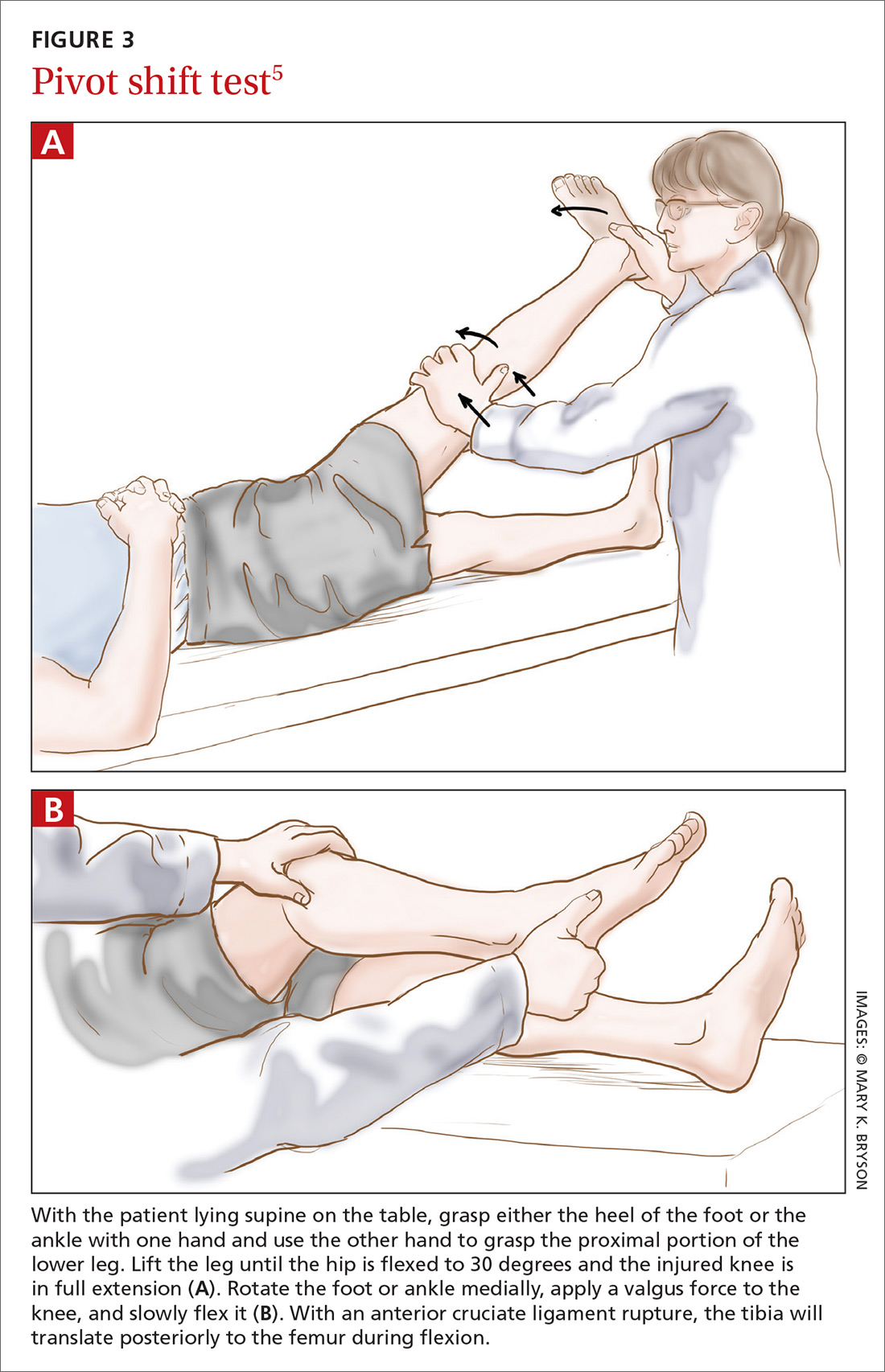

Pivot shift test

How it’s done. With the patient lying supine on the table, the examiner uses one hand to hold the patient’s heel or ankle and the other hand to grasp the proximal portion of the lower leg (FIGURE 3).5 Lifting the leg to about 30 degrees from the table with the injured knee in full extension, the examiner rotates the foot or ankle medially, applies a valgus force to the knee, and slowly flexes it. During flexion, a ruptured ACL will cause the tibia to translate posteriorly to the femur. (Note that the starting position of the test has the tibia subluxed anteriorly. The posterior translation is the "pivot shift" back into the neutral position.)

The literature. The pivot shift test is technically more challenging to perform than the other 2 tests and is, therefore, less practical in the primary care setting. However, when this test is done correctly, a positive result is highly specific for ACL injury.9,10 Reported sensitivity values are contradictory. The most recent meta-analysis reports a sensitivity of 85%.6 Two other studies cite much lower values: 24% and 28%.9,10 These data suggest that the pivot shift test, when carried out correctly, can be of use in confirming a possible ACL rupture. However, the test should not be used alone in ruling out a possible ACL injury.

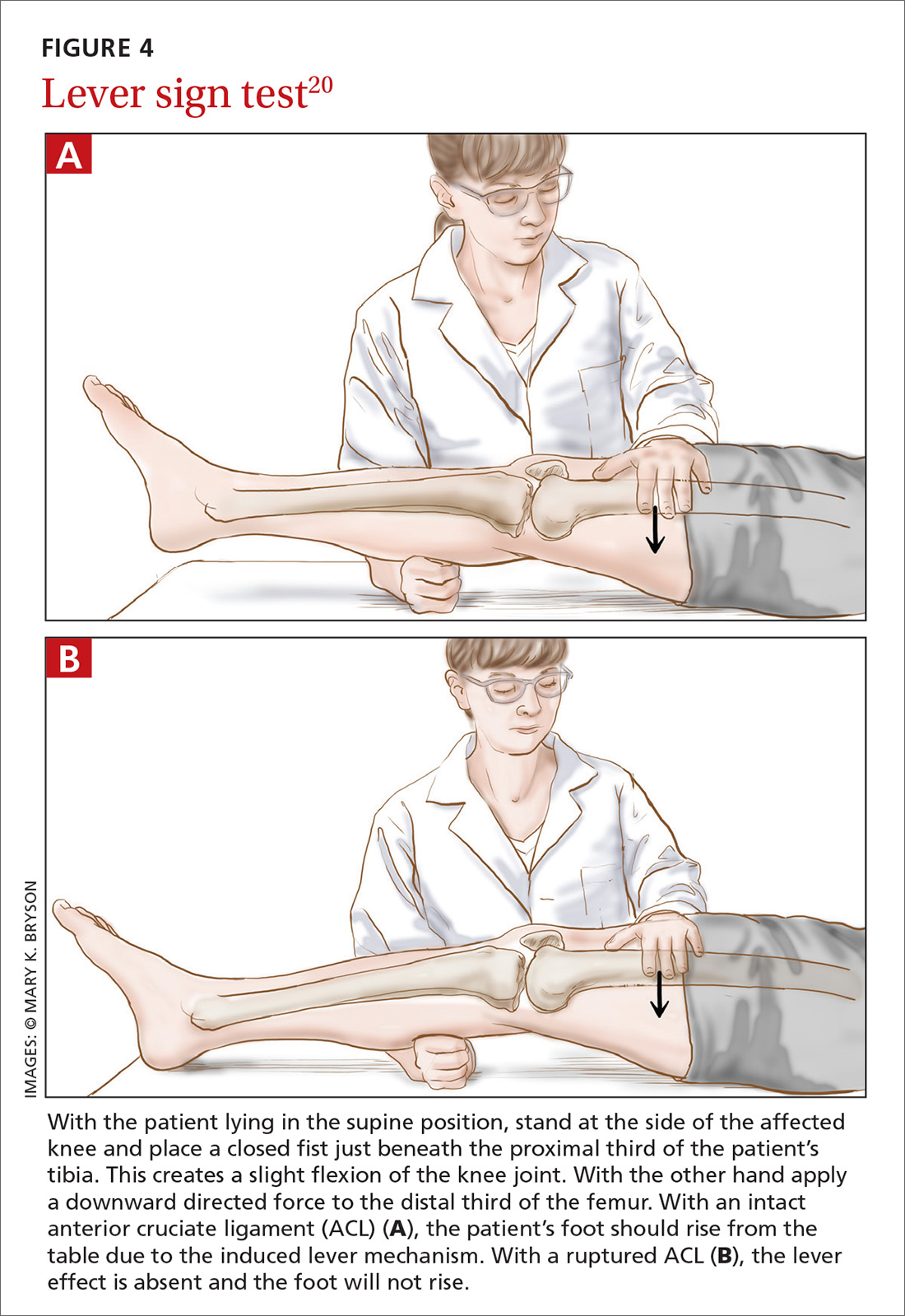

New diagnostic test: Lever sign test

How it’s done. The lever sign test (FIGURE 4),20 introduced in the mid-2010s, is also performed with the patient lying in the supine position. The examiner stands at the side of the affected knee of the patient, places a closed fist just beneath the proximal third of the patient’s tibia, creating a slight flexion of the knee joint. With the other hand, the examiner applies a downward directed force to the distal third of the femur. With an intact ACL, the patient’s foot should rise from the table due to the induced lever mechanism. With a ruptured ACL, the lever effect is absent and the foot will not rise.

The literature. In the prospective clinical study that introduced the lever sign test, the sensitivity rate was reported at 100%—higher than that seen with the other commonly used tests.20 Another study has reported that the lever sign test was easily adopted in clinical practice and showed higher sensitivity than the Lachman test (94% vs 80% in pre-anesthesia assessment).21 However, a more recent study has shown a sensitivity of 77% for the lever sign.22 The lever sign test is relatively easy to perform and requires less examiner strength than does the Lachman test. These factors enhance applicability of the lever sign test in the primary care office and in other settings such as physical therapy centers and emergency departments.

Applying this information in primary care

Given the importance of physical examination in diagnosing ACL injury, how can the current evidence best be applied in primary care practice? Based on its good test properties and feasibility, the Lachman test is preferred in primary care. The anterior drawer test can be used, but its low accuracy must be considered in making an assessment. The pivot shift test, given its difficulty of execution, should not be used by physicians unacquainted with it.

If future research supports early reports of the lever sign test’s accuracy, it could be very helpful in family practice. Going forward, research should aim at developing a constructive strategy for applying these physical examination tests in both primary care and specialty settings.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christiaan H. Koster, Department of Trauma Surgery, VU University Medical Centre, P.O. Box 7057, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands; c.koster@vumc.nl.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Frits Oosterveld, PhD, for critically reviewing the manuscript and Ralph de Vries for his assistance in the literature search.