Nail disorders are common among pediatric patients but often are underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed because of their unique disease manifestations. These conditions may severely impact quality of life. There are few nail disease clinical trials that include children. Consequently, most treatment recommendations are based on case series and expert consensus recommendations. We review inflammatory and infectious nail disorders in pediatric patients. By describing characteristics, clinical manifestations, and management approaches for these conditions, we aim to provide guidance to dermatologists in their diagnosis and treatment.

INFLAMMATORY NAIL DISORDERS

Nail Psoriasis

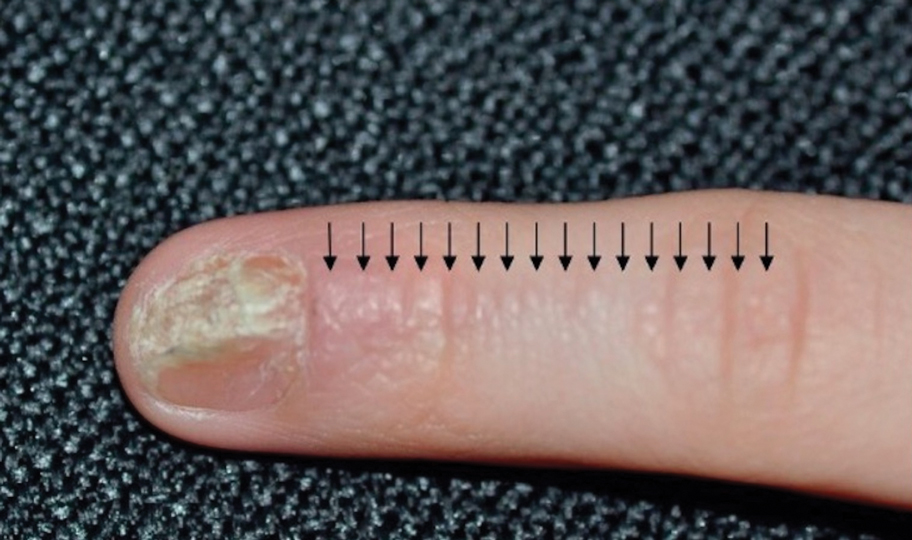

Nail involvement in children with psoriasis is common, with prevalence estimates ranging from 17% to 39.2%.1 Nail matrix psoriasis may manifest with pitting (large irregular pits) and leukonychia as well as chromonychia and nail plate crumbling. Onycholysis, oil drop spots (salmon patches), and subungual hyperkeratosis can be seen in nail bed psoriasis. Nail pitting is the most frequently observed clinical finding (Figure 1).2,3 In a cross-sectional multicenter study of 313 children with cutaneous psoriasis in France, nail findings were present in 101 patients (32.3%). There were associations between nail findings and presence of psoriatic arthritis (P=.03), palmoplantar psoriasis (P<.001), and severity of psoriatic disease, defined as use of systemic treatment with phototherapy (psoralen plus UVA, UVB), traditional systemic treatment (acitretin, methotrexate, cyclosporine), or a biologic (P=.003).4

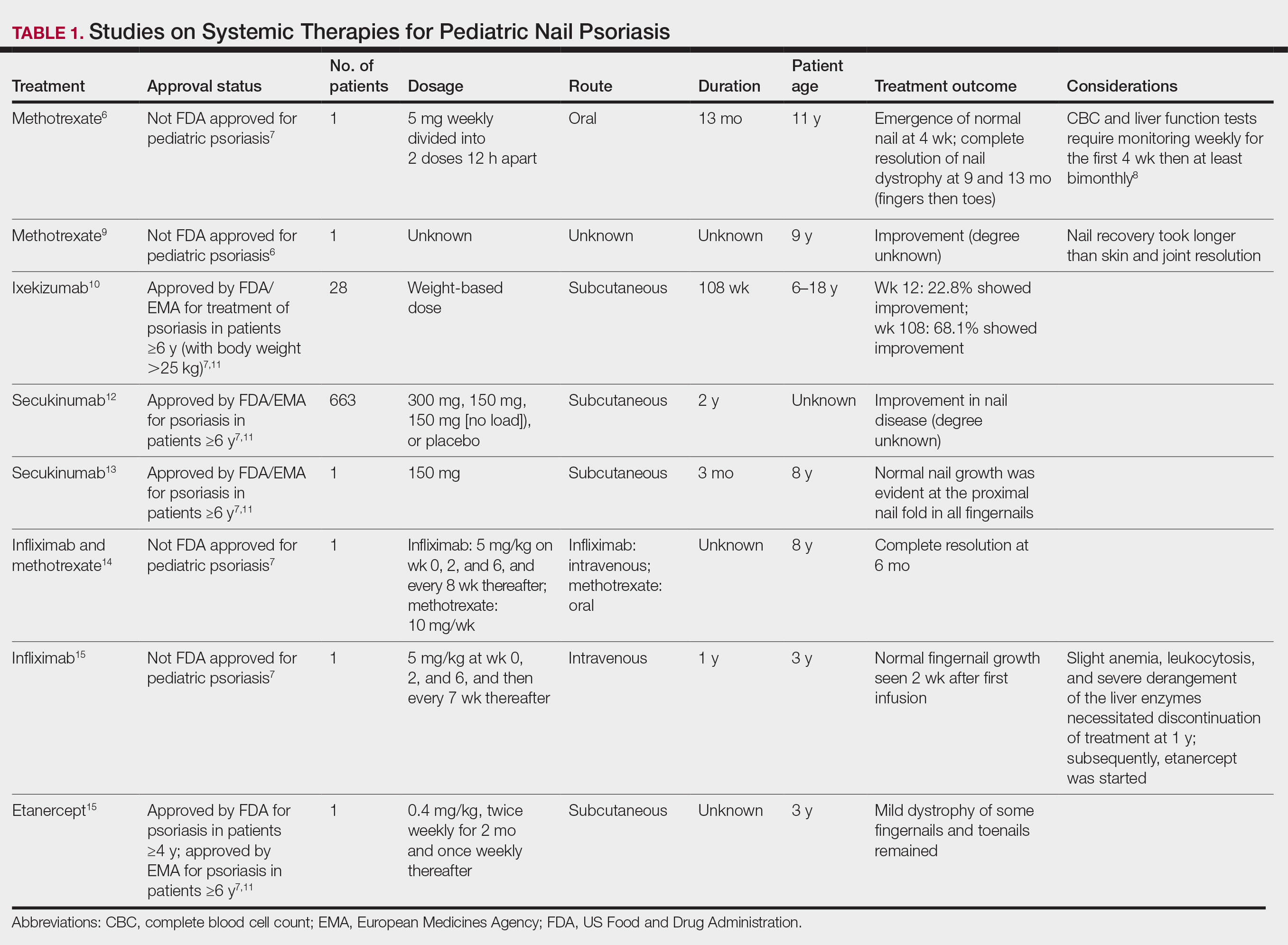

Topical steroids and vitamin D analogues may be used with or without occlusion and may be efficacious.5 Several case reports describe systemic treatments for psoriasis in children, including methotrexate, acitretin, and apremilast (approved for children 6 years and older for plaque psoriasis by the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA]).2 There are 5 biologic drugs currently approved for the treatment of pediatric psoriasis—adalimumab, etanercept, ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab—and 6 drugs currently undergoing phase 3 studies—brodalumab, guselkumab, risankizumab, tildrakizumab, certolizumab pegol, and deucravacitinib (Table 1).6-15 Adalimumab is specifically approved for moderate to severe nail psoriasis in adults 18 years and older.

Intralesional steroid injections are sometimes useful in the management of nail matrix psoriasis; however, appropriate patient selection is critical due to the pain associated with the procedure. In a prospective study of 16 children (age range, 9–17 years) with nail psoriasis treated with intralesional triamcinolone (ILTAC) 2.5 to 5 mg/mL every 4 to 8 weeks for a minimum of 3 to 6 months, 9 patients achieved resolution and 6 had improvement of clinical findings.16 Local adverse events were mild, including injection-site pain (66%), subungual hematoma (n=1), Beau lines (n=1), proximal nail fold hypopigmentation (n=2), and proximal nail fold atrophy (n=2). Because the proximal nail fold in children is thinner than in adults, there may be an increased risk for nail fold hypopigmentation and atrophy in children. Therefore, a maximum ILTAC concentration of 2.5 mg/mL with 0.2 mL maximum volume per nail per session is recommended for children younger than 15 years.16

Nail Lichen Planus

Nail lichen planus (NLP) is uncommon in children, with few biopsy-proven cases documented in the literature.17 Common clinical findings are onychorrhexis, nail plate thinning, fissuring, splitting, and atrophy with koilonychia.5 Although pterygium development (irreversible nail matrix scarring) is uncommon in pediatric patients, NLP can be progressive and may cause irreversible destruction of the nail matrix and subsequent nail loss, warranting therapeutic intervention.18

Treatment of NLP may be difficult, as there are no options that work in all patients. Current literature supports the use of systemic corticosteroids or ILTAC for the treatment of NLP; however, recurrence rates can be high. According to an expert consensus paper on NLP treatment, ILTAC may be injected in a concentration of 2.5, 5, or 10 mg/mL according to disease severity.19 In severe or resistant cases, intramuscular (IM) triamcinolone may be considered, especially if more than 3 nails are affected. A dosage of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/mo for at least 3 to 6 months is recommended for both children and adults, with 1 mg/kg/mo recommended in the active treatment phase (first 2–3 months).19 In a retrospective review of 5 pediatric patients with NLP treated with IM triamcinolone 0.5 mg/kg/mo, 3 patients had resolution and 2 improved with treatment.20 In a prospective study of 10 children with NLP, IM triamcinolone at a dosage of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg every 30 days for 3 to 6 months resulted in resolution of nail findings in 9 patients.17 In a prospective study of 14 pediatric patients with NLP treated with 2.5 to 5 mg/mL of ILTAC, 10 achieved resolution and 3 improved.16

Intralesional triamcinolone injections may be better suited for teenagers compared to younger children who may be more apprehensive of needles. To minimize pain, it is recommended to inject ILTAC slowly at room temperature, with use of “talkesthesia” and vibration devices, 1% lidocaine, or ethyl chloride spray.18

Trachyonychia

Trachyonychia is characterized by the presence of sandpaperlike nails. It manifests with brittle thin nails with longitudinal ridging, onychoschizia, and thickened hyperkeratotic cuticles. Trachyonychia typically involves multiple nails, with a peak age of onset between 3 and 12 years.21,22 There are 2 variants: the opaque type with rough longitudinal ridging, and the shiny variant with opalescent nails and pits that reflect light. The opaque variant is more common and is associated with psoriasis, whereas the shiny variant is less common and is associated with alopecia areata.23 Although most cases are idiopathic, some are associated with psoriasis and alopecia areata, as previously noted, as well as atopic dermatitis (AD) and lichen planus.22,24

Fortunately, trachyonychia does not lead to permanent nail damage or pterygium, making treatment primarily focused on addressing functional and cosmetic concerns.24 Spontaneous resolution occurs in approximately 50% of patients. In a prospective study of 11 patients with idiopathic trachyonychia, there was partial improvement in 5 of 9 patients treated with topical steroids, 1 with only petrolatum, and 1 with vitamin supplements. Complete resolution was reported in 1 patient treated with topical steroids.25 Because trachyonychia often is self-resolving, no treatment is required and a conservative approach is strongly recommended.26 Treatment options include topical corticosteroids, tazarotene, and 5-fluorouracil. Intralesional triamcinolone, systemic cyclosporine, retinoids, systemic corticosteroids, and tofacitinib have been described in case reports, though none of these have been shown to be 100% efficacious.24

Nail Lichen Striatus

Lichen striatus involving the nail is uncommon and is characterized by onycholysis, longitudinal ridging, splitting, and fraying, as well as what appears to be a subungual tumor. It can encompass the entire nail or may be isolated to a portion of the nail (Figure 2). Usually, a Blaschko-linear array of flesh-colored papules on the more proximal digit directly adjacent to the nail dystrophy will be seen, though nail findings can occur in isolation.27-29 The underlying pathophysiology is not clear; however, one hypothesis is that a triggering event, such as trauma, induces the expression of antigens that elicit a self-limiting immune-mediated response by CD8 T lymphocytes.30

Generally, nail lichen striatus spontaneously resolves in 1 to 2 years without treatment. In a prospective study of 5 patients with nail lichen striatus, the median time to resolution was 22.6 months (range, 10–30 months).31 Topical steroids may be used for pruritus. In one case report, a 3-year-old boy with nail lichen striatus of 4 months’ duration was treated with tacrolimus ointment 0.03% daily for 3 months.28

Nail AD

Nail changes with AD may be more common in adults than children or are underreported. In a study of 777 adults with AD, nail dystrophy was present in 124 patients (16%), whereas in a study of 250 pediatric patients with AD (aged 0-2 years), nail dystrophy was present in only 4 patients.32,33

Periungual inflammation from AD causes the nail changes.34 In a cross-sectional study of 24 pediatric patients with nail dystrophy due to AD, transverse grooves (Beau lines) were present in 25% (6/24), nail pitting in 16.7% (4/24), koilonychia in 16.7% (4/24), trachyonychia in 12.5% (3/24), leukonychia in 12.5% (3/24), brachyonychia in 8.3% (2/24), melanonychia in 8.3% (2/24), onychomadesis in 8.3% (2/24), onychoschizia in 8.3% (2/24), and onycholysis in 8.3% (2/24). There was an association between disease severity and presence of toenail dystrophy (P=.03).35

Topical steroids with or without occlusion can be used to treat nail changes. Although there is limited literature describing the treatment of nail AD in children, a 61-year-old man with nail changes associated with AD achieved resolution with 3 months of treatment with dupilumab.36 Anecdotally, most patients will improve with usual cutaneous AD management.