Epilepsy vs psychogenic nonepileptic seizures

PNES episodes appear similar to epileptic seizures, but without a definitive neurobiologic source.2,3 However, recent literature suggests the root cause may be found in abnormalities in neurologic networks, such as dysfunction of frontal and parietal lobe connectivity and increased communication from emotional centers of the brain.2,5 There are no typical pathognomonic symptoms of PNES, leading to diagnostic difficulty.2 A definitive diagnosis may be made when a patient experiences seizures without EEG abnormalities.2 Further diagnostic brain imaging is unnecessary.

Trauma may be the underlying cause

A predominance of PNES in both women and young adults, with no definitive associated factors, has been reported in the literature.2 Studies suggest childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse, traumatic brain injury, and health-related trauma, such as distressing medical experiences and surgeries, may be risk factors, while depression, misdiagnosis, and mistreatment can heighten seizure activity.2,3

Treatment requires a multidisciplinary team

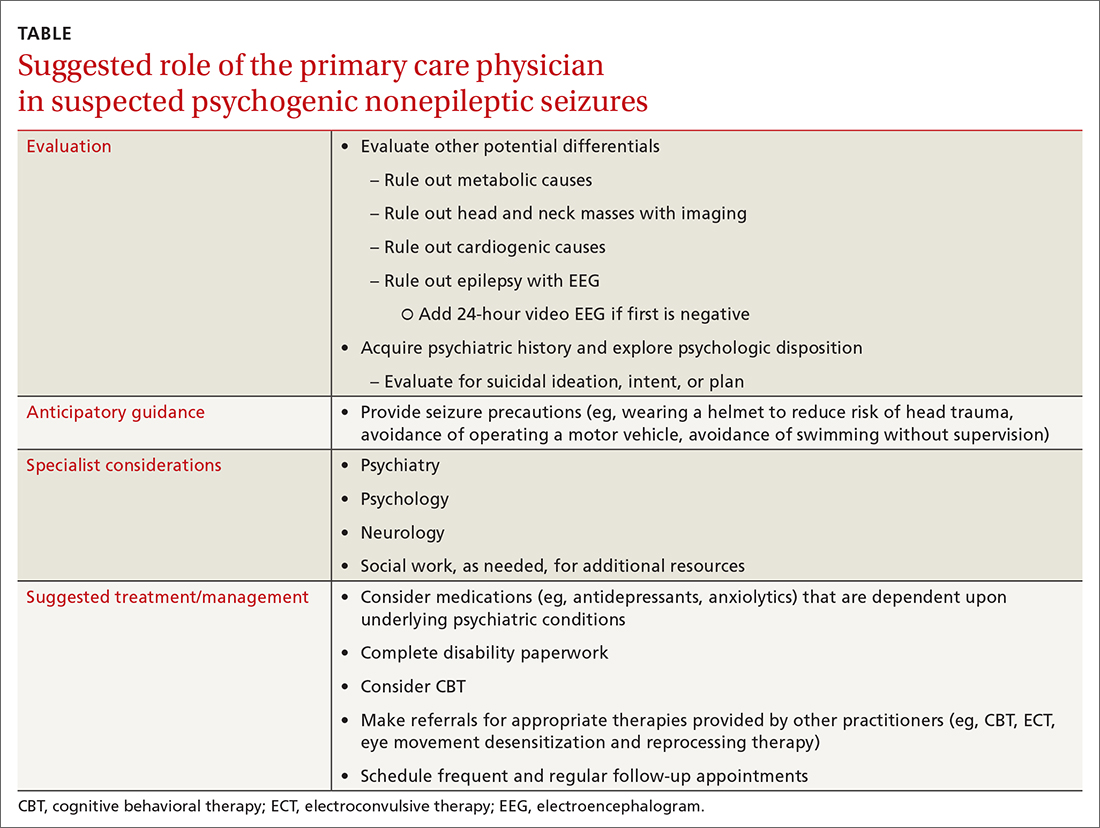

Effective management of PNES requires collaboration between the primary care physician, neurologist, psychiatrist, and psychotherapist, with an emphasis on evaluation and control of the underlying trigger(s).3 Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), supportive care, and patient education in reducing seizure frequency at the 6-month follow-up.3,6 Additional studies have reported the best prognostic factor in PNES management is patient employment of an internal locus of control—the patient’s belief that they control life events.7,8 Case series suggest electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an effective alternative mood stabilization and seizure reduction therapy when tolerated.9

Our patient tried several combinations of treatment to manage PNES and comorbid psychiatric conditions, including CBT, antidepressants, and anxiolytics. After about 5 treatment failures, she pursued ECT for treatment-resistant depression and PNES frequency reduction but failed to tolerate therapy. Currently, her PNES has been reduced to 1 to 2 weekly episodes with a 200 mg/d dose of lamotrigine as a mood stabilizer combined with CBT.

THE TAKEAWAY

Providers should investigate a patient’s history and psychologic disposition when the patient presents with seizure-like behavior without a neurobiologic source or with a negative video-EEG study. A history of depression, traumatic experience, PTSD, or other psychosocial triggers must be noted early to prevent a delay in treatment when PNES is part of the differential. Due to a delayed diagnosis of PNES in our patient, she went without full treatment for almost 12 months and experienced worsening episodes. The primary care physician plays an integral role in early identification and intervention through anticipatory guidance, initial work-up, and support for patients with suspected PNES (TABLE).

CORRESPONDENCE

Karim Hanna, MD, 13330 USF Laurel Drive, Tampa, FL; khanna@usf.edu