Skin and soft-tissue infections, frequently encountered in primary care, range from the uncomplicated erysipelas to the life-threatening necrotizing fasciitis. This review draws from the latest evidence and guidelines to help guide the care you provide to patients with cellulitis, orbital cellulitis, erysipelas, folliculitis, furuncles, carbuncles, abscesses, and necrotizing fasciitis.

Cellulitis

Cellulitis, an infection of the deep dermal and subcutaneous layers of the skin, has become increasingly common in recent years, with both incidence and hospitalization rates rising.1 Cellulitis occurs when pathogens enter the dermis through breaks in the skin barrier due to cutaneous fungal infections, trauma, pressure sores, venous stasis, or inflammation. The diagnosis is often made clinically based on characteristic skin findings—classically an acute, poorly demarcated area of erythema, warmth, swelling, and tenderness. Lymphangitic streaking and local lymphadenopathy may also be present. Infection often occurs on an extremity (although it can be found on other areas of the body) and is usually unilateral. Fever may or may not be present.2

Likely responsible microorganisms. Staphylococcus aureus and Group A streptococci (often Streptococcus pyogenes) are common culprits. One systematic review that examined cultures taken of intact skin in cellulitis patients found S aureus to be about twice as common as S pyogenes, with both bacteria accounting for a little more than 70% of cases. Of the remaining positive cultures, the most common organisms were alpha-hemolytic streptococcus, group B streptococcus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Clostridium perfringens, Escherichia coli, Pasteurella multocida, and Proteus mirabilis.3 Similarly, a systematic review of bacteremia in patients with cellulitis and erysipelas found that S pyogenes, other beta-hemolytic strep, and S aureus account for about 70% of cases (although S aureus was responsible for just 14%), with the remainder of cases caused by gram-negative organisms such as E coli and P aeruginosa.4

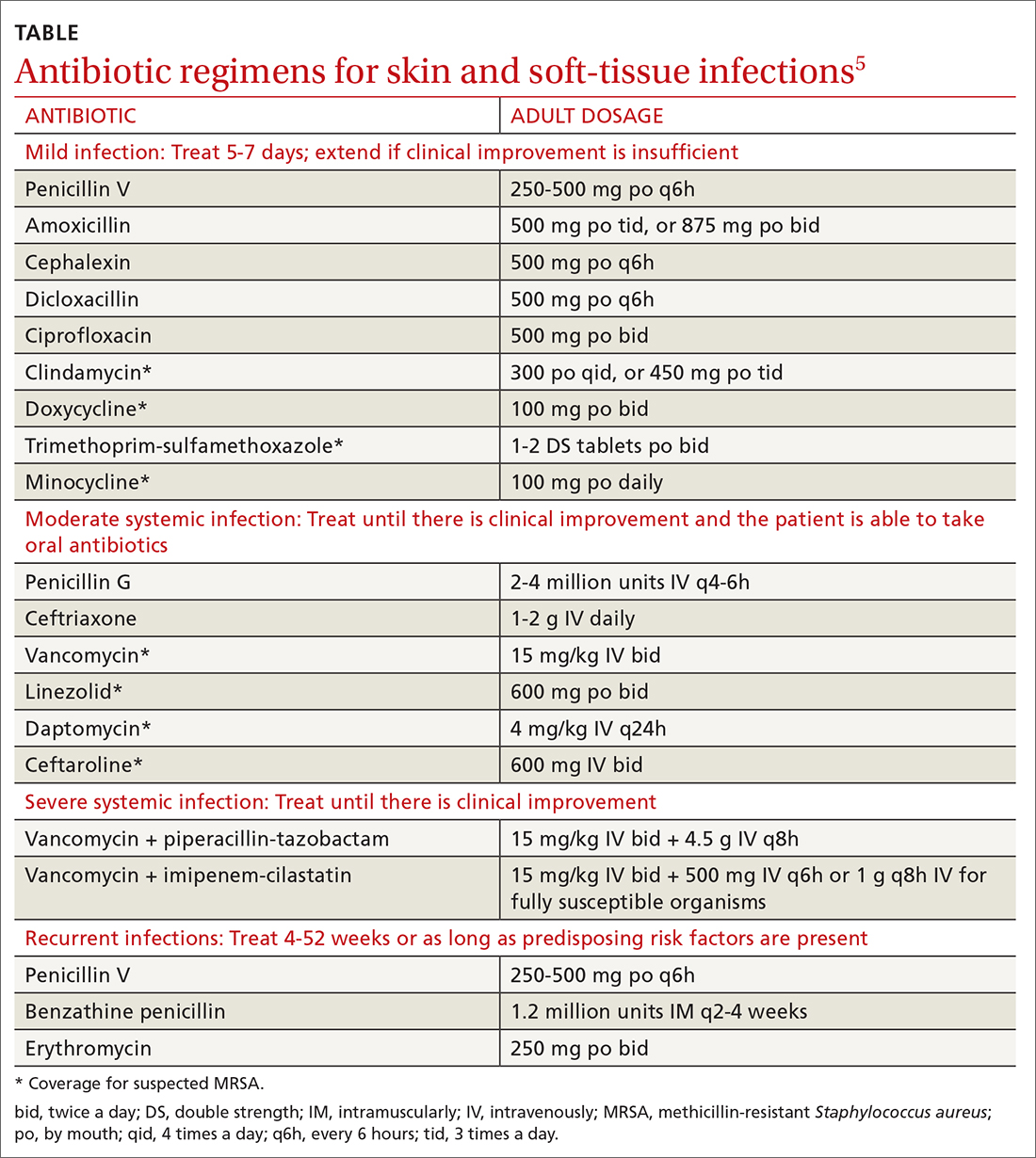

Treatment considerations. Strict treatment guidelines for cellulitis are lacking, but general consensus encourages the use of antibiotics and occasionally surgery. For mild and moderate cases of cellulitis, prescribe oral and parenteral antibiotics to cover for streptococci and methicillin-susceptible S aureus, respectively. Expand coverage to include vancomycin if nasal colonization shows methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) or if you otherwise suspect prior MRSA exposure. Expanded coverage will also be needed if there is severe nonpurulent infection associated with penetrating trauma or a history of intravenous drug use, or the patient meets criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome. If patients are severely compromised (eg, neutropenic), it is reasonable to further add broad-spectrum coverage (eg, intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam or carbapenem). Typical duration of treatment is 5 to 7 days, although this should be extended if there is no clinical improvement.

Generally, cellulitis can be managed in the outpatient setting, although hospitalization is recommended if there are concerns for deep or necrotizing infection, if patients are nonadherent to therapy or are immunocompromised, or if outpatient therapy has failed.5 Furthermore, in an observational study of 606 adult patients, prior episodes of cellulitis, venous insufficiency, and immunosuppression were all independently associated with poorer clinical outcomes.2 Also treat underlying predisposing factors such as edema, obesity, eczema, venous insufficiency, and toe web abnormalities such as fissures, scaling, or maceration.5 Consider the use of prophylactic antibiotics for patients who have had 3 to 4 episodes of cellulitis despite attempts to treat predisposing conditions. Prophylactic antibiotic regimens include penicillin or erythromycin orally and penicillin G benzathine intramuscularly.5 Antibiotic regimens are summarized in the TABLE.5

Orbital cellulitis

Orbital cellulitis is an infection of the tissues posterior to the orbital septum.6,7 Periorbital, or preseptal, cellulitis occurs anterior to the orbital septum and is the more common of the 2 infections—84% compared with 16% for orbital cellulitis.6 However, orbital cellulitis, which affects mainly children at a median age of 7 years,6 must be detected and treated early due to the potential for serious complications such as cavernous sinus thrombosis, meningitis, intracranial abscess, and vision loss.7 Chemosis (conjunctival edema) and diplopia are more commonly associated with orbital cellulitis and are seldom seen with preseptal cellulitis.

Predominant causative organisms are S pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis, non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae, and group A streptococcus. The most common mechanism of infection is tracking from periorbital structures (eg, paranasal and ethmoid sinusitis). Other causes include orbital trauma/fracture, periorbital surgery, and bacterial endocarditis. Clinically, patients present with limited ocular motility and proptosis associated with inflamed conjunctiva, orbital pain, headache, malaise, fever, eyelid edema, and possible decrease in visual acuity. The diagnosis is often made clinically and confirmed with orbital computed tomography (CT) with contrast, which can assist in ruling out intracranial involvement such as abscess.

Continue to: Antibiotic therapy