Results

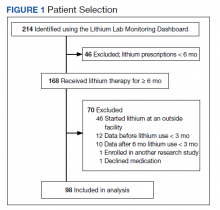

A total of 214 patients with an active prescription for lithium were identified on the Lithium Lab Monitoring Dashboard on October 31, 2017. After exclusion criteria were applied, 98 patients were included in the study (Figure 1). The 2 most common reasons for exclusion were due to patients not being on lithium for at least 6 months and being initiated on lithium at an outside facility. One patient was enrolled in a lithium research study (the medication ordered was lithium/placebo) and another patient refused all psychotropic medications according to the progress notes.

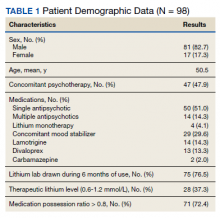

Most of the 98 patients (82.7%) were male with average age 50.5 years (Table 1). Almost half the patients (n = 47) were concomitantly participating in psychotherapy, and 50 (51.0%) patients received at least 1 antipsychotic medication. Twenty-nine patients had an active prescription for an additional mood stabilizer, and only 4 (4.1%) patients received lithium as monotherapy. Only 75 (76.5%) patients had a lithium level drawn during the 6 months of therapy, with 28 (37.3%) patients having a therapeutic lithium level (0.6 - 1.2 mmol/L). Seventy-one patients (72.4% ) were adherent to lithium therapy with a MPR > 0.8.16 Participants had 13 different psychiatric diagnoses at the time of lithium initiation; the most common were bipolar spectrum disorder (n = 38; 38.8%), depressive disorder (n = 27; 27.6%), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (n = 26; 26.5%). Of note, 5 patients had a diagnosis of only PTSD without a concomitant mood disorder.

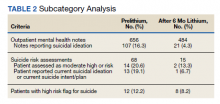

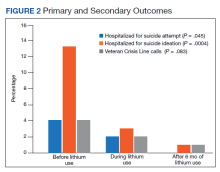

For the primary outcome, hospitalization for a suspected suicide attempt decreased from 4 (4.1%) before lithium use with a mean (SD) 0.04 (0.20) attempts per person to none within 3 months after lithium use for 6 months (t(97) = 2.03, P = .045) (Figure 2). The secondary outcome of hospitalization for suicidal ideations also decreased from 13 (13.3%) before lithium use with a mean (SD) 0.1 (0.3) ideations per person to 1 (1.0%) within 3 months after lithium use for 6 months with a mean (SD) 0.01 (0.1) ideations per person (t(97) = 3.68, P = .0004). Veteran Crisis Line calls also decreased from 4 (4.1%) with a mean (SD) 0.04 (0.2) calls per person to 1 (1.0%) within 3 months after 6 months of lithium with a mean (SD) 0.01 (0.1) calls per person (t(97) = 1.75, P = .08). The comparison of metrics from 3 months before lithium initiation and within 3 months after use saw decreases in all categories (Table 2). Outpatient notes documenting suicidal ideation decreased, as did the number of patients with a high-risk suicide flag.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest lithium may have a role in reducing suicidality in a veteran population. There was a statistically significant reduction in hospitalizations for suicide attempt and suicidal ideation after at least 6 months of lithium use. These results are comparable with a previously published study that observed significant decreases in suicidal behavior and/or hospitalization risks among veterans taking lithium compared with those not taking lithium.17 Our study was similar in respect to the reduced hospitalizations among a veteran population; however, the previous study did not report a difference in suicide attempts and lithium use. This could be related to the longer follow-up time in the previous study (3 years) vs our study (9 months).

Our study identified a significant reduction in Veteran Crisis Line calls after at least 6 months of lithium use. While a reduction in suicidal ideations could be implicated in the decrease in crisis line calls, there may be a confounding variable. It is possible that after lithium initiation, veterans had more frequent contact with health care practitioners due to laboratory test monitoring and follow-up visits and thus had concerns/crises addressed during these interactions ultimately leading to a decreased utilization of the crisis line. Interestingly, there was a reduction in mental health outpatient notes from the prelithium period to the 3-month period that followed 6 months of lithium therapy. However, our study did not report on the number of mental health outpatient notes or visits during the 6-month lithium duration. Additionally, time of year/season could have an impact on suicidality, but this relationship was not evaluated in this study.

The presence of high-risk suicide flags also decreased from the prelithium period to the period 3 months following 6 months of lithium use. High-risk flags are reviewed by the suicide prevention coordinators and mental health professionals every 90 days; therefore, the patients with flags had multiple opportunities for review and thus renewal or discontinuation during the study period. A similar rationale can be applied to the high-risk flag as with the Veteran Crisis Line reduction, although this change could also be representative of a decrease in suicidality. Our study is different from other lithium studies because it included patients with a multitude of psychiatric diagnoses rather than just mood disorders. Five of the patients had a diagnosis of only PTSD and no documented mood disorder at the time of lithium initiation. Additional research is needed on the impact of lithium on suicidality in veterans with PTSD and psychiatric conditions other than mood disorders.