Chronic hepatitis B infection in Asian immigrants is often due to perinatal transmission in their home countries. Rates of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in the United States have been steadily declining since vaccination began in 1981. However, chronic HBV infection in Asian immigrants approaches 10% of that population.16 An estimated 15% to 20% of patients with chronic HBV develop cirrhosis within 5 years and are at high risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).17,18

Evaluate HBV carriers annually with liver function testing (LFTs), hepatitis B surface Antigen (HBsAg), and hepatitis B e-Antigen (HBeAg). A positive HBsAg result indicates the virus is present; a positive HBeAg result indicates the virus is actively replicating. LFT elevation (AST >200 IU/L) or a positive HBeAg test should prompt referral to a gastroenterologist for liver biopsy and therapy. Screening for HCC with alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels and liver ultrasounds every 6 to 12 months has been recommended for all chronic HBV carriers,19 but this interval remains controversial. Screen men ≥40 years and women ≥50, or anyone who has had HBV infection >10 years, every 6 months.19,20 More recent recommendations favor ultrasound over AFP for screening, as the latter test lacks adequate sensitivity and specificity.20 Test partners and family members of HBV patients, and vaccinate them against HBV if not already immune.

Other medical issues. Asians from the Indian subcontinent have a significantly elevated risk of heart disease, in part due to low HDL-cholesterol levels.21 South Asian immigrant populations have a 3- to 5-fold increased risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death compared with other ethnicities, and often exhibit coronary disease before the age of 40.22 The recent adoption of a Western diet and sedentary lifestyle has provoked an epidemic of diabetes throughout urban Asia and in Asians living abroad. This may be related to the “thrifty gene hypothesis,” which suggests that genes which evolved early in human history to facilitate storage of fat for periods of famine are detrimental in modern society where food is plentiful. A study of Asian Indian immigrants in Atlanta demonstrated an 18.3% prevalence rate for diabetes, higher than any other ethnic group.23 Tobacco and its causal relationship with lung cancer and heart disease only adds to this concern. Southeast Asians in particular demonstrate alarmingly high rates of tobacco consumption, and lung cancer is the leading cause of death among Asian Americans.12,24

Recently, a new acquired immune deficiency syndrome has been described in East Asia. In this syndrome, interferon–gamma (IFN–gamma) is blocked by an auto-antibody. Although not communicable like human immunodeficiency virus, this autoimmune syndrome may lead to similar opportunistic infections such as atypical mycobacterial infections.25

Mental health concerns

Perhaps no topic deserves more emphasis than that of mental health. In the aftermath of the war in Vietnam, Southeast Asian immigrants suffered a great deal from traumatic immigration experiences, with severe adjustment reactions.26 A high incidence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among the Hmong in particular reflects their turbulent national history.27

While the incidence of mental illness among Asians is comparable to that of the general population, Asian Americans are less likely to report such problems or to use mental health services26 due to the stigmatization of mental illness in Asian culture.28 Consequently, these symptoms may be subconsciously converted into the more socially acceptable medium of physical illness, which “saves face” and preserves family honor.29 In many ways, Asian culture still perceives mental illness as personal weakness.30 In Hmong culture, inability to speak about being depressed stems not just from cultural bias but from linguistic constraints—the language simply lacks a word for depression.31 Even Asian cultures recognizing mental illness deem depression to be more dependent on circumstances than on the psyche.31 A first-generation immigrant with mental illness is therefore more likely to present with somatic symptoms than a mood disturbance, and is likely to be resistant to counseling or medication for depression. (See “Cultural influence on self-perception: A case ”).

Asian health care beliefs and illnesses

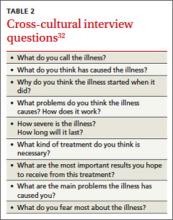

Asian culture substantially influences the ways in which an individual perceives disease, experiences illness, and copes with the phenomenon of sickness. The interplay between illness, disease, and sickness was first elucidated by the pioneering work of Arthur Kleinman, MD, in 1978.32 The term disease denotes a pathological process, while illness describes the subjective impact of disease in a patient’s life. Sickness is the sum of both, as it relates to the total picture of biological and social disruption. The culturally competent physician must understand not only the patient’s disease but also his experience of illness. Asking Dr. Kleinman’s questions will help physicians understand their patient’s perception of illness (TABLE 2).32