Use the Ottawa Knee Rules. When there is a possibility of fracture, they can guide the use of radiography in adults who present with isolated knee pain. However, information on use of these rules in the pediatric population is limited (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on systematic review of high-quality studies and a validated clinical decision rule). Specific physical examination maneuvers (such as the Lachman and McMurray tests) may be helpful when assessing for meniscal or ligamentous injury (SOR: C, based on studies of intermediate outcomes).

Sonographic examination of a traumatized knee can accurately detect internal knee derangement (SOR: C, based on studies of intermediate outcomes). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the knee is the noninvasive standard for diagnosing internal knee derangement, and it is useful for both adult and pediatric patients (SOR: C, based on studies of intermediate outcomes).

Ottawa rules for ankles—yes, but they’re good for knees, too

Daniel Spogen, MD

University of Nevada, Reno

The evidence presented here suggests a number of practical and useful approaches for the evaluation of acute knee injury—something that’s especially helpful for family physicians and those who, like me, have worked a lot of sporting events.

The Ottawa rules, which can be used to rule out fracture without an x-ray, are fairly well known for ankle injuries, but are not as well known for knees. A Lachman test, Drawer sign, and McMurray test are useful in diagnosing the presence of internal ligamentous injuries without MRI, and an ultrasound can help to detect knee effusion when it is not clinically obvious.

A good physical examination and an ultrasound can effectively rule out serious knee injury with high specificity. When serious injury is suspected, x-ray and MRI are very useful for fracture and ligamentous injury, respectively.

Evidence summary

These criteria help determine who needs an x-ray

The Ottawa Knee Rules recommend knee x-rays for any patient meeting one of these criteria:1

- ≥55 years of age

- Tenderness over the head of the fibula or isolated to the patella without other bony tenderness

- Unable to flex the knee to 90°, or unable to bear weight (for at least 4 steps) both immediately and in the emergency department.

Ottawa rules for knee x-ray

A knee x-ray is required only for knee injury patients with any of these findings:

- 55 years of age or older

- isolated tenderness of the patella (no bone tenderness of the knee other than the patella)

- tenderness at the head of the fibula

- inability to flex the knee to 90°

- inability to weight bear both immediately and in the ED (4 steps, unable to transfer weight twice onto each lower limb regardless of limping). (www.gp-training.net/rheum/ottawa.htm)

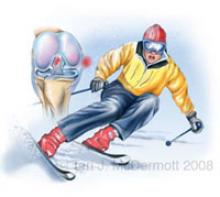

A downhill skier is catching the inside edge of the front of a ski in the snow, forcing external rotation of the tibia relative to the femur. The detail of the knee joint shows injury to the medial collateral ligament and anterior cruciate ligament.

In a systematic review,2 the Ottawa rules had a pooled negative likelihood ratio (LR–) of 0.05 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.02–0.23). A prospective study of the Ottawa rules among children with acute knee injury demonstrated a positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of 1.81 (95% CI, 1.47–2.21) and an LR– of 0.16 (95% CI, 0.02–1.04).3 However, limited information is available in the pediatric population.

Ultrasound and MRI both perform well

Physical examination (including the Lachman test, Drawer sign, and McMurray test) by an orthopedist or sports medicine–trained physician was 74% to 88% sensitive and 72% to 95% specific for suspected meniscal or ligamentous injuries; MRI added marginal value in referral decisions regarding these conditions.4

In a small nonrandomized study of adult knee trauma, sonographic diagnosis of an effusion (by an expert) had an LR+ for diagnosing an internal derangement of the knee of 2.0 (95% CI, 0.67–5.96) and an LR– of 0.33 (95% CI, 0.12–0.96), as compared with the gold standard of MRI.5

In a nonrandomized prospective study of adults receiving MRI of the knee prior to arthroscopy, MRI identified meniscal and ligamentous lesions of the knee satisfactorily (Table 1).6 In a retrospective study of adolescents (11 to 17 years of age) having knee MRIs and undergoing knee surgery, MRI compared favorably with the operative (gold standard) diagnosis (Table 2).7

TABLE 1

MRI can accurately identify meniscal and ligamentous knee lesions in adults

| INJURY | LR+ | LR– |

|---|---|---|

| Medial meniscus | 13.7 | 0.02 |

| Lateral meniscus | 14.3 | 0.08 |

| Anterior cruciate ligament | 21.5 | 0.01 |

| Posterior cruciate ligament | 100 | 0.01 |

| Intra-articular cartilage lesion | 14.9 | 0.25 |

| *Adapted from Vaz et al,2005.6 | ||

| MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; LR, likelihood ratio. | ||