Routine screening for type 1 diabetes among healthy children is not expected to yield many cases and is not recommended. However, because the incidence of type 2 diabetes is increasing among children, it has been suggested that those who are overweight (defined as weight for height >85th percentile or weight >120% of ideal for height) with 2 or more additional risk factors should be screened every 2 years, beginning at age 10 years or at the onset of puberty.19

The ADA criteria for diagnosis of diabetes are listed in Table 1 . Whichever criterion is used, diagnostic test results must be confirmed on a subsequent day.19

Patients who do not meet the diagnostic criteria but have either impaired fasting glucose (IFG) or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) are considered to have prediabetes (see Table 1 ).19,21 Based on recent estimates, more than 12 million adults in the United States have prediabetes.22 Of great importance is regular monitoring of patients with IGT or IFG because in addition to diabetes, they are at a heightened risk of MI or stroke compared with normoglycemic persons.

TABLE 1

Diagnostic criteria for prediabetes and diabetes

| Prediabetes | Diabetes |

|---|---|

| One or both of the following: | One or more of the following: |

|

|

| *Oral glucose tolerance test should use glucose load containing equivalent of 75 g anhydrous glucose dissolved in water. | |

| Adapted from American Diabetes Association.19 | |

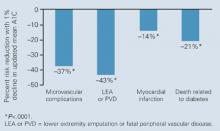

Intensive management

The UKPDS showed that intensive glycemic control in type 2 diabetes significantly reduced the risk of microvascular complications.23,24 In UKPDS 33, patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes whose disease remained uncontrolled after completing 3 months of dietary management were initially randomized to intensive treatment (goal: FPG <108 mg/dL) with sulfonylurea or insulin monotherapy or to conventional treatment (goal: FPG <270 mg/dL) that began with diet. After 10 years, the median A1C was 7.0% in the intensive group and 7.9% in the conventional group.23 The reduction in A1C was associated with a 25% reduction of microvascular endpoints, mainly a reduced need for retinal photocoagulation (relative risk [RR] for intensive therapy, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.60–0.93; P<.01). While there was a 16% reduction in the risk of MI, this difference was not statistically significant (RR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.71–1.00; P=.052). The UKPDS 35, which was an epidemiologic analysis of data (ie, not a direct comparison of the 2 treatment arms), demonstrated that each 1% reduction in mean A1C was associated with a 21% decrease in risk for any diabetes-related endpoint (95% CI, 17%–24%; P<.0001), a 21% decrease in diabetes-related deaths (95% CI, 15%–27%; P<.0001), a 37% decrease in the risk for microvascular complications (95% CI, 33%–41%; P<.0001), and a 14% decrease in the risk of MI (95% CI, 8%–21%; P<.0001) ( Figure 1 ).6

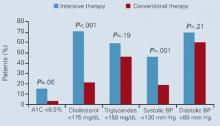

Another study that supports intensive management of type 2 diabetes is the Steno-2 study, a randomized controlled trial of 160 patients with type 2 diabetes and microalbuminuria.8 After 7.8 years of follow-up, 54% of conventionally treated and 57% of intensively treated patients were receiving insulin. Decreases in risk factors (eg, A1C, blood pressure, lipids, and albumin excretion) were significantly greater in patients receiving intensive therapy ( Figure 2 ). Significant reductions also were seen in the risk of cardiovascular disease (RR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.24–0.73), nephropathy (RR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.17–0.87), retinopathy (RR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.21–0.86), and autonomic neuropathy (RR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.18–0.79). Overall, intensive therapy in the Steno-2 study reduced risk of cardiovascular and microvascular events by about 50%.

FIGURE 1

UKPDS 35: Risk reductions associated with each 1% decrease in updated mean A1C

FIGURE 2 Percentage of patients in Steno-2 who reached treatment goals at mean follow-up of 7.8 years

Role of insulin in achieving targets

Another finding of the UKPDS was that type 2 diabetes is routinely progressive and that treatment with a single agent is unlikely to be successful for more than 5 years. Such observations mirror the physiologic progression from insulin resistance to absolute insulin deficiency. Thus, lifestyle modification often needs to be supplemented with oral antihyperglycemic therapy. In some cases, early treatment with insulin is preferable to relieve symptoms of hyperglycemia (eg, blurred vision, frequent thirst), which are suggestive of glucotoxicity and deteriorating β-cell function. As absolute insulin deficiency occurs, multiple oral agents, with or without insulin, may be required for optimal control of the disease.4,25