A review of the patient’s blood pressure since admission indicated consistently elevated systolic and diastolic pressures, on average, of 170/105 mm Hg. Additionally, his serum potassium levels ranged from 2.4 to 3.1 mmol/L (normal 3.5-5.1 mmol/L).

A detailed medical history and review of previous records revealed that an initial diagnosis of hypertension had been made during a routine sports physical at age 14, although the patient was cleared for full activity. Over the previous year, the patient said he had gained weight—much of it in the abdomen—and experienced sleep disturbances, increasing fatigability, muscle weakness, hair loss, and declining performance in his high school sports. In addition, he had noticed increased facial flushing and sweating.

On physical exam, we noted an obese male (height 5’5’’, weight 191.5 lb, BMI 30.86 kg/m2) with the following vital signs: temperature 97.9°F, pulse 105 bpm, and blood pressure 177/111 mm Hg. Pertinent physical exam findings outside of his surgical site included diffusely thinning hair, moon facies, facial plethora, increased supraclavicular and dorsocervical fat pads, thoracic and abdominal striae, thinned skin overlying his upper and lower extremities, and lower extremity edema ( FIGURE 1 ). All other exam findings were within normal limits.

Initial blood chemistry lab results revealed hyperglycemia (290 mg/dL; random normal, <200 mg/dL), hypokalemia (3.0 mmol/L; normal, 3.5-5.4 mmol/L), hypochloremia (96 mmol/L; normal, 98-107 mmol/L), and a mean corpuscular volume of 101.2 fL (normal, 80-100 fL). The patient also had a white blood cell (WBC) count of 14,400/mcL with a predominance of neutrophils and 6 bands, and a high sensitivity C-reactive protein level of 7.5 mg/dL (normal, <0.748 mg/dL).

FIGURE 1

The signs were all there

Our patient exhibited thinning hair (A), moon facies (B), dorsocervical fat pads (“buffalo hump”) (C), and abdominal striae (D).

WHAT ADDITIONAL TESTING WOULD YOU ORDER?

WHAT IS YOUR PRESUMPTIVE DIAGNOSIS?

Suspecting Cushing’s syndrome, we ordered cortisol and ACTH

Based on our initial findings, we ordered a 24-hour urinary free cortisol and plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) level—both of which had to be sent to outside laboratories. We also ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan of the patient’s adrenal glands and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of his pituitary gland.

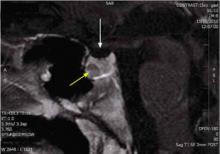

The CT scan revealed mild hyperplasia of the adrenal glands bilaterally; the MRI demonstrated a 7 × 6 × 6 mm pituitary microadenoma ( FIGURE 2 ) in the anterior portion of the gland. In addition, a 6 × 6 × 1 mm lesion was noted—thought to be a Rathke’s cleft (Pars intermedia) cyst by the reviewing radiologist.

The patient’s initial cortisol and ACTH lab work revealed a urinary cortisol level of 5089.2 mcg/24 h (normal, 3-55 mcg/24 h) and an ACTH level of 216 pg/mL (normal, 9-57 pg/mL for ages 3-17 years).

We diagnosed Cushing’s syndrome in this patient.

FIGURE 2

MRI reveals pituitary microadenoma

The patient had a microadenoma in the anterior portion of the pituitary gland (yellow arrow), and a lesion believed to be a Rathke’s cleft cyst (white arrow).

Differentiating between ACTH-dependent and -independent Cushing’s syndrome

Cushing’s syndrome is a constellation of signs and symptoms caused by an overproduction of cortisol, which results in a variety of abnormalities in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. In general, the syndrome is differentiated as either ACTH-dependent or ACTH-independent, based on the underlying cause.1 Examples of ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome include pituitary adenoma (formally classified as Cushing’s disease) and ectopic ACTH or corticotrophin-releasing hormone-producing tumors. Examples of ACTH-independent Cushing’s syndrome include adrenal adenoma or carcinoma and exogenous glucocorticoid therapy.2

Clinical manifestations include obesity, hypertension (usually with some degree of concurrent hypokalemia), skin abnormalities (eg, plethora, hirsutism, violaceous striae), musculoskeletal weakness, neuropsychiatric symptoms (eg, depression), gonadal dysfunction, and metabolic derangements, including glucose intolerance, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. In children, a near universal decrease in linear growth secondary to hypercortisolism is seen.3

Investigating a suspected case of Cushing’s syndrome can be divided into 2 stages: confirming the diagnosis and establishing the etiology. The following tests can be used to make the diagnosis: 24-hour urinary free cortisol, low-dose dexamethasone suppression, and late-night salivary cortisol. Several of these tests require late-night administration that necessitates hospital admission. These tests are typically followed by a CT scan of the patient’s adrenal glands and/or an MRI of the patient’s pituitary gland to evaluate the etiology. Additionally, as demonstrated by the patient described here, ongoing issues with hypertension, metabolic abnormalities, and hyperglycemia may require intensive intervention and management.4

Don't be fooled

Potential complications in diagnosing the syndrome, however, can cloud an accurate diagnosis—especially early in the disease process. In addition to biochemical similarities between Cushing’s syndrome and obesity, depression, and alcoholism, ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome can undergo cyclical or intermittent activity and can remain in remission for years.1 Also, ectopic ACTH-secreting tumors may, by virtue of their small size and location, go undetected.