Results

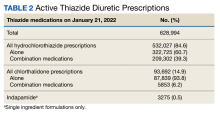

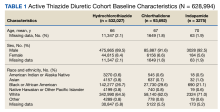

As of January 21, 2022, the active thiazide cohort yielded 628,994 thiazide prescriptions within the VA nationwide. Most patients were male, with female patients representing 8.4%, 6.6%, and 5.6% of the HCTZ, chlorthalidone, and indapamide arms, respectively (Table 1). Utilization rates were significantly different between thiazide groups (P < .001). HCTZ was the most prescribed thiazide diuretic (84.6%) followed by chlorthalidone (14.9%) and indapamide (0.5%) (Table 2).

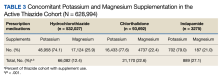

BP values documented after prescription initiation date were available for few individuals in the HCTZ, chlorthalidone, and indapamide groups (0.3%, 0.2%, and 0.5%, respectively). Overall, the mean BP values were similar among thiazide groups: 135/79 mm Hg for HCTZ, 137/78 mm Hg for chlorthalidone, and 133/79 mm Hg for indapamide (P = .32). BP control was also similar with control rates of 26.0%, 27.1%, and 33.3% for those on HCTZ, chlorthalidone, and indapamide, respectively (P = .75). The use of concomitant potassium or magnesium supplementation was significantly different between thiazide groups with rates of 12.4%, 22.6%, and 27.1% for HCTZ, chlorthalidone, and indapamide, respectively (P < .001). When comparing chlorthalidone to HCTZ, there was a significantly higher rate of concomitant supplementation with chlorthalidone (P < .001) (Table 3).

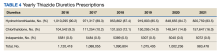

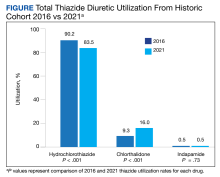

In the historic cohort, HCTZ utilization decreased from 90.2% to 83.5% (P < .001) and chlorthalidone utilization increased significantly from 9.3% to 16.0% (P < .001) (Figure). There was no significant change in the use of indapamide during this period (P = .73). Yearly trends from 2016 to 2021 are listed in Table 4.

Discussion

The findings of our evaluation demonstrate that despite the 2017 ACC/AHA BP guideline recommendations for using chlorthalidone, HCTZ predominates as the most prescribed thiazide diuretic within the VA. However, since the publication of this guideline, there has been an increase in chlorthalidone prescribing and a decrease in HCTZ prescribing within the VA.

A 2010 study by Ernst and colleagues revealed a similar trend to what was seen in our study. At that time, HCTZ was the most prescribed thiazide encompassing 95% of total thiazide utilization; however, chlorthalidone utilization increased from 1.1% in 2003 to 2.4% in 2008.8 In comparing our chlorthalidone utilization rates with these results, 9.3% in 2016 and 16.0% in 2021, the change in chlorthalidone prescribing from 2003 to 2016 represents a more than linear increase. This trend continued in our study from 2016 to 2021; the expected chlorthalidone utilization would be 21.2% in 2021 if it followed the 2003 to 2016 rate of change. Thus the trend in increasing chlorthalidone use predated the 2017 guideline recommendation. Nonetheless, this change in the thiazide prescribing pattern represents a positive shift in practice.

Our evaluation found a significantly higher rate of concomitant potassium or magnesium supplementation with chlorthalidone and indapamide compared with HCTZ in the active cohort. Electrolyte abnormalities are well documented adverse effects associated with thiazide diuretic use.9 A cross-sectional analysis by Ravioli and colleagues revealed thiazide diuretic use was an independent predictor of both hyponatremia (22.1% incidence) and hypokalemia (19% incidence) and that chlorthalidone was associated with the highest risk of electrolyte abnormalities whereas HCTZ was associated with the lowest risk. Their study also found these electrolyte abnormalities to have a dose-dependent relationship with the thiazide diuretic prescribed.10

While Ravioli and colleagues did not address the incidence of hypomagnesemia with thiazide diuretic use, a cross-sectional analysis by Kieboom and colleagues reported a significant increase in hypomagnesemia in patients prescribed thiazide diuretics.11 Although rates of electrolyte abnormalities are reported in the literature, the rates of concomitant supplementation are unclear, especially when compared across thiazide agents. Our study provides insight into the use of concomitant potassium and magnesium supplementation compared between HCTZ, chlorthalidone, and indapamide. In our active cohort, potassium was more commonly prescribed than magnesium. Interestingly, magnesium supplementation accounted for 25.9% of the total supplement use for HCTZ compared with rates of 22.4% and 21.0% for chlorthalidone and indapamide, respectively. It is unclear if this trend highlights a greater incidence of hypomagnesemia with HCTZ or greater clinician awareness to monitor this agent, but this finding may warrant further investigation. In addition, when considering the overall lower rate of supplementation seen with HCTZ in our study, the use of potassium-sparing diuretics should be considered. These agents, including triamterene, amiloride, eplerenone, and spironolactone, can be supplement-sparing and are available in combination products only with HCTZ.

Low chlorthalidone utilization rates are concerning especially given the literature demonstrating CVD benefit with chlorthalidone and the lack of compelling outcomes data to support HCTZ as the preferred agent.3,4 There are several reasons why HCTZ use may be higher in practice. First is clinical inertia, which is defined as a lack of treatment intensification or lack of changing practice patterns, despite evidence-based goals of care.12 HCTZ has been the most widely prescribed thiazide diuretic for years.7 As a result, converting HCTZ to chlorthalidone for a patient with suboptimal BP control may not be considered and instead clinicians may add on another antihypertensive or titrate doses of current antihypertensives.

There is also a consideration for patient adherence. HCTZ has many more combination products available than chlorthalidone and indapamide. If switching a patient from an HCTZ-containing combination product to chlorthalidone, adherence and patient willingness to take another capsule or tablet must be considered. Finally, there may be clinical controversy and questions around switching patients from HCTZ to chlorthalidone. Although the guidelines do not explicitly recommend switching to chlorthalidone, it may be reasonable in most patients unless they have or are at significant risk of electrolyte or metabolic disturbances that may be exacerbated or triggered with conversion.

When converting from HCTZ to chlorthalidone, it is important to consider dosing. Previous studies have demonstrated that chlorthalidone is 1.5 to 2 times more potent than HCTZ.13,14 Therefore, the conversion from HCTZ to chlorthalidone is not 1:1, but instead 50 mg of HCTZ is approximately equal to25 to 37.5 mg of chlorthalidone.14