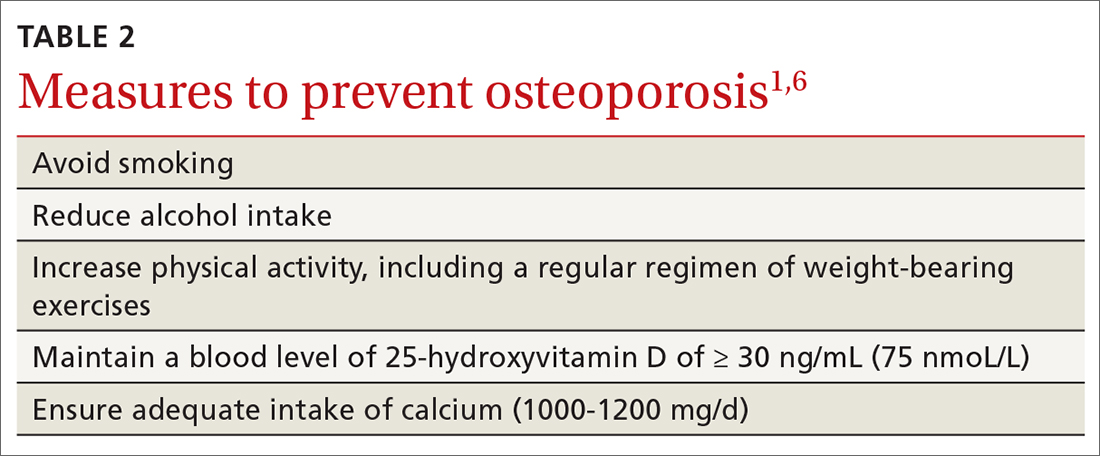

Putting preventive measures into practice

Measures to prevent osteoporosis and preserve bone health (TABLE 21,6) are best started in childhood but can be initiated at any age and maintained through the lifespan. Encourage older adults to adopt dietary and behavioral strategies to improve their bone health and prevent fracture. We recommend the following strategies; take each patient’s individual situation into consideration when electing to adopt any of these measures.

❚ Vitamin D. Consider checking the serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and providing supplementation (800-1000 IU daily, the National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends1) as necessary to maintain the level at 30-50 ng/mL.6

❚ Calcium. Encourage a daily dietary calcium intake of 1000-1200 mg. Supplement calcium if you determine that diet does not provide an adequate amount.

❚ Alcohol. Advise patients to limit consumption to < 3 drinks a day.

❚ Tobacco. Advise smoking cessation.

❚ Activity. Encourage an active lifestyle, including regular weight-bearing and balance exercises and resistance exercises such as Pilates, weightlifting, and tai chi. The regimen should be tailored to the patient’s individual situation.

❚ Medical therapy for concomitant illness. When possible, prescribe medications for chronic comorbidities that can also benefit bone health. For example, long-term use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and thiazide diuretics for hypertension are associated with a slower decline in BMD in some populations.21-23

Tailor treatment to patient’s circumstances

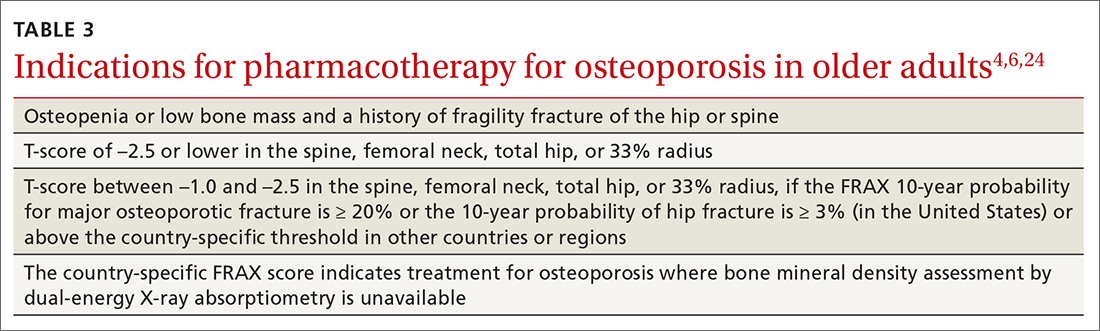

TABLE 34,6,24 describes indications for pharmacotherapy in osteoporosis. Pharmacotherapy is recommended in all cases of osteoporosis and osteopenia when fracture risk is high.24

Generally, you should undertake a discussion with the patient of the relative risks and benefits of treatment, taking into account their values and preferences, to come to a shared decision. Tailoring treatment, based on the patient’s distinctive circumstances, through shared decision-making is key to compliance.25

Pharmacotherapy is not indicated in patients whose risk of fracture is low; however, you should reassess such patients every 2 to 4 years.26 Women with a very high BMD might not need to be retested with DXA any sooner than every 10 to 15 years.

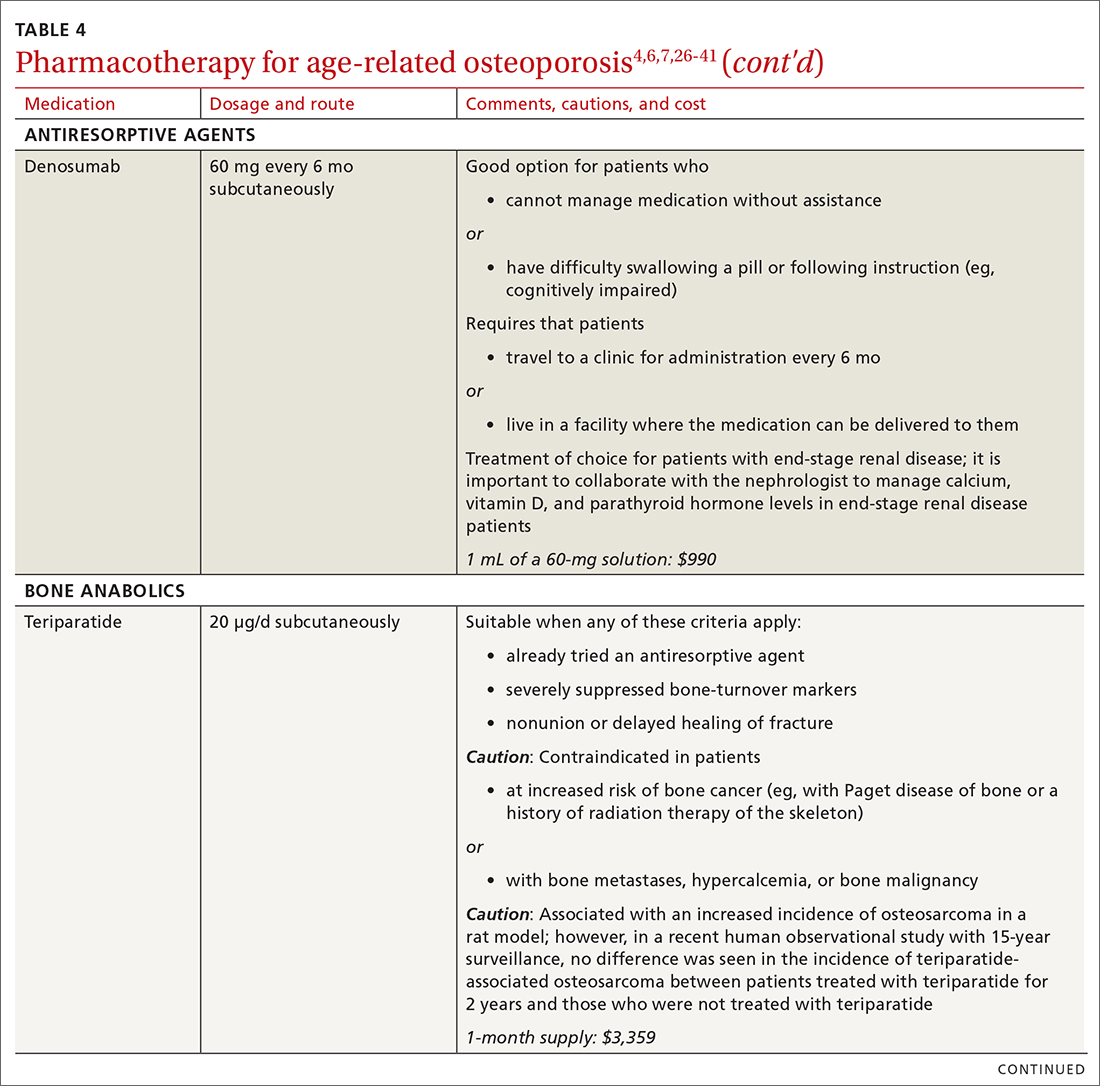

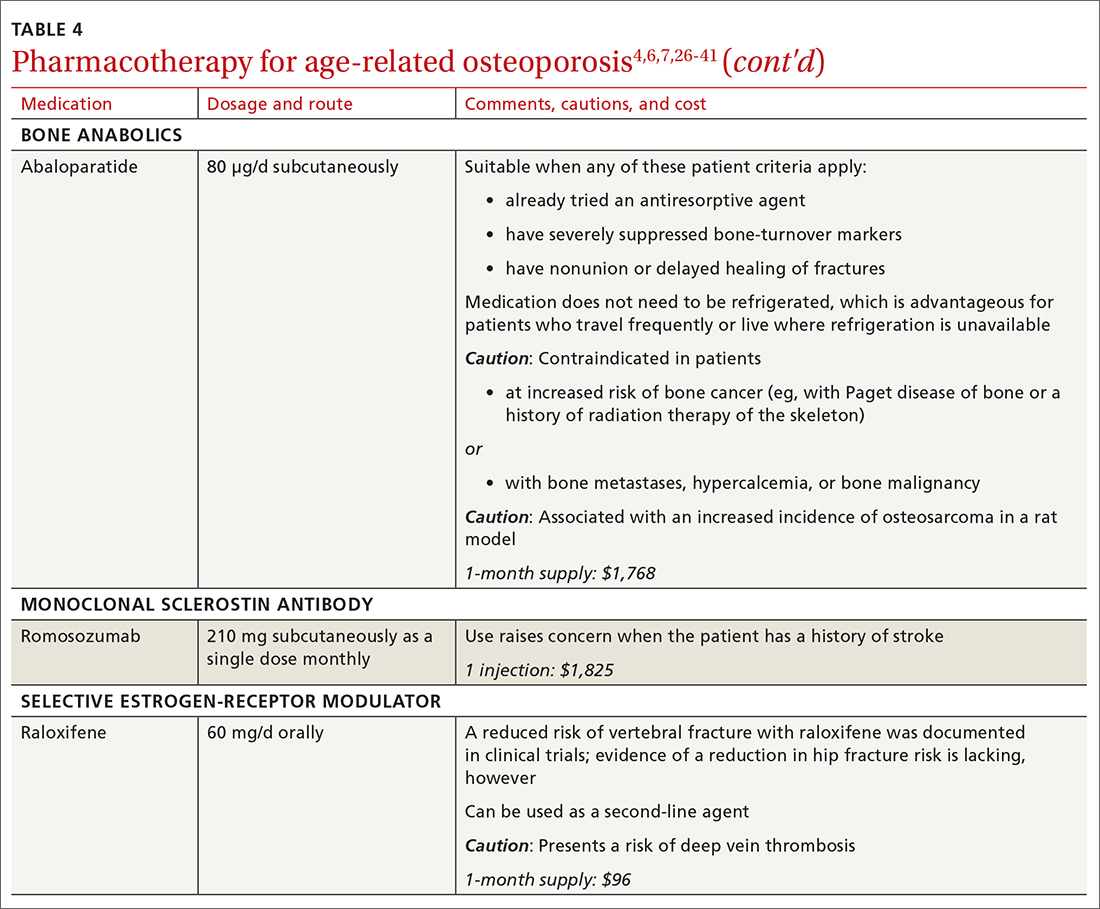

There are 3 main classes of first-line pharmacotherapeutic agents for osteoporosis in older adults (TABLE 44,6,7,26-41): antiresorptives (bisphosphonates and denosumab), anabolics (teriparatide and abaloparatide), and a monoclonal sclerostin antibody (romosozumab). (TABLE 44,6,7,26-41 and the discussion in this section also remark on the selective estrogen-receptor modulator raloxifene, which is used in special clinical circumstances but has been removed from the first line of osteoporosis pharmacotherapy.)

❚ Bisphosphonates. Oral bisphosphonates (alendronate, ibandronate, risedronate) can be used as initial treatment in patients with a high risk of fracture.35 Bisphosphonates have been shown to reduce fracture risk and improve BMD. When an oral bisphosphonate cannot be tolerated, intravenous zoledronate or ibandronate can be used.41

Patients treated with a bisphosphonate should be assessed for their fracture risk after 3 to 5 years of treatment26; when intravenous zoledronate is given as initial therapy, patients should be assessed after 3 years. After assessment, patients who remain at high risk should continue treatment; those whose fracture risk has decreased to low or moderate should have treatment temporarily suspended (bisphosphonate holiday) for as long as 5 years.26 Patients on bisphosphonate holiday should have their fracture risk assessed at 2- to 4-year intervals.26 Restart treatment if there is an increase in fracture risk (eg, a decrease in BMD) or if a fracture occurs. Bisphosphonates have a prolonged effect on BMD—for many years after treatment is discontinued.27,28

Oral bisphosphonates are associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease, difficulty swallowing, and gastritis. Rare adverse effects include osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femur fracture.29

❚ Denosumab, a recombinant human antibody, is a relatively newer antiresorptive for initial treatment. Denosumab, 60 mg, is given subcutaneously every 6 months. The drug can be used when bisphosphonates are contraindicated, the patient finds the bisphosphonate dosing regimen difficult to follow, or the patient is unresponsive to bisphosphonates.

Patients taking denosumab are reassessed every 5 to 10 years to determine whether to continue therapy or change to a new drug. Abrupt discontinuation of therapy can lead to rebound bone loss and increased risk of fracture.30-32 As with bisphosphonates, long-term use can be associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femur fracture.33

There is no recommendation for a drug holiday for denosumab. An increase in, or no loss of, bone density and no new fractures while being treated are signs of effective treatment. There is no guideline for stopping denosumab, unless the patient develops adverse effects.

❚ Bone anabolics. Patients with a very high risk of fracture (eg, who have sustained multiple vertebral fractures), can begin treatment with teriparatide (20 μg/d subcutaneously) or abaloparatide (80 μg/d subcutaneously) for as long as 2 years, followed by treatment with an antiresorptive, such as a bisphosphonate.4,6 Teriparatide can be used in patients who have not responded to an antiresorptive as first-line treatment.

Both abaloparatide and teriparatide might be associated with a risk of osteosarcoma and are contraindicated in patients who are at increased risk of osteosarcoma.36,39,40

❚ Romosozumab, a monoclonal sclerostin antibody, can be used in patients with very high risk of fracture or with multiple vertebral fractures. Romosozumab increases bone formation and reduces bone resorption. It is given monthly, 210 mg subcutaneously, for 1 year. The recommendation is that patients who have completed a course of romosozumab continue with antiresorptive treatment.26

Romosozumab is associated with an increase in the risk of cardiovascular disease, including stroke and myocardial infarction.26

❚ Raloxifene, a selective estrogen-receptor modulator, is no longer a first-line agent for osteoporosis in older adults34 because of its association with an increased risk of deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and lethal stroke. However, raloxifene can be used, at 60 mg/d, when bisphosphonates or denosumab are unsuitable. In addition, raloxifene is particularly useful in women with a high risk of breast cancer and in men who are taking a long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist for prostate cancer.37,38

Continue to: Influence of chronic...