Discussion

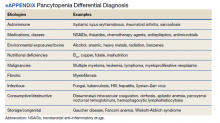

We highlight a complex case of pancytopenia secondary to pernicious anemia in a deployed service member. With limited resources downrange, the workup of pancytopenia can be resource intensive, expensive, and time sensitive, which can have detrimental impacts on medical readiness. Additionally, undiagnosed coagulopathies can have lethal consequences in a deployed service member where bleeding risk may be elevated depending on the mission. The differential for pancytopenia is vast, and given its relative rarity in pernicious anemia, the HCP must use key components of the history and laboratory results to narrow the differential (eAppendix).10

Pernicious anemia commonly presents as an isolated anemia. In a study looking at the hematologic manifestations of 201 cohort patients with well-documented vitamin B12 deficiency, 5% had symptomatic pancytopenia and 1.5% had a hemolytic anemia.2 The majority (> 67%) of hematologic abnormalities were correctable with cobalamin replacement.2 In our case, the solider presented with symptomatic anemia, manifesting as syncope, and was found to have transfusion-resistant pancytopenia.She had a hemolytic anemia with an LDH > 1000 U/L, haptoglobin < 3 mg/dL, and mild transaminitis with hyperbilirubinemia (1.8 mg/dL). No schistocytes were observed on peripheral smear, suggesting intramedullary hemolysis, which is believed to be due to the destruction of megaloblastic cells by macrophages in bone marrow.11 A French study found high LDH levels and low reticulocyte counts to be strongly suggestive of vitamin B12 deficiency and helpful in differentiating pernicious anemia from TTP, given that bone marrow response to anemia in TTP is preserved.8

While vitamin B12 deficiency is not often associated with hemolytic anemia, multiple cases have been reported in the literature.6 Screening for vitamin B12 deficiency may have shortened this patient’s clinical course and limited the need for air evacuation to a stateside quaternary medical center. However, testing for cobalamin levels in overseas deployed environments is difficult, timely, and costly. New technologies, such as optical sensors, can detect vitamin B12 levels in the blood in < 1 minute and offer portable, low-cost options that may be useful in the deployed military setting.12

Diet plays a key role in this case, since the patient had a reported history of gluten intolerance, although it was never documented or evaluated prior to this presentation. Prior to deployment, the patient ate mostly rice, potatoes, and vegetables. While deployed in an austere environment, food options were limited. These conditions forced her to intermittently consume gluten products, which led to gastrointestinal issues, exacerbating her nutritional deficiencies. In the 2 months before her first syncopal episode, she reported worsening fatigue that impacted her ability to exercise. Vitamin B12 stores often take years to deplete, suggesting that she had a chronic nutritional deficiency before deployment. Another possibility was that she developed an autoimmune gastritis that acutely worsened in the setting of poor nutritional intake. Her history of Hashimoto thyroiditis is also important, as up to one-third of patients with autoimmune thyroid disease have been associated with pernicious anemia (range, 3%-32%) with certain shared human leukocyte antigen alleles implicated in autoimmune gastritis.13,14