a duration of follow-up more than 4 weeks, which would make it impossible to establish a diagnosis of CHS. A period of at least a year or a duration of time that spans at least three episodes is generally recommended to determine if abstinence from cannabis causes a true resolution of symptoms.27 Whether CHS is a separate entity or a subtype of CVS remains to be determined. The paradoxical effects of cannabis may happen because of the use of highly potent cannabis products that are currently in use. A complete discussion of the role of cannabis in CVS is beyond the scope of this article, and the reader is referred to a recent systematic review and discussion.27

Treatment

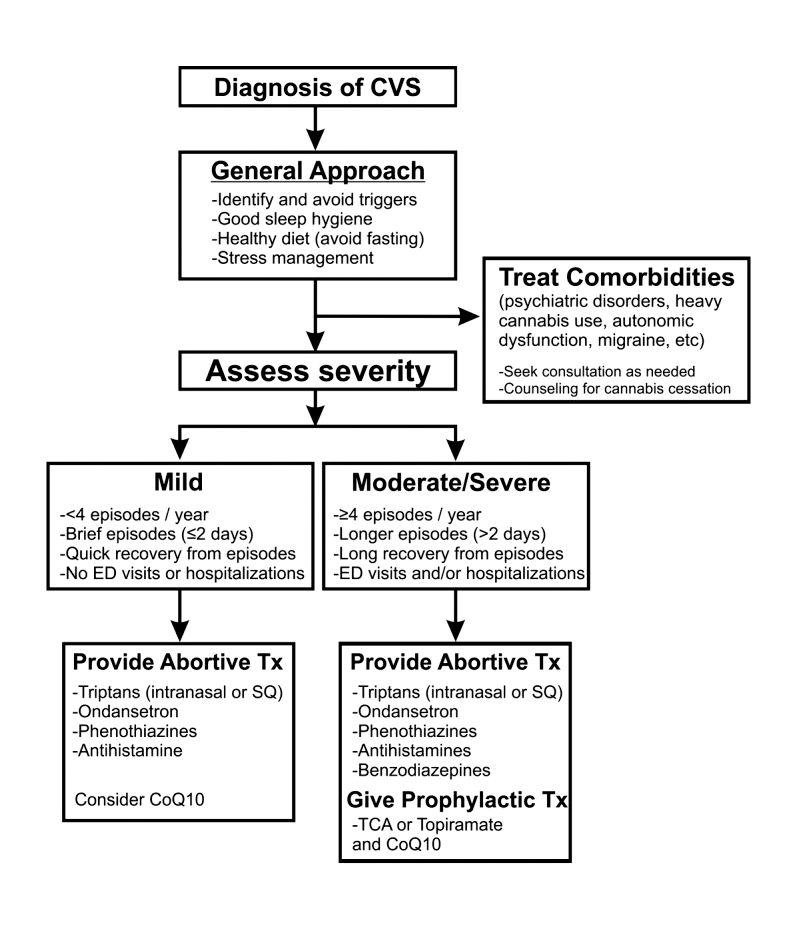

CVS should be treated based on a biopsychosocial model with a multidisciplinary team that includes a gastroenterologist with knowledge of CVS, primary care physician, psychologist, psychiatrist, and sleep specialist if needed.16 Initiating prophylactic treatment is based on the severity of disease. An algorithm for the treatment of CVS based on severity of symptoms is shown below.

Figure 2. Adapted and reprinted by permission from the Licensor: Springer Nature, Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology, Bhandari S, Venkatesan T. Novel Treatments for Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome: Beyond Ondansetron and Amitriptyline, 14:495-506, Copyright 2016.

Patients who have mild disease (defined as fewer than four episodes/year, episodes lasting up to 2 days, quick recovery from episodes, or episodes not requiring ED care or hospitalization) are usually prescribed abortive medications.16 These medications are best administered during the prodromal phase and can prevent progression to the emetic phase. Medications used for aborting episodes include sumatriptan (20 mg intranasal or 6 mg subcutaneous), ondansetron (8 mg sublingual), and diphenhydramine (25-50 mg).30,31 This combination can help abort symptoms and potentially avoid ED visits or hospitalizations. Patients with moderate-to-severe CVS are offered prophylactic therapy in addition to abortive therapy.16

Recent guidelines recommend tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) as the first-line agent in the prophylaxis of CVS episodes. Data from 14 studies determined that 70% (413/600) of patients responded partially or completely to TCAs.16 An open-label study of 46 patients by Hejazi et al. noted a decline in the number of CVS episodes from 17 to 3, in the duration of a CVS episode from 6 to 2 days, and in the number of ED visits/ hospitalizations from 15 to 3.3.32Amitriptyline should be started at 25 mg at night and titrated up by 10-25 mg each week to minimize emergence of side effects. The mean effective dose is 75-100 mg or 1.0-1.5 mg/kg. An EKG should be checked at baseline and during titration to monitor the QT interval. Unfortunately, side effects from TCAs are quite common and include cognitive impairment, drowsiness, dryness of mouth, weight gain, constipation, and mood changes, which may warrant dose reduction or discontinuation. Antiepileptics such as topiramate, mitochondrial supplements such as Coenzyme Q10 and riboflavin are alternative prophylactic agents in CVS.33 Aprepitant, a newer NK1 receptor antagonist has been found to be effective in refractory CVS.34 In addition to pharmacotherapy, addressing comorbid conditions such as anxiety and depression and counseling patients to abstain from heavy cannabis use is also important to achieve good health care outcomes.

In summary, CVS is a common, chronic functional GI disorder with episodic nausea, vomiting, and often, abdominal pain. Symptoms can be disabling, and prompt diagnosis and therapy is important. CVS is associated with multiple comorbid conditions such as migraine, anxiety and depression, and a biopsychosocial model of care is essential. Medications such as amitriptyline are effective in the prophylaxis of CVS, but side effects hamper their use. Recent recommendations for management of CVS have been published.16 Cannabis is frequently used by patients for symptom relief but use of high potency products may cause worsening of symptoms or unmask symptoms in genetically predisposed individuals.23 Studies to elucidate the pathophysiology of CVS should help in the development of better therapies.

Dr. Mooers is PGY-2, an internal medicine resident in the department of medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee; Dr. Venkatesan is professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

1. Stanghellini V et al. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1380-92.

2. Aziz I et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Apr;17(5):878-86.

3. Kovacic K et al. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2018;20(10):46.

4. Zaki EA et al. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:719-28.

5. Venkatesan T et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:181.

6. Ellingsen DM et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29 (6)e13004 9.

7. Venkatesan T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:1409-18.

8. Wasilewski A et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:933-9.

9. van Sickle MD et al. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2003;285:G566-76.

10. Parker LA et al. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:1411-22.

11. van Sickle MD et al. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:767-74.

12. Fleisher DR et al. BMC Med. 2005;3:20.

13. Kumar N et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:52.

14. Li BU et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:379-93.

15. Bhandari S et al. Clin Auton Res. 2018 Apr;28(2):203-9.

16. Venkatesan T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31 Suppl 2:e13604. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13604.

17. Sagar RC et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13174.

18. Taranukha T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018 Apr;30(4):e13245. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13245.

19. Bhandari S and Venkatesan T. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:2035-44.

20. Choung RS et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24:20-6, e21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01791.x.

21. Bhandari S et al. Intern Med J. 2019 May;49(5):649-55.

22. Venkatesan T et al. Exp Brain Res. 2014; 232:2563-70.

23. Venkatesan T et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jul 25. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.039.

24. Simonetto DA et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:114-9.

25. Wallace EA et al. South Med J. 2011;104:659-64.

26. Allen JH et al. Gut. 2004;53:1566-70.

27. Venkatesan T et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31 Suppl 2:e13606. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13606.

28. Habboushe J et al. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2018;122:660-2.

29. Bhandari S and Venkatesan T. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2016;14:495-506.

30. Hikita T et al. Cephalalgia. 2011;31:504-7.

31. Fuseau E et al. Clin Pharmacokinet 2002;41:801-11.

32. Hejazi RA et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:18-21.

33. Sezer OB and Sezer T. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;22:656-60.

34. Cristofori F et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:309-17.