Phase 2 involved collecting medication data. Medication lists from the VA medical record were printed at the time of the non-VA provider appointment. Non-VA medication lists were obtained by sending a medical record request for the visit note, medication list, and any associated visit test results to the non-VA provider office within 2 to 3 weeks of the appointment. Patient names from both lists were replaced with unique patient identifiers.

In phase 3, a research assistant abstracted the hard copy medication lists into a database and identified discrepancies. Variables included medication name, dose, frequency, and administration route. Although administration routes were collected, discrepancies were not assessed because this information commonly was not specified. Medications also were coded as prescription or over-the-counter (OTC). Durable medical equipment often was present on VA lists (eg, syringes, test strips) and was excluded from all analyses. Medications also were not coded as discrepant if they were referenced in a visit note as being changed by the non-VA provider. These combined lists were evaluated by the research assistant based on the discrepancy categories specified in phase 1 and were verified by a pharmacist.

Phase 4 involved counting medication discrepancies. Medication discrepancy rates were calculated at the patient level, both descriptively (mean number of discrepancies per patient) and as a proportion of medications discrepant (number of discrepancies divided by total medications).

Identifying Duplications and High-Risk Medications

A pharmacist examined each combined medication list to identify therapeutic duplications, defined as a patient using ≥ 2 medications from the same medication class (eg, patient taking 2 statin drugs) but not 2 drugs for the same condition (eg, fish oil and atorvastatin for dyslipidemia). High-risk medications also were noted, including anticoagulants, certain nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, oral and injectable hypoglycemics, opioids, sedatives, and hypnotics.24-26 These medications received special focus because of their link to a high risk for ADRs.27

Descriptive statistics were calculated for patient characteristics and for each discrepancy type, both overall and according to prescription OTC, and high-risk medications. The proportion of discrepant medications was calculated for each category. Bivariate correlations were calculated for select variables to understand potential relationships.

Interviews With Non-VA Providers

All patients were instructed to bring a consent letter and the 1-page questionnaire to their non-VA provider appointment. The questionnaire contained an item asking whether non-VA providers could be contacted for a 15- to 30-minute follow-up interview. The semistructured, qualitative interviews assessed their experiences working with VA providers and VA patients, experiences with VA documents or records, preferences for receiving information from the VA, experience with personal health records, and sharing information with the VA. Eight interviews were conducted, audio-recorded, and transcribed. The goal of the interviews was to explore and understand provider perspectives on managing dual use veterans, including medication reconciliation processes to add context to the interpretation of medication list analysis. Because the data set was relatively small, summaries of each interview were created to highlight main points. These main points were sorted into topics, summarized, and representative quotes were selected.

Results

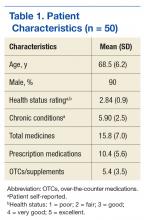

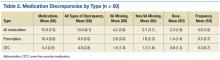

Fifty veterans were included in the analysis (Table 1). The mean age was 68.5 (SD 6.2); 90% were men. On average, they reported having 6 chronic health conditions and a fair-to-good health status. Based on the combined medication lists from VA and non-VA providers, veterans took an average of 15.8 (SD 7.0) unique medications (combined prescription and OTC/vitamins) and had an average of 10.0 (SD 6.1) all-type discrepancies (Table 2).

Overall, 58% of the prescription medications were discrepant: The most common discrepancy between the 2 lists was medication missing on one of the lists, which occurred 3.9 times per patient on average for prescription medications and 2.8 times per patient for OTCs. Frequency or dose discrepancies also were common between the lists at a rate of 1.9 discrepancies per patient for prescription medications and 1.2 discrepancies per patient for OTCs.

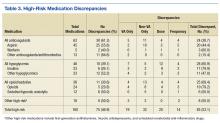

For high-risk medications, opiates and sedative medications had the most discrepancies between the lists because the VA practitioner may not have known that the patient was taking an opiate, although other discrepancies were present (Table 3). Anticoagulant discrepancies were the most consistent, most of these occurring with aspirin. Last, insulin commonly was dose discrepant between the 2 lists, although it also was missing from one list for a number of patients. Overall, high-risk medications shared a discrepancy rate (46.9%) similar to the overall rate.

Twelve therapeutic duplications were identified in the sample.Ten were between-list duplications, that is, “provider A” thought the patient was on a particular medication and “provider B” thought that the patient was on a different medication (Table 4). In 6 instances, within-list duplications were identified (ie, a provider had 2 medications on the list that should not be taken together because they were in the same drug class). In 4 cases, both between- and within-list duplications were present.