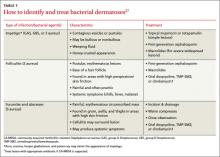

There are several types of bacterial dermatoses: impetigo, folliculitis, furuncles, carbuncles, abscesses, and cellulitis. Most are caused by group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus or S aureus and can be easily treated, but identification of the pathogen is needed to facilitate healing and a safe return to play (TABLE 1).27

When to suspect CA-MRSA

Community-acquired methicillin-resistant S aureus (CA-MRSA) was first reported in an athletic population in the 1960s, and in 1993 the first documented outbreak of CA-MRSA in a sports setting—involving 6 high school wrestlers from Vermont—was reported.28

The athlete with CA-MRSA usually presents with a painful, purulent, swollen, red abscess-like lesion, sometimes described as (or mistaken for) a spider bite. The patient may also develop fever, fatigue, and malaise. Culturing the wound for identification of the bacterium and for susceptibility to antibiotic therapy is needed for a definitive diagnosis of CA-MRSA.

Is incision and drainage sufficient treatment? The standard treatment for uncomplicated CA-MRSA lesions is incision and drainage. Several studies have found this to be adequate for simple lesions.29 Others have reported increased treatment failure with simple incision and drainage and shown that the addition of antimicrobial therapy helps decrease further tissue damage and morbidity.29

With no clear consensus as to when and whether to add oral antibiotic therapy after incision and drainage of a CA-MRSA lesion, decisions should be based on the severity of the lesion, the presence or absence of systemic symptoms, and the potential risk of bacterial spread to other team members.

Choosing an antimicrobial agent. Antimicrobial treatment should be guided by culture and sensitivity results, as well as the regional incidence of CA-MRSA. Empiric treatments for CA-MRSA are trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, and clindamycin, taken for 7 to 14 days. If you’re considering the use of clindamycin and there is known resistance to erythromycin from antimicrobial sensitivities, a double disc diffusion (D-test) should be ordered to detect inducible macrolide resistance that can occur in some strains of CA-MRSA.29,30

Fluoroquinolones and certain macrolides should not be used, due to resistance to these antibiotics.1

Topicals for superficial lesions. Topical antibiotic therapy with mupirocin or retapamulin should be reserved for superficial CA-MRSA lesions, such as impetigo.31,32 Caution must be used when mupirocin is prescribed, however, due to recent studies showing increasing resistance to mupirocin, especially when used for nasal decolonizing purposes.29

Once treatment is initiated, see the athlete every 2 to 3 days. Resolution usually occurs in 10 to 14 days. The athlete can return to play after 72 hours of treatment, however, provided there is evidence of clinical improvement, no further drainage from the infected lesion, and no new lesions have developed.1,30

Containing CA-MRSA. Mass nasal decolonization—applying topical mupirocin in the nares of infected athletes as well as their teammates—has been attempted to prevent the spread of CA-MRSA. But there is no evidence to suggest that mupirocin or any other intranasal antimicrobial is effective in preventing the spread of CA-MRSA, and nasal decolonization should not be attempted in any community setting.29 In fact, studies have found that attempts at nasal decolonization can actually lead to increased bacterial resistance and a recurrence of colonization.29,31,32

HSV-1 is highly prevalent

Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) is a common problem in athletes who play team sports that involve skin-to-skin contact. It is particularly prevalent among competitive wrestlers—earning it the name herpes gladiatorum.

In fact, HSV-1 is widespread throughout the country: Its prevalence in the general population is 58%.33 It is estimated that nearly half (47%) of cutaneous infections in collegiate athletes are caused by the herpes virus, making HSV-1 the most common pathogen of skin infections in this group.34 The clinical presentation of active HSV-1 depends on whether the infection is primary or recurrent.

So which form of HSV-1 is it?

Primary lesions may be preceded by a prodromal period with systemic symptoms, such as fever. Oral lesions and enlarged cervical and submandibular lymph nodes follow.35 The lesions, which are typically painful, can be found on the lips, buccal mucosa, or tongue—nearly anywhere in and around the oral cavity (Figure 2). They are vesicular at first, then ulcerate. Healing typically takes 10 to 14 days.36

In recurrent HSV-1, clusters of vesicles with erythematous borders typically occur. In those who play contact sports, HSV lesions can be found not only in the typical facial and oral areas, but anywhere on the head, face, torso, or extremities, as well.

Identifying herpetic whitlow. Presenting as a cluster of herpetic vesicles on the hands, fingers, or toes, herpetic whitlow is a common presentation of recurrent HSV-1. Recognition of these lesions is usually adequate for a diagnosis of recurrent infection, but confirmation can be obtained by laboratory or serologic testing.