Results

One hundred ninety-six persons inquired about the study (Figure 1).

Of these, 97 were not qualified or not interested. Of the 99 who passed telephone screening, 81 attended the in-person eligibility assessment. Of the 81, 38 were ineligible and 18 were no longer interested in participating. Inclusion criteria ensured a homogeneous sample with respect to the most common cause of tinnitus (noise exposure) and the absence of vestibular disorders.After being deemed eligible by the otologist as having tinnitus associated with sound trauma, the remaining 25 eligible and interested candidates were randomized into the 2 treatment arms. To reduce attrition, formation of groups took into account participants’ preferred appointment days and times. When 3 or more participants were allocated to a treatment arm, group sessions were scheduled. Five (20%) participants were lost to attrition, including 1 randomized to VET CBT-T and 2 to AC who dropped out prior to receiving any intervention, and 2 randomized to VET CBT-T who dropped out after attending 1 session. Reasons stated for dropping out included concerns they would not learn new information, inability to tolerate sound in a group, unexpected moves out of the area, lack of time, loss of interest, and family emergencies.

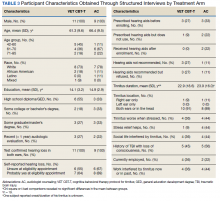

Thus, 20 participants attended the intervention sessions (11 in VET CBT-T and 9 in AC). Participants did not differ significantly between groups with respect to age, race/ethnicity, education, hearing loss, tinnitus duration, or tinnitus location (right, left, both ears, in head) (Table 3).Quantitative Analysis

Participants in the 2 treatment arms did not differ significantly on the pretreatment (t1) THI (t = 1.39, df = 18, P = .18) or TRQ (t = 0.99, df = 18, P = .33) scores. Differences in THI scores were computed from pre- to posttreatment (VET CBT-Tt1−t2 = 6.2; ACt1−t2 = 10.0) and from pretreatment to 8-week follow-up (VET CBT-Tt1−t3 = 4.4; ACt1−t3 = 9.1). Similarly, differences in mean TRQ index scores were computed from pre- to posttreatment (VET CBT-Tt1−t2 = 5.3; ACt1−t2 = 7.6) and from pretreatment to 8 weeks follow-up (VET CBT-Tt1−t3 = 1.5; ACt1−t3 = 5.6). These mean differences reveal consistent reductions in mean index scores (improved tinnitus-related QOL) between time points for each treatment arm, but do not indicate statistically or clinically significant reductions of distress.

Qualitative Analysis

The 89 comments that participants provided after the 18 VET CBT-T sessions (3 series of 6 sessions each) were mostly positive (67 responses, 75%) (eTable 2).

Most veterans described VET CBT-T as acceptable and beneficial. The remaining comments were either neutral (14 responses, 16%) or negative (8 responses, 9%). Several important themes emerged from these comments and were also observed in transcripts.Components of VET CBT-T and Number of Sessions (n = 53)

Psychoeducation and Sound Enrichment. Participants generally appreciated the psychoeducation component of VET CBT-T, including basic information about the prevalence of tinnitus, mechanics of the ear and hearing, and how an enriched sound environment may assist with coping (5 comments).