Discussion

The patient’s chief complaint of lower extremity muscle weakness was a clinical emergency that merited thorough investigation in a timely manner to preserve limb function. Since her medical history did not provide pathologic insight concerning her condition, physical examination by emergency personnel served as the founding evidence for this patient’s diagnosis. Decreased muscle tone of the lower extremities and rectal sphincter raised suspicion for a neurological etiology. These symptoms, along with hyperreflexia, the presence of a Babinski sign, and dual-system incontinence, were suggestive of an underlying central nervous system lesion. Of note, urinary complaints commonly result from retention leading to overflow incontinence, a time-dependent symptom that may not be experienced before presentation to medical personnel. Urinary retention is one of the most consistent findings in patients with CMS and SCC, with a relative prevalence of 90%.4,7,8

For providers not familiar with CMS presentation, preserved tactile sensation, normoreflexia, and lack of a Babinski sign and/or incontinence are not sufficient indicators to discontinue the consideration of spinal cord lesions in the differential diagnosis and may in fact be misleading.6,9,10 Although the patient’s deficits were not symmetrical as is commonly reported, this did not rule out the diagnosis.

Appropriate diagnosis and treatment of such a rare entity in the emergency setting consists of a high clinical suspicion, MRI of the spine, urgent consultations, and early treatment with parenteral corticosteroids.3,4 The patient did not have a previous diagnosis of breast carcinoma; however, once discovered on examination, the condition became suspect as approximately 80% of patients with SCC have a preexisting cancer. The peak incidence of SCC is in the sixth and seventh decades of life. The most common primary cancers metastasizing to bone are breast, prostate, and lung. When found to affect the spine, roughly 60% will be located in the thoracic spine, 30% at the lumbosacral level, and 10% in the cervical spine.

As demonstrated in this case presentation, a thorough examination cannot be stressed enough in emergent situations. The patient’s dermatological findings and nontender lymphadenopathy were adequately significant to consider the possibility of a metastatic process as the underlying etiology. Although discouraged due to the fast-paced environment of the ED, patients are frequently assessed and examined in street clothing, which in this case, may have masked the underlying cause of the patient’s neurological deficits. As a result, imaging studies, corticosteroid treatment, consultations, and surgical management may have been delayed, leading to a nonreversible outcome for the patient.

Central and Peripheral Nervous System Structures and Deficits

Central and peripheral nervous system structures animate the body through coordinated signaling of upper and lower motor neurons respectively. In most adults, the distal spinal cord terminates at the level of the first or second lumbar vertebrae where the conus medullaris is found, giving rise to S2, S3 and S4 functionality. Lesions at this level exhibit lower motor neuron deficits of the bladder and rectum resulting in incontinence and sexual dysfunction. Deficits of sensorium such as saddle anesthesia or upper motor neuron lesions as evidenced by increased motor tone and abnormal reflexes are not uncommon.1 Branches of the cauda equina extend caudally from the epiconus, a structure proximal to the conus medullaris, as peripheral nervous system branches that innervate spinal cord segments L4 through S1 (Figure 2). Lesions of the epiconus are clinically distinguished by lower motor neuron deficits wherein muscles of the lower extremities are often weakened with potential sparing of the bulbocavernosus and micturition reflexes.2

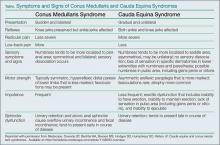

Among the many etiologies of CMS, the most common are due to compressive lesions. These include spinal trauma, neoplasm, nucleus pulposus herniation, and spinal infection. When the spinal foramen becomes either stenotic or space-occupying lesions compress, neurological function at the affected level may be compromised. In the case of CMS, neurological deficits may present as lower extremity weakness, perineal pain, or altered deep tendon reflexes (hyperreflexia or areflexia). Tactile sensation is usually spared and incontinence is frequently present. Pure lesions of the conus medullaris are uncommon and are often combined with cauda equina symptoms1 (Table).Conclusion

While many EPs are cognizant of cauda equina syndrome and its presentation, CMS is less well known and not commonly documented. Due to symptomatic overlap and epidemiological rarity of these conditions, most of the literature describing these entities combines their discussion. This case contributes to the growing body of literature to assist clinicians in the evaluation and management of CMS.

Dr Batt is an emergency medicine resident, Arrowhead Regional Medical Center, Colton, California. Dr Stone is the emergency medical services director, Travis Air Force Base, Fairfield, California.