More recently, in April 2015, Lancet published a large RCT from 24 hospitals in the United Kingdom, comparing placebo versus 400 mcg tamsulosin and 30 mg nifedipine. The authors concluded that “tamsulosin 400 mcg and nifedipine 30 mg are not effective at decreasing the need for further treatment to achieve stone clearance in 4 weeks for patients with expectantly managed ureteric colic.”27 Another large double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, multicenter trial by Furyk et al28 in July 2015 went a step further and evaluated distal stones, which have historically caused complications requiring intervention. They concluded that there was “no benefit overall of 0.4 mg of tamsulosin daily for patients with distal ureteric calculi less than or equal to 10 mm in terms of spontaneous passage, time to stone passage, pain, or analgesia requirements. In the subgroup with large stones (5 to 10 mm), tamsulosin did increase passage and should be considered.”28 Based on these recent studies, the use of tamsulosin in patients with stones larger than 5 mm—but not those with smaller stones—appears to be an appropriate treatment option.

Patient Disposition

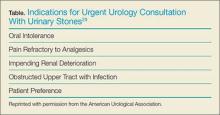

The American Urological Association cited indications for urgent/emergent urological interventions necessitating the need for inpatient admission and further workup.29 Patients who do not fall into any of the categories outlined in the Table may be seen on an outpatient basis. These patients may be treated symptomatically until they can follow up with a urologist, who will determine expectant management versus intervention.

In many communities, initial follow-up with a primary care physician (PCP), rather than a urologist, is standard for patients who are likely to pass the stone spontaneously—specifically those with nonobstructing stones <5 mm in diameter and no history of prior complicated kidney stone. Any patient discharged home with a suspected or confirmed diagnosis of nephrolithiasis should be instructed to return to the ED if he or she is unable to take the prescribed medications due to excessive nausea/vomiting; becomes febrile; develops severe pain despite oral medication; or develops any other worrisome symptoms. All of these indicate that he or she may have progressed to complicated nephrolithiasis requiring further workup and potential intervention (Table). Computed tomography should be pursued in a patient whose stone is symptomatic enough to warrant inpatient admission. For example, a patient who is febrile or whose urinalysis is suggestive of infection—in addition to a high clinical suspicion of renal colic—should undergo CT evaluation to rule out an obstructing infected stone or another possible diagnosis. Computed tomography investigation is required in any patient who presents with colicky pain or flank pain and whose condition is considered complicated.Prognosis

The majority of stones <5mm will pass spontaneously.30 Larger stones may still pass spontaneously but are more likely to require lithotripsy or other urologic intervention; therefore, patients with stones >5 mm should be referred to urology services.30

Recurrence

Patients with a first-time kidney stone have a 30% to 50% chance of disease recurrence within 5 years,31 and a 60% to 80% chance of recurrence during their lifetime.32 Those with a family history of nephrolithiasis are likely to develop an earlier onset of stones as well as experience more frequent recurrent episodes.33 Patients with recurrent disease should undergo outpatient risk stratification, including stone-composition analysis and assessment for modifiable risk factors.

Case Conclusion

The patient’s urinalysis demonstrated microscopic hematuria; blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels were within normal limits. As the patient was tachycardic and appeared mildly dehydrated, an IV infusion of 1 L normal saline was initiated, along with ketorolac and ondansetron for symptomatic relief. A POC ultrasound of the right kidney revealed mild-to-moderate hydronephrosis; the left kidney appeared sonographically normal. Since this patient had no history of nephrolithiasis, a nonenhanced CT of the abdomen was obtained, which revealed moderate, right-sided hydronephrosis and a 3-mm distal ureteral stone. Once the patient’s symptoms were controlled, she was discharged home with a prescription for ibuprofen for symptomatic relief and instructions to follow up with her PCP.

Conclusion

The evaluation and treatment of nephrolithiasis is important due to its increasing prevalence, as well as implications on costs to the health-care system and to patients themselves. The workup and treatment of nephrolithiasis has been and continues to be the subject of much controversy. Until very recently, treatment recommendations were founded on physiological theories more so than robust research. In an era where improved imaging technology is becoming more readily available in the ED, EPs should weigh the pros and cons of its utilization for common ED complaints such as nephrolithiasis.