Patients with previous VTE. Multiple aspects of a patient’s past medical history need to be taken into account when estimating annual and acute risk for VTE. Patients at the highest risk for VTE recurrence (annual VTE risk ≥10%) include those with recent VTE (past 90 days), active malignancy, and/or severe thrombophilias (TABLE 13,5,6,9-11).3,5,6 Patients without any of these features can still be at moderate risk for recurrent VTE, as a single VTE without a clear provoking factor can confer a 5% to 10% annualized risk for recurrence.12,13 Previous proximal DVT and PE are associated with a higher risk for recurrence than a distal DVT, and males have a higher recurrence risk than females.5,12 There are scoring tools, such as DASH (D-dimer, Age, Sex, Hormones) and the “Men Continue and HERDOO2,” that can help estimate annualized risk for VTE recurrence; however, they are not validated (nor particularly useful) when making decisions in the perioperative period.14,15

Additional risk factors. Consider additional risk factors for thromboembolism, including estrogen/hormone replacement therapy, pregnancy, leg or hip fractures, immobility, trauma, spinal cord injury, central venous lines, congestive heart failure, thrombophilia, increased age, obesity, and varicose veins.5,16

In addition, some surgeries have a higher inherent risk for thrombosis. Major orthopedic surgery (knee and hip arthroplasty, hip fracture surgery) and surgeries for major trauma or spinal cord injuries are associated with an exceedingly high rate of VTE.17 Similarly, coronary artery bypass surgery, heart valve replacement, and carotid endarterectomies carry the highest risk for acute ischemic stroke.3

Who’s at highest risk for bleeding?

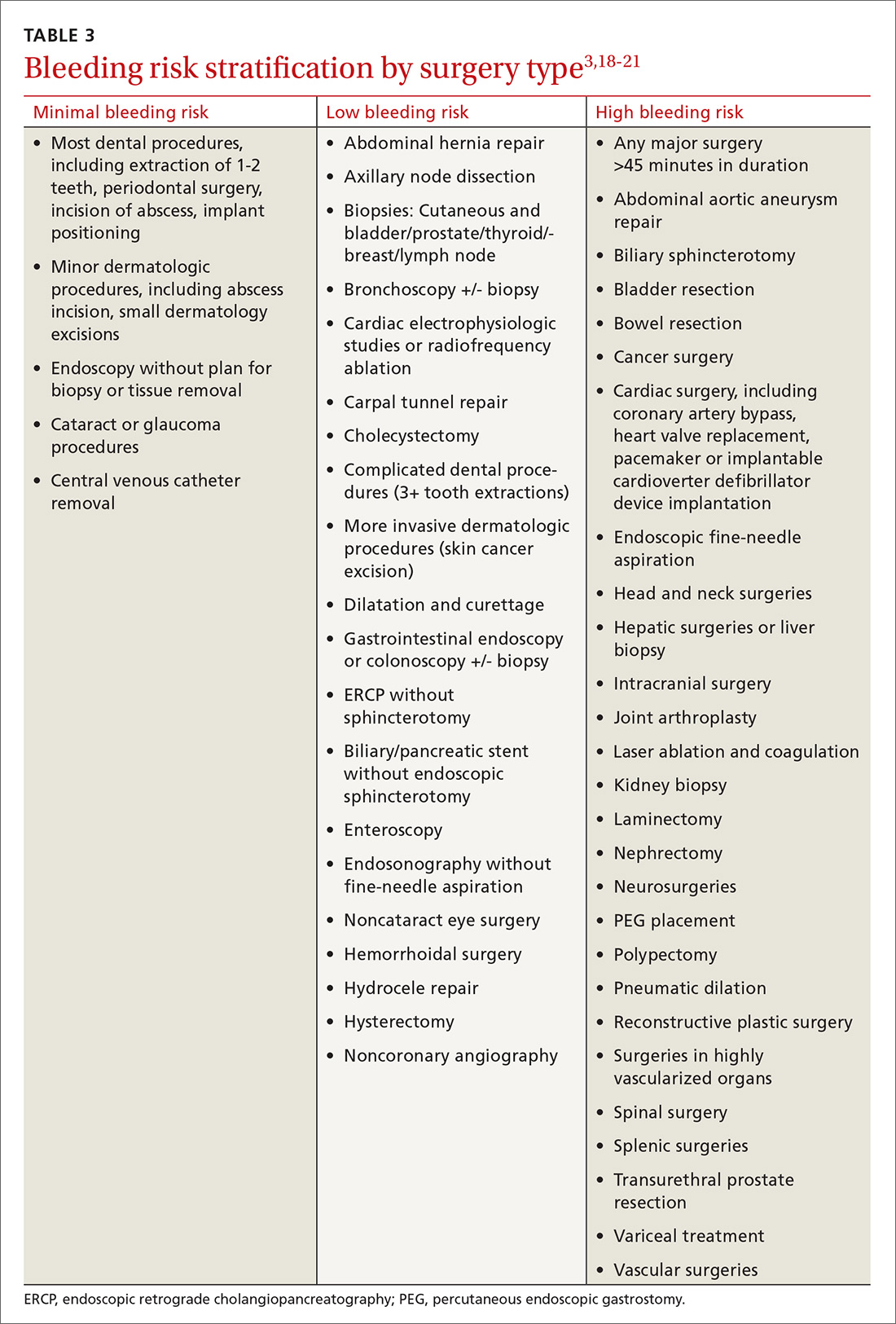

Establishing the bleeding risk associated with a procedure is imperative prior to urgent and elective surgeries to help determine when anticoagulation therapy should be discontinued and reinitiated, as well as whether bridging therapy is appropriate. The 2012 CHEST guidelines state that bleeding risk should be assessed based on timing of anticoagulation relative to surgery and whether the anticoagulation is being used as prophylaxis for, or treatment of, thromboembolism.3 Categorizing procedures as having a minimal, low, or high risk for bleeding can be helpful in making anticoagulation decisions (TABLE 3).3,18-21

In addition to the bleeding risk associated with procedures, patient-specific factors need to be considered. A bleeding event within the past 3 months, platelet abnormalities, a supratherapeutic INR at the time of surgery, a history of bleeding from previous bridging, a bleed history with a similar procedure, and a high HAS-BLED (Hypertension, Abnormal renal or liver function, Stroke, Bleeding history or predisposition, Labile INR, Elderly, Drugs/alcohol usage) score are all factors that elevate the risk for perioperative bleeding.10,11 Although validated only in patients taking warfarin, the HAS-BLED scoring system can be utilized in patients with AF to estimate annual risk for major bleeding (TABLE 210,11).10

With this risk information in mind, it’s time to move on to the 5 questions you’ll need to ask.

1. Should the patient’s oral anticoagulation be stopped prior to the upcoming procedure?

The answer, of course, hinges on the patient’s risk of bleeding.

Usually, it is not necessary to withhold any doses of oral anticoagulation if your patient is scheduled for a procedure with minimal risk for bleeding (TABLE 33,18-21).3 However, it may be reasonable to stop anticoagulation if your patient has additional features that predispose to high bleeding risk (eg, hemophilia, Von Willebrand disease, etc). The CHEST guidelines recommend adding an oral prohemostatic agent (eg, tranexamic acid) if anticoagulation will be continued during a dental procedure.3

If your patient is undergoing any other procedure that has a low to high risk for bleeding, oral anticoagulation should be withheld prior to the procedure in most instances,3,11 although there are exceptions. For example, cardiac procedures, such as AF catheter ablation and cardiac pacemaker placement, are often performed with uninterrupted oral anticoagulation despite their bleeding risk category.3

When in doubt, discuss the perceived bleeding and clotting risks directly with the specialist performing the procedure. In patients who have had a VTE or ischemic stroke within the past 3 months, consider postponing the invasive procedure until the patient is beyond this period of highest thrombotic risk.11