Case

A 100-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hypothyroidism, and moderate Alzheimer dementia was brought to the ED by emergency medical services (EMS) for altered mental status after her home health aide (HHA) noted a change in the patient’s behavior. For the past few days, the patient’s appetite waned, and she became progressively more lethargic, not eating for over 24 hours. The aide activated 911 on the direction of the patient’s primary care physician. There were no reported changes to the patient’s medications which included aspirin, levothyroxine, and hydrochlorothiazide. She was unable to provide any meaningful history.

On arrival to the ED, the patient appeared comfortable in bed. She was sleepy, but easily aroused. Initial vital signs were: heart rate, 110 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 12 breaths/minute; blood pressure, 163/103 mm Hg; oral temperature, 98.2˚F. Oxygen (O2) saturation was 96% on room air. She was oriented to person only and responded appropriately to simple questions, intermittently following one-step commands. She was unable to attend and required redirection throughout the interview. (According to the aide, this behavior was different than her baseline.)

The patient’s head and neck examination were notable for some mild, boggy, periorbital edema and dry mucous membranes. Her thyroid examination was normal; her lungs were clear; and her cardiac examination revealed a 2/6 systolic ejection murmur over the second right intercostal space. Examination of the abdomen, extremities, and skin was unrevealing, and there were no gross focal neurological deficits. Her reflexes were normal throughout.

Initial assessment of this patient suggested a diagnosis of dementia and hypoactive delirium—the latter due to one or more of several possible etiologies.

Altered Mental Status

While altered mental status is a billable medical ICD-9-CM code1 used to specify a diagnosis on a reimbursement claim, it is not a disease state itself. Instead, it is a catchall phrase that incorporates any change in mental status, encompassing symptomatology that may have the largest differential diagnosis encountered in emergency medicine.

Delirium

An important category of altered mental status is delirium. The diagnostic criteria2 for delirium in DSM-V have remained essentially unchanged from DSM-IV; however, the prevalence of delirium as one of the key geriatric syndromes has grown as a result of increased research and education, particularly in the emergency medical setting. Distilled down, delirium can be defined as an acute change in mental status not caused by underlying dementia. Its cause is often multifactorial, and it is frequently an underappreciated consequence of both critical illness and the hospital environment.3

Delirium is an emergency unto itself, with an in-hospital mortality rate mirroring that of sepsis or acute myocardial infarction.4 The older-adult population is especially at risk of delirium and can present with one of three clinical subtypes: hyperactive (ie, agitated, etc), hypoactive (ie, somnolent, lethargic, stuporous, etc), and mixed type.5

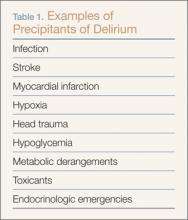

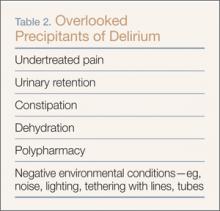

Delirium is a form of acute brain dysfunction involving a complex interaction between patient vulnerability factors and precipitating factors,6,7 resulting in either impaired cerebral metabolism and/or neurotransmitter disequilibrium. Both sets of factors must be considered. For example, delirium may develop in a particularly vulnerable 92-year-old man with moderate dementia and a mild lower leg cellulitis without signs of sepsis.The composition of factors precipitating the onset of delirium includes age, dementia, alcohol use, depression, illness severity, and drug exposure—notably benzodiazepines, opiates, and medications with anticholinergic properties.8 While major precipitants or causes of delirium, traditionally considered as potentially life-threatening acute events, are well known (Table 1), others are often overlooked (Table 2). Yet, ironically, these more frequently bypassed causes are more readily reversible, once discovered, such as inadequate pain control, urinary retention, constipation, dehydration, polypharmacy, and negative environmental conditions in the patient’s immediate surroundings. These findings have recently been corroborated.9

Hypoactive or “quiet” delirium is particularly difficult to detect because of the lack of agitation, and can therefore make the evaluation of the underlying precipitant especially challenging.The Confusion Assessment Method

Identifying delirium can be a particular challenge for emergency physicians (EPs), especially when the patient has an underlying diagnosis of dementia and the specific degree of cognitive impairment is not known. The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM)10 is the most commonly used tool in the critical care setting11 and is the only validated tool for the ED, with an 86% sensitivity and 100% specificity.12 It evaluates four elements: (1) acute onset and fluctuating course; (2) inattention; (3) disorganized thinking; and (4) altered level of consciousness. A patient must demonstrate the first two elements in addition to either the third or fourth element to be considered to have delirium.10

The CAM intensive care unit scale has the potential to be even more applicable in the ED. Recent findings support its validation.9