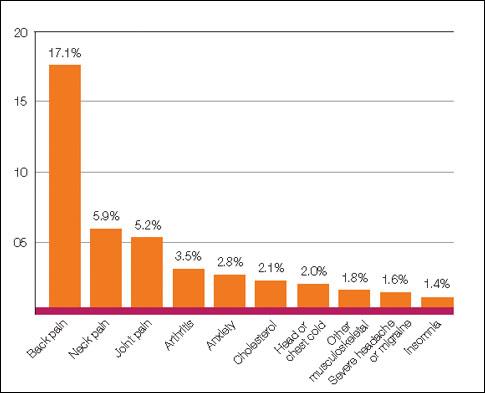

At last count in 2008, 27 million Americans were suffering with osteoarthritis (OA), by far the most common form of arthritis.1 That number has undoubtedly risen and will continue to do so as Baby Boomers age. Despite the benefits of conventional nonpharmacologic measures and available pharmacologic agents, many patients with OA achieve less than satisfactory pain relief and have impaired joint mobility, which can significantly limit their daily activities.2 Numerous studies have found that a host of complementary and alternative (CAM) therapies can provide safe and effective pain relief and enhanced joint mobility. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Therapies found that musculoskeletal problems such as back pain, neck pain, joint pain, and arthritis were the top conditions for which adults used CAM therapies in 2007 [Figure 1].3

| FIGURE 1: Diseases/conditions for which CAM is most frequently used among US adults – 2007 |

| Source: Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin R. CDC National Health Statistics Report #12. Complementary and alternative medicine use amongadults and children. United States, 2007. December 2008. |

A survey to gather detailed information about CAM use by patients with arthritis (n 5 2140) found that most patients followed by specialists (90.5%) and a slightly smaller percentage followed by primary care physicians (82.8%) had tried at least one CAM therapy for relief of OA symptoms. The authors suggested that the higher percentage for specialist care may be because these patients have more severe disease and therefore experience more pain.4 An understanding of these therapies will allow primary care and specialist physicians to better communicate with and advise patients who seek options outside the usual spectrum of care.

Definition and therapeutic goals

OA is a progressive deterioration of joint tissues.5 A decrease in protective proteoglycans and collagen compromises joint cartilage.5-8 Deterioration of cartilage in turn leads to bone erosions, osteophyte formation, and bone restructuring. Inflammation, too, may result in reaction to cartilage degradation byproducts entering synovial spaces.6,7 Joint pain aggravated by physical activity and alleviated by rest is typical of OA. Also common are joint instability and stiffness upon rising in the morning or after extended inactivity.9 A patient’s history may additionally reveal that the level of pain experienced with activity has steadily increased with time. Physical examination may reveal bony enlargement or deformity of involved joints, crepitus, and restricted range of motion.9 The value of laboratory and radiology studies lies mainly in ruling out alternative diagnoses.

The goals of OA treatment are pain relief and preservation of joint function. Because the experience of pain is influenced by physical, psychological, and emotional factors, individuals vary in how they respond to specific therapies and in how they wish to achieve pain relief. Some patients may experience side effects from anti-inflammatory pain medications.10 Others may be hesitant to resort to surgery.9 All major guidelines agree that, for most patients, therapy combining nonpharmacologic measures and pharmacologic agents is required to achieve optimal relief of pain and preservation of joint mobility.11-14

Conventional treatment options for OA

Selecting appropriate treatment begins with consideration of the patient’s report of chronic pain and limitations in ambulation or other activities. Also important is assessment of the patient’s level of pain on manipulation, as well as muscle strength and ligament stability.7,8 Depending on physical examination results, a reasonable approach may be to start with nonpharmacologic measures and add pharmacologic agents in a stepwise manner to control pain.8 Self-management programs have been shown to improve symptoms as well as quality of life, and should be incorporated into the treatment plan.15

Nonpharmacologic measures, prescribed as needed for each individual, include weight loss for those who are overweight or obese.11-14 Weight loss has been shown to improve mobility and reduce pain. For every one pound of weight lost, there is a 4-pound reduction in the load exerted on the knee for each step taken during daily activities.16 A weight loss of only 15 pounds can cut knee pain in half for overweight individuals with arthritis.17 A low-carbohydrate diet has been shown to reduce weight in obese patients by ≥10% and lead to improvements in self-reported scores for overall progress and functional ability.18 A diet of fruits and vegetables (including alliums and cruciferous vegetables) that is high in phytonutrients has been shown to have a protective effect in patients with hip OA.19

Other measures are physical and occupational therapies, assistive devices for walking or accomplishing other daily tasks, and joint taping.11-14 Patient (and family) education regarding the progressive nature of OA is crucial to bolstering patient resolve in following through with self-management activities.15 Healthcare professionals can provide factual, disease-specific information on some effective self-management strategies for use between office visits that yield short- and long-term benefits. Self-management strategies can incorporate pain management education; joint-sparing exercise advice including daily walking, balance tips, and falls prevention; and emotional and cognitive skills to improve quality of life.