Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third-most common cancer worldwide and accounts for almost 11% of all cancer diagnoses, with > 1.9 million cases reported globally.1,2 CRC is the second-most deadly cancer, responsible for about 935,000 deaths.1 Over the past several decades, a steady decline in CRC incidence and mortality has been reported in developed countries, including the US.3,4 From 2008 through 2017, an annual reduction of 3% in CRC death rates was reported in individuals aged ≥ 65 years.5 This decline can mainly be attributed to improvements made in health systems and advancements in CRC screening programs.3,5

US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends CRC screening in individuals aged 45 to 75 years. USPSTF recommends direct visualization tests, such as colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy for CRC screening.6 Although colonoscopy is commonly used for CRC screening, it is an invasive procedure that requires bowel preparation and sedation, and has the potential risk of colonic perforation, bleeding, and infection. Additionally, social determinants—such as health care costs, missed work, and geographic location (eg, rural communities)—may limit colonoscopy utilization.7 As a result, other cost-effective, noninvasive tests such as high-sensitivity guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) and fecal immunochemical test (FIT) are also used for CRC screening. These tests detect occult blood in the stool of individuals who may be at risk for CRC, helping direct them to colonoscopy if they screen positive.8

The gFOBT relies on simple oxidation and requires a stool sample to detect the presence of the heme component of blood.9 If heme is present in the stool sample, it will enable the oxidation of guaiac to form a blue-colored dye when added to hydrogen peroxide. It is important to note that the oxidation component of this test may lead to false-positive results, as it may detect dietary hemoglobin present in red meat. Medications or foods that have peroxidase properties may also result in a false-positive gFOBT result. Additionally, false-negative results may be caused by antioxidants, which may interfere with the oxidation of guaiac.

FIT uses antibodies, which bind to the intact globin component of human hemoglobin.9 The quantity of bound antibody-hemoglobin complex is detected and measured by a variety of automated quantitative techniques. This testing strategy eliminates the need for food or medication restrictions and the subjective visual assessment of change in color, as required for the gFOBT.9 A 2016 meta-analysis found that FIT performed better compared with gFOBT in terms of specificity, positivity rate, number needed to scope, and number needed to screen.8 The FIT screening method has also been found to have greater adherence rates, which is likely due to fewer stool sampling requirements and the lack of medication or dietary restrictions, compared with gFOBT.7,8

The COVID-19 pandemic had a drastic impact on CRC preventive care services. In March 2020, elective colonoscopies were temporarily ceased across the country and the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) deferred all elective surgeries and medical procedures, including screening and surveillance colonoscopies. In line with these recommendations, elective colonoscopies were temporarily ceased across the country.10 The National Cancer Institute’s Population-Based Research to Optimize the Screening Process consortium reported that CRC screening rates decreased by 82% across the US in 2020.11 Public health measures are likely the main reason for this decline, but other factors may include a lack of resource availability in outpatient settings and public fear of the pandemic.10

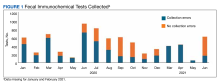

The James A. Haley Veterans Affairs Hospital (JAHVAH) in Tampa, Florida, encouraged the use of FIT in place of colonoscopies to avoid delaying preventive services. The initiative to continue CRC screening methods via FIT was scrutinized when laboratory personnel reported that in fiscal year (FY) 2020, 62% of the FIT kits that patients returned to the laboratory were missing information or had other errors (Figure 1). These improperly returned FIT kits led to delayed processing, canceled orders, increased staff workload, and more costs for FIT repetition.

Research shows many patients often fail to adhere to the instructions for proper FIT sample collection and return. Wang and colleagues reported that of 4916 FIT samples returned to the laboratory, 971 (20%) had collection errors, and 910 (94%) of those samples were missing a sample collection date.12 The sample collection date is important because hemoglobin degradation occurs over time, which may create false-negative FIT results. Although studies have found that sample return times of ≤ 10 days are not associated with a decrease in FIT positive rates, it is recommended to mail completed FITs within 24 hours of sample collection.13

Because remote screening methods like FIT were preferred during the COVID-19 pandemic, we conducted a quality improvement (QI) project to address FIT inefficiency. The aim of this initiative was to determine the root cause behind incorrectly returned FIT kits and to increase correctly collected and testable FIT kits upon initial laboratory arrival by at least 20% by the second quarter of FY 2021.