Sleep logs can present a powerful picture

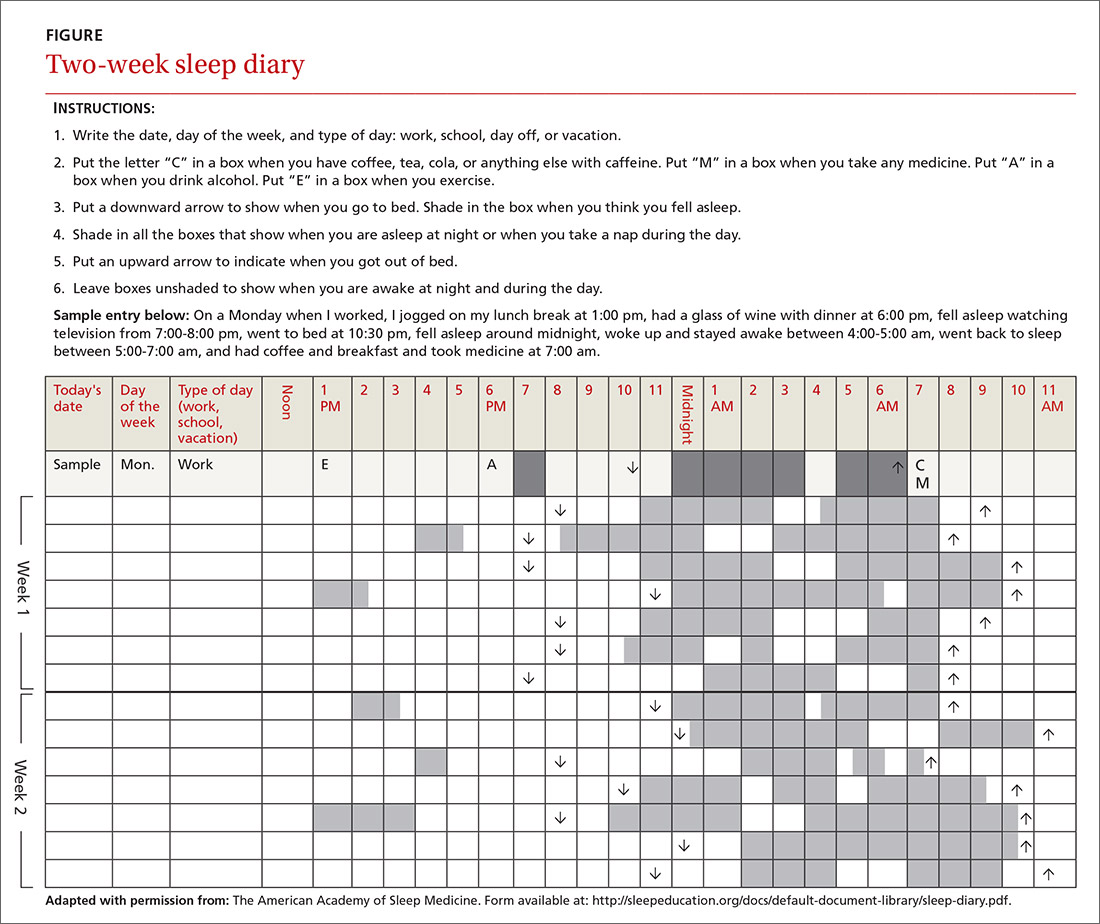

In addition to a history and physical exam, physicians should ask their patients with chronic insomnia to complete sleep logs for 2 to 3 weeks.20 A sleep log with midnight near the middle of the page is preferred by many because it places the typical sleeping hours in the middle of the page, showing relevant information in a way that can be grasped immediately (FIGURE 1). To save time, nurses can provide sleep logs to patients along with instructions about how to complete them.

Patient-completed sleep logs often illuminate obvious detrimental behaviors that reinforce insomnia (eg, spending excessive time in bed, having irregular bed/wake times, daytime napping that diminishes sleep drive in the evening). In addition, they sometimes reveal circadian rhythm abnormalities such as delayed sleep phase syndrome in which the patient attempts to sleep at a normal bedtime, but exhibits a marked delay in falling asleep/waking up compared to societal norms. Seeing such information graphically represented is often a powerful learning experience for both physician and patient.

Sleep studies aren't usually warranted

In its most recent (2008) clinical guideline on the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) stated that “routine testing in the sleep lab is not warranted for most cases of insomnia.” Instead, it is reserved for individuals in whom there is a suspicion of a comorbid sleep disorder. FPs should refer patients for formal sleep studies only if, in addition to the insomnia complaint, there is suspicion of:20

- obstructive sleep apnea (based upon some combination of loud snoring, obesity, hypertension, and/or excessive daytime sleepiness),

- narcolepsy (based upon excessive daytime sleepiness without a readily identifiable cause), or

- arousals with the potential for self-injurious behavior (parasomnias).

Treatments: Sleep hygiene, CBT-I, and medication

Sleep hygiene, cognitive/behavioral techniques, and pharmacotherapy serve as the core of therapy for chronic insomnia.

Sleep hygiene: Common-sense strategies

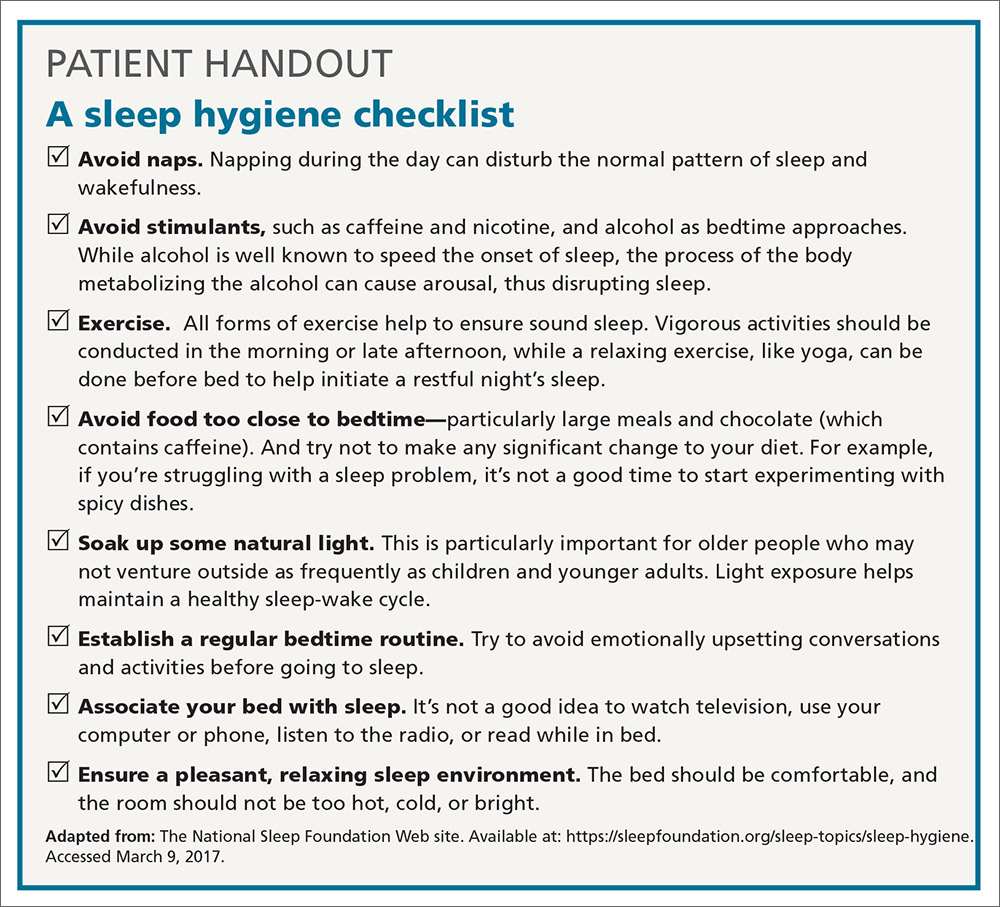

Most FPs are familiar with sleep hygiene instructions; these are simple, common-sense behavioral techniques such as limiting caffeine and screen (television, computer) time at night, avoiding daytime naps, and maintaining regular bed- and out-of-bed times. (See “A sleep hygiene checklist.”) Although it is a logical starting point for behavioral modification, sleep hygiene has not been studied rigorously as a monotherapy for insomnia and, therefore, doesn’t have an evidence rating in terms of effectiveness.20

CBT-I: Treatment of choice

CBT-I seeks to lower cognitive and somatic arousal. Taken together, cognitive and behavioral techniques are effective in 70% to 80% of people, whether they have primary insomnia or comorbidities.25-27 Furthermore, the benefits are sustained with the passage of time.27 CBT-I is regarded as the treatment of choice for chronic insomnia.20

When provided by a highly trained mental health professional, CBT-I usually takes the form of a series of 6 to 8 weekly appointments. Descriptions and manuals for CBT-I abound and online programs have also proliferated.28,29 However, there is a shortage of highly trained providers, and most FPs do not feel proficient to engage fully in CBT-I.8,9 Nevertheless, some behavioral elements of CBT-I, such as stimulus control and sleep restriction, can be utilized in the family medicine setting and may be effective for a significant subset of patients.

Stimulus control and sleep restriction. Two behavioral techniques for insomnia that can be applied in the family medicine setting are stimulus control and sleep restriction therapy.20

With stimulus control, patients attempt to eliminate stimuli that weaken the psychological association between the bed and successful sleep, namely wakeful activities in bed such as watching television, reading, or even “tossing and turning.” Instead, they are instructed to use their bed only for sleep (and intimacy), to vacate it if awake and not clearly on the verge of sleep, and to avoid looking at a clock during the night. Patients are also advised to sleep only in their own bed and not in other places in their home.

Sleep restriction is predicated on the observation that many people with insomnia habitually spend too much time awake in bed, and this creates a conditioned arousal response to the bed. With sleep restriction, the patient is assigned a narrow window of “allowed time in bed,” usually a 6-hour interval of their choosing, and is instructed to adhere to this schedule for a period of 2 to 4 weeks. Many patients find that they fall asleep more rapidly and stay asleep longer after a few weeks. This experience of “successful” sleep initiation and maintenance is important psychologically; it renews their confidence in their ability to sleep, which is missing in most people with chronic insomnia.

If you use this approach with a patient, be sure to acknowledge that sleep restriction usually engenders some sleep deprivation in the first few weeks. But it is only a short-term intervention designed to change the expectation of nightly insomnia that is so ingrained in these patients. While they engage in sleep restriction, patients should keep sleep logs to track their “sleep efficiency” (ie, estimated time asleep vs time in bed). Once good sleep efficiency (>85%) is achieved, they may gradually lengthen their allowed time in bed by 15 minutes each week until they are obtaining 7 to 9 hours of sleep per night. (See “Breaking the cycle of insomnia by employing sleep restriction.”)

SIDEBAR

Breaking the cycle of insomnia by employing sleep restrictionExplain to patients: “Your sleep logs indicate that you get only 3 to 4 hours of sleep per night in total despite being in bed for 8 to 9 hours. I recommend a trial of 'sleep restriction' to increase the proportion of time spent sleeping to overall time in bed. This often helps to break the pattern of insomnia.”

1. Choose a 6-hour interval. The start time is the time you’ll go to bed each night and the end time is the time you’ll get up. Although this might seem like a drastic reduction in the time that you make for sleep, it is still more time than you are presently spending asleep.

2. Get out of bed and conduct a quiet activity—such as reading—if you find that you are wide awake during the 6-hour interval. Return to your bed only if/when you feel drowsy.

3. Continue to complete sleep logs. If you are consistently asleep 85% of the total time in bed, then you can expand your allowed time in bed by 15 minutes (earlier bedtime or later out-of-bed time) each week.