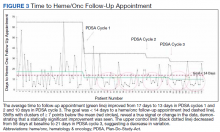

The primary endpoint of time to hematology and oncology follow-up appointment improved to 13 days in PDSA cycles 1 and 2 and 10 days in PDSA cycle 3. The target of mean 14 days to follow-up was achieved. The statistical process control chart shows 5 shifts with clusters of ≥ 7 points below the mean revealing a true signal or change in the data and demonstrating that an improvement was seen (Figure 3). Furthermore, the statistical process control chart demonstrates upper control limit decreased from 58 days at baseline to 21 days in PDSA cycle 3, suggesting a decrease in variation.

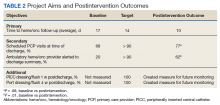

Regarding secondary endpoints, the outpatient hematology and oncology attending physician and/or fellow was alerted electronically to the discharge summary for 62% of patients compared with 20% at baseline (P = .01), and primary care appointments were scheduled for 77% of patients after the intervention compared with 68% at baseline (P = .88) (Table 2).

Through ongoing meetings, discussions, and feedback, we identified additional objectives unique to this patient population that had no performance measurement. These included peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) care nursing visits scheduled 1 week after discharge and port care nursing visits scheduled 4 weeks after discharge. These visits allow nursing staff to dress and flush these catheters for routine maintenance per institutional policy. The implementation of the discharge checklist note creates a mechanism of tracking performance in meeting this goal moving forward, whereas no method was in place to track this metric.

Discussion

The 2013 IOM report Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis found that that cancer care is not as patient-centered, accessible, coordinated, or evidence-based as it could be, with detrimental impacts on patients.3 The document offered a conceptual framework to improve quality of cancer care that includes the translation of evidence into clinical practice, quality measurement, and performance improvement, as well as using advances in information technology to enhance quality measurement and performance improvement. Our quality initiative uses this framework to work toward the goal as stated by the IOM report: to deliver “comprehensive, patient-centered, evidence-based, high-quality cancer care that is accessible and affordable.”3

Two large studies that evaluated risk factors for 15-day and 30-day hospital readmissions identified cancer diagnosis as a risk factor for increased hospital readmission, highlighting the need to identify strategies to improve the discharge process for these patients.4,5 Timely outpatient follow-up and better patient hand-off may improve clinical outcomes among this high-risk patient population after hospital discharge. Multiple studies have demonstrated that timely follow-up is associated with fewer readmissions.1,8-10 A study by Forster and colleagues that evaluated postdischarge adverse events (AEs) revealed a 23% incidence of AEs with 12% of these identified as preventable. Postdischarge monitoring was deemed inadequate among these patients, with closer follow-up and improved hand-offs between inpatient and outpatient medical teams identified as possible interventions to improve postdischarge patient monitoring and to prevent AEs.7

The present quality initiative to standardize the discharge process for the hematology and oncology service decreased time to hematology and oncology follow-up appointment, improved communication between inpatient and outpatient teams, and decreased process variation. Timelier follow-up for this complex patient population likely will prevent clinical decompensation, delays in treatment, and directly improve patient access to care.

The multidisciplinary nature of this effort was instrumental to successful completion. In a complex health care system, it is challenging to truly understand a problem and identify possible solutions without the perspective of all members of the care team. The involvement of team members with training in quality improvement methodology was important to evaluate and develop interventions in a systematic way. Furthermore, the support and involvement of leadership is important in order to allocate resources appropriately to achieve system changes that improve care. Using quality improvement methodology, the team was able to map our processes and perform gap and root cause analyses. Strategies were identified to improve our performance using a solutions approach. Changes were implemented with continued intermittent meetings for monitoring of progression and discussion of how interventions could be made more efficient, effective, and user friendly. The primary goal was ultimately achieved.

Integration of intervention into the EMR embodies the IOM’s call to use advances in information technology to enhance the quality and delivery of care, quality measurement, and performance improvement.3 This intervention offered the strongest system changes as an electronic clinical decision support tool was developed and embedded into the EMR in the form of a Discharge Checklist Note that is linked to associated orders. This intervention was the most robust, as it provided objective data regarding utilization of the checklist, offered a more efficient way to communicate with team members regarding discharge needs, and streamlined the workflow for the discharging provider. Furthermore, this electronic tool created the ability to measure other important aspects in the care of this patient population that we previously had no mechanism of measuring: timely nursing appointments for routine care of PICC lines and ports.