The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is understaffed for clinical psychologists who have specialty training in geriatrics (ie, geropsychologists) to meet the needs of aging veterans. Though only 16.8% of US adults are aged ≥ 65 years,1 this age group comprises 45.9% of patients within the VHA.2 The needs of older adults are complex and warrant specialized services from mental health clinicians trained to understand lifespan developmental processes, biological changes associated with aging, and changes in psychosocial functioning.

Older veterans (aged ≥ 65 years) present with higher rates of combined medical and mental health diagnoses compared to both younger veterans and older adults who are not veterans.3 Nearly 1 of 5 (18.1%) older veterans who use VHA services have confirmed mental health diagnoses, and an additional 25.5% have documented mental health concerns without a formal diagnosis in their health record.4 The clinical presentations of older veterans frequently differ from younger adults and include greater complexity. For example, older veterans face an increased risk of cognitive impairment compared to the general population, due in part to higher prevalence of posttraumatic stress, which doubles their risk of developing dementia.5 Additional examples of multicomplexity among older veterans may include co-occurring medical and psychiatric diagnoses, the presence of delirium, social isolation/loneliness, and concerns related to polypharmacy. These complex presentations result in significant challenges for mental health clinicians in areas like assessment (eg, accuracy of case conceptualization), intervention (eg, selection and prioritization), and consultation (eg, coordination among multiple medical and mental health specialists).

Older veterans also present with substantial resilience. Research has found that aging veterans exposed to trauma during their military service often review their memories and past experiences, which is known as later-adulthood trauma reengagement.6 Through this normative life review process, veterans engage with memories and experiences from their past that they previously avoided, which could lead to posttraumatic growth for some. Unfortunately, others may experience an increase in psychological distress. Mental health clinicians with specialty expertise and training in aging and lifespan development can facilitate positive outcomes to reduce distress.7

The United States in general, and the VHA specifically, face a growing shortage of geriatric mental health clinicians. In a 2015 American Psychological Association survey, 1528 of 4109 respondents (37.2%) reported they frequently or very frequently administered care to older adults, yet only 49 respondents (1.2%) reported geropsychology as their specialty.8 According to the National Provider Registry, 660 clinicians self-identified as geropsychologists (ie, those who self-reported “psychologist: adult development and aging” as an NPI Healthcare Provider taxonomy code) in the US, representing < 1% of all doctoral level psychologists.9 The number of psychologists who obtain board certification from the American Board of Geropsychology is even lower (only 112 clinicians as of February 2024).10 Many psychologists within the VHA treat older veterans in integrated health settings such as primary care, home-based primary care, community living centers, or behavioral health care, but many lack formal training in geropsychology.

The Geriatric Scholars Program (GSP) was developed in 2008 to address the training gap and provide education in geriatrics to VHA clinicians that treat older veterans, particularly in rural areas.11,12 The GSP initially focused on primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists. It was later expanded to include other disciplines (ie, social work, rehabilitation therapists, and psychiatrists). In 2013, the GSP – Psychology Track (GSP-P) was developed with funding from the VHA Offices of Rural Health and Geriatrics and Extended Care specifically for psychologists.

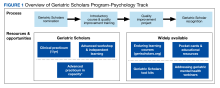

This article describes the multicomponent longitudinal GSP-P, which has evolved to meet the target audience’s ongoing needs for knowledge, skills, and opportunities to refine practice behaviors. GSP-P received the 2020 Award for Excellence in Geropsychology Training from the Council of Professional Geropsychology Training Programs. GSP-P has grown within the context of the larger GSP and aligns with the other existing elective learning opportunities (Figure 1).