Results

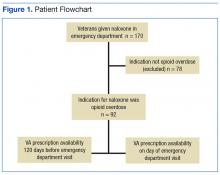

The ED at the George E. Wahlen VAMC averages 64 visits per day, almost 94,000 visits within the study period. One hundred seventy ED visits between January 1, 2009 and January 1, 2013, involved naloxone administration. Ninety-two visits met the inclusion criteria of opioid overdose, representing about 0.002% of all ED visits at this facility (Figure 1). Six veterans had multiple ED visits within the study period, including 4 veterans who were in the opioid-only group.

The majority of veterans in this study were non-Hispanic white (n = 83, 90%), male (n = 88, 96%), with a mean age of 63 years. Less than 40% listed a next-of-kin or contact person living at their address.

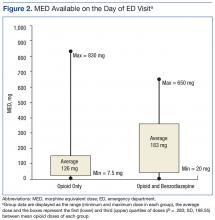

Based on prescriptions available within 120 days before the overdose, 67 veterans (73%) possessed opioid and/or BZD prescriptions. In this group, the MED available on the day of the ED visit ranged from 7.5 mg to 830 mg. The MED was ≤ 200 mg in 71.6% and ≤ 50 mg in 34.3% of these cases. Veterans prescribed both opioids and BZDs had higher MED (average, 259 mg) available within 120 days of the ED visit than did those prescribed opioids only (average, 118 mg) (P = .015; SD, 132.9). The LED ranged from 1 mg to 12 mg for veterans with available BZDs.

Based on prescriptions available on the day of opioid overdose, 53 veterans (58%) had opioid prescriptions. The ranges of MED and LED available on the day of overdose were the same as the 120-day availability period. The average MED was 183 mg in veterans prescribed both opioids and BZDs and 126 mg in those prescribed opioids only (P = .283; SD, 168.65; Figure 2). The time between the last opioid fill date and the overdose visit date averaged 20 days (range, 0 to 28 days) in veterans prescribed opioids.

All veterans had at least 1 diagnosis that in previous studies was associated with increased risk of overdose.9,15 The most common diagnoses included cardiovascular diseases, mental health disorders, pulmonary diseases, and cancer. Other SUDDs not including tobacco use were documented in at least half the veterans with prescribed opioids and/or BZDs. No veteran in the sample had a documented history of opioid SUDD.

Hydrocodone products were available in > 50% of cases. None of the veterans were prescribed buprenorphine products; other opioids, including tramadol, comprised the remainder (Figure 3). Primary care providers prescribed 72% of opioid prescriptions, with pain specialists, discharge physicians, ED providers, and surgeons prescribing the rest. When both opioids and BZDs were available, combinations of a hydrocodone product plus clonazepam or lorazepam were most common. The time between the last opioid fill date and the overdose visit date averaged 20 days (range, 0 to 28 days) in veterans prescribed opioids.

Overall, 64% of the sample had UDS results prior to the ED visit. Of veterans prescribed opioids and/or BZDs, 53% of UDSs reflected prescribed regimens.

On the day of the ED visit, 1 death occurred. Ninety-one veterans (99%) survived the overdose; 79 veterans (86%) were hospitalized, most for < 24 hours.

Discussion

This retrospective review identified 92 veterans who were treated with naloxone in the ED for opioid overdose during a 4-year period at the George E. Wahlen VAMC. Seventy-eight cases were excluded because the reason entered in charts for naloxone administration was itching, constipation, altered mental status, or unclear documentation.

Veterans in this study were older on average than the overdose fatalities in the U.S. Opioid overdose deaths in the U.S. and in Utah occur most frequently in non-Hispanic white men aged between 35 and 54 years.7,22,23 In the 2010 Nationwide Emergency Department Sample of 136,000 opioid overdoses, of which 98% survived, most were aged 18 to 54 years.16 The older age in this study most likely reflects the age range of veterans served in the VHA; however, as more young veterans enter the VHA, the age range of overdose victims may more closely resemble the age ranges found in previous studies. Post hoc analysis showed 8 veterans (9%) with probable intentional opioid overdose based on chart review, whereas the incidence of intentional prescription drug overdose in the U.S. is 17.1%.24

In Utah, almost 93% of fatal overdoses occur at a residential location.22 Less than half the veterans in this study had a contact or next-of-kin listed as living at the same address. Although veterans may not have identified someone living with them, in many cases, it is likely another person witnessed the overdose. Relying on EMRs to identify who should receive prevention education, in addition to the veteran, may result in missed opportunities to include another person likely to witness an overdose.25 Prescribers should make a conscious effort to ask veterans to identify someone who may be able to assist with rescue efforts in the event of an overdose.

Diagnoses associated with increased risk of opioid overdose death include sleep apnea, morbid obesity, pulmonary or cardiovascular diseases, and/or a history of psychiatric disorders and SUDD.8,9,16 In a large sample of older veterans, only 64% had at least 1 medical or psychiatric diagnosis.26 Less than half the 18,000 VA primary care patients in 5 VA centers had any psychiatric condition, and < 65% had cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, or cancer.27 All veterans in this study had medical and psychiatric comorbidity.

In contrast, a large ED sample described by Yokell and colleagues found chronic mental conditions in 33.9%, circulatory disorders in 29.1%, and respiratory conditions in 25.6% of their sample.16 Bohnert and associates found a significantly elevated hazard ratio (HR) for any psychiatric disorder in a sample of nearly 4,500 veterans. There was variation in the HR when individual psychiatric diagnoses were broken out, with bipolar disorder having the largest HR and schizophrenia having the lowest but still elevated HR.9 In this study, individual diagnoses were not broken out because the smaller sample size could diminish the clinical significance of any apparent differences.

Edlund and colleagues found that < 8% of veterans treated with opioids for chronic noncancer pain had nonopioid SUDD.10 Bohnert and colleagues found an HR of 21.95 for overdose death among those with opioid-use disorders.9 The sample in this study had a much higher incidence of nonopioid SUDD compared with that ub the study by Edlund and colleagues, but none of the veterans in this study had a documented history of opioid use disorder. The absence of opioid use disorders in this sample is unexpected and points to a need for providers to screen for opioid use disorder whenever opioids are prescribed or renewed. If prevention practices were directed only to those with opioid SUDDs, none of the veterans in this study would have been included in those efforts. Non-SUDD providers should address the risks of opioid overdose in veterans with sleep apnea, morbid obesity, pulmonary or cardiovascular diseases, and/or a history of psychiatric disorders.