Poll finds that patients and providers don’t see eye to eye

In February 2010, Annals of Internal Medicine conducted a Web-based survey relating to the USPSTF’s new screening guidelines. Of the 651 respondents, more than half (54%) were physicians, 9% were nonphysician health care providers, and 37% were potential patients. The findings suggest that health care providers and those they treat do not always see eye-to-eye when it comes to breast cancer screening.20

Two-thirds of the health care professionals surveyed said they would stop offering routine mammograms to women ages 40 to 49, in accordance with the USPSTF’s recommendation, and 62% would advise women ages 50 to 74 to have biennial, rather than annual, mammograms. In addition, 54% of clinicians indicated that they would stop recommending routine screening mammography to women who are 75 or older—a group for whom the USPSTF has stated that evidence is insufficient to assess the benefits and harms of screening. In contrast, 71% of the women said they were unlikely to forego routine mammography in their 40s—and less than 20% said they would wait until age 50 to begin screening or opt for biennial, rather than annual, screenings.20 Although the women’s views may be similar to those held by many of your female patients, the American Cancer Society estimates that about half of US women who are eligible for screening do not get mammograms.21

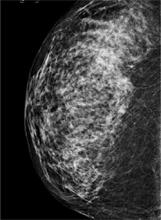

FIGURE

A digital mammogram showing normal but dense breast tissue

What is your patient’s level of risk?

Individual risk assessment, as stated earlier, is a key factor in determining whether to initiate screening for women younger than 50. It’s important to keep in mind, however, that only half of all breast cancers occur in women with well-established risk factors, including family history, a variety of reproductive risk factors, a high body mass index, and exposure to exogenous estrogen. Fully 50% of women who develop breast cancer are not at elevated risk.13

New models to aid in the shared decision-making process and risk assessment are being developed. One example is a Web-based interactive tool developed by researchers at the University of Sydney to give women in their 40s the information they need to make an informed decision about whether to start screening before age 50 (http://www.mammogram.med.usyd.edu.au/).22 This decision tool answers 2 key questions for women who are not at elevated risk for breast cancer:

| Q: | How many 40-year-old women who start having screening mammograms every 2 years will die from breast cancer in the next 10 years? |

| A: | Out of 1000 40-year-old women who start having screening mammograms every 2 years for the next 10 years, 2 women will die of breast cancer. |

| Q: | How many 40-year-old women who do not have screening mammograms will die from breast cancer in the next 10 years? |

| A: | Out of 1000 40-year-old women who do not have screening mammograms every 2 years for the next 10 years, 2.5 women will die of breast cancer.22,23 |

To our knowledge, there is no such patient-focused decision aid intended for use in the United States. There are assessment tools recommended for use by health care professionals, however. The interactive Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool, also known as the Gail Model (http://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool), provides a population-based, rather than an individualized, estimate of a woman’s risk of developing invasive breast cancer in the next 5 years, as well as her lifetime risk. It incorporates current age, age at menarche, age at parity, number of first-degree maternal relatives with breast cancer, number of breast biopsies, and history of atypical hyperplasia. However, the Gail Model has a C-statistic (a measure of how well a clinical prediction tool correctly ranks patient risk) of just 0.5 to 0.6, which is slightly better than chance. The addition of breast density as a risk criterion in an attempt to boost the tool’s predictive value resulted in minimal improvement. 24,25

A novel approach. In the absence of ideal screening methodology or risk assessment tools, the authors of a recent cost-effectiveness analysis suggest a novel approach: They recommend that all women have a screening mammogram at the age of 40. The primary purpose is to assess breast density.26 That assessment should be key in making decisions about future screenings, as increased breast density is associated with a 4-fold increase in breast cancer risk.27,28

Faced with 2 very different recommendations for breast cancer screening from 2 very reputable organizations, JFP asked these physicians how they handle the mammography controversy, and what they recommend that primary care physicians do.

| Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD | Jane L. Murray, MD | Cheryl Iglesia, MD, FACOG |

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine and a member of the editorial board of OBG Management, says he continues to recommend mammography to all women ages 50 and older, regardless of risk. He has stopped “nagging” women to get screened, however, and—in the absence of elevated risk—has become more flexible about the frequency of mammograms and the age at which to initiate screening.

Dr. Kaunitz encourages women in their 40s to be screened if they have a history of breast cancer, a high body mass index, or other risk factors. If a woman in her 40s is not at elevated risk but is more comfortable being screened, he says, “I’ll order a mammogram for her, too. I’m certainly not going to stand in the way.”

Most women in their 50s prefer annual mammography, Dr. Kaunitz has found, although some appreciate his flexibility. “We recently moved to an office with imaging facilities and I often tell women they can wait until their next visit to be screened—which may be 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, or more.” Others are “aghast” if their physician does not recommend an annual mammogram.

Jane L. Murray, MD, founder of the Sastun Center of Integrative Health Care in Overland Park, Kan, and a member of the editorial board of The Journal of Family Practice, maintains a similar approach.

“I tell patients that the latest guidelines from an unbiased group [USPSTF] state that low-risk women—women who have no family history of breast cancer and are not taking hormones—can begin screening at age 50 and have mammograms every other year,” Dr. Murray says. “I recommend imaging if there is any suspicion at all.”

About two-thirds of her patients are happy to hear that an annual mammogram is no longer necessary. Some patients insist on annual screening—”‘My best friend got breast cancer,’ they often say.”

Dr. Murray’s approach to screening for patients at low risk for breast cancer is to explain that mammograms aren’t perfect and can miss some tumors and overdiagnose others. “Nonetheless, they’re the best we’ve got,” she tells patients, adding, “I recommend screening, but you decide for yourself. “If I thought mammography was a perfect test, I’d be a lot more adamant,” she says.

Cheryl Iglesia, MD, FACOG, is director, section of female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery at Washington (DC) Hospital Center, and a member of the board of OBG Management. Dr. Iglesia was chair of ACOG’s gynecologic practice committee and helped to develop the organization’s new guidelines, and has a different view.

“After reviewing all the data, I think that the most important thing that came out of it is that in women ages 40 through 49, breast cancers are more aggressive than they are in older, post-menopausal women.” Thus, she recommends routine screening for women in this age group. “A practice that delays screening until age 50,” she observes, “may be missing the boat.”

Dr. Iglesia also recommends that women in their 40s receive annual mammograms—a practice that’s in line with the recommendations of the American Cancer Society and one that she herself adheres to. The interval between when a cancer is detectable on mammography and the time it becomes symptomatic—known as the “sojourn time”—is about 2 years for women ages 40 through 49, she explains, and more frequent screening would be more likely to catch breast cancer in the preclinical phase. “That’s what a screening test is supposed to do.”

Helen Lippman, Managing Editor