Pathology

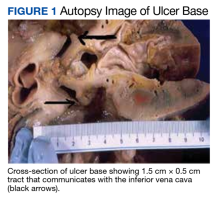

A full autopsy was performed 22 hours after the patient died. The lungs were congested and of increased weight: The right lung was 800 g, and the left was 750 g. The right lower lobe had a wedge-shaped infarction measuring 6 cm × 5 cm fed by a thrombosed vessel. Multiple small hemorrhagic wedge-shaped areas were noted in the left lung. An ulcer measuring 6 cm × 5 cm was noted just distal to the pylorus. At the base of this ulcer was a 1.5 cm × 0.5 cm tract that communicated with the inferior vena cava (Figure 1).

Extensive scarring was also noted around the area of the fistula extending into the superior portion of the right kidney. Distal to the ulcer, the bowel contents were blackish red to bloody through to and including the large intestine.A postmortem blood culture was positive for Clostridium perfringens (C perfringens) and Candida albicans (C Albicans). Interestingly, one of the collected blood culture vials exploded en route to the laboratory, presumably due to the presence of many gas-forming C perfringens bacteria.

On microscopic examination of the autopsy samples, gram-positive rods were observed in the tissue of multiple organs, including the heart, lungs, liver, and kidneys (Figure 2).

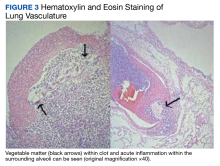

The base of the duodenal ulcer contained fungal forms consistent with C albicans. Examination of the lung vasculature was notable for multiple acute thrombi with foreign bodies within the clot, consistent with vegetable matter (Figure 3). The tissue around the thrombi showed evidence of an acute inflammatory response extending into the lung parenchyma.Serology

Fourteen days after the patient’s death, both PRBC units infused during transfusion reactions were positive for granulocyte antibodies by immunofluorescence and agglutination techniques. Human leukocyte antigen antibody testing was also sent but was not found in either the donor or patient.

Discussion

Our case illustrates the unique and challenging diagnosis of DCF given the rarity of presentation and how quickly patients may clinically decompensate. After an extensive search of the medical literature, we were only able to identify about 40 previous cases of DCF, of which 37 were described in one review.1 DCF, although rare, should be considered at risk for forming in the following settings: migrating inferior vena cava filter, right nephrectomy and radiotherapy, duodenal peptic ulcer, abdominal trauma, and oncologic settings involving metastatic malignancy requiring radiation and/or surgical grafting of the inferior vena cava.1-4 When the diagnosis is considered, computed tomography (CT) is the best initial imaging modality as it allows for noninvasive evaluation of both the inferior vena cava and nonadjacent structures. A commonality of our case and those described in the literature is the diagnostic mystery and nonspecific symptoms patients present with, thus making CT an appropriate diagnostic modality. Endoscopy is useful for the further workup of GI bleeding and the diagnosis of peptic ulcer disease.5 In our case, given the patient’s autopsy findings and history of extensive nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, the duodenal peptic ulcer was likely the precipitating factor for his DCF.