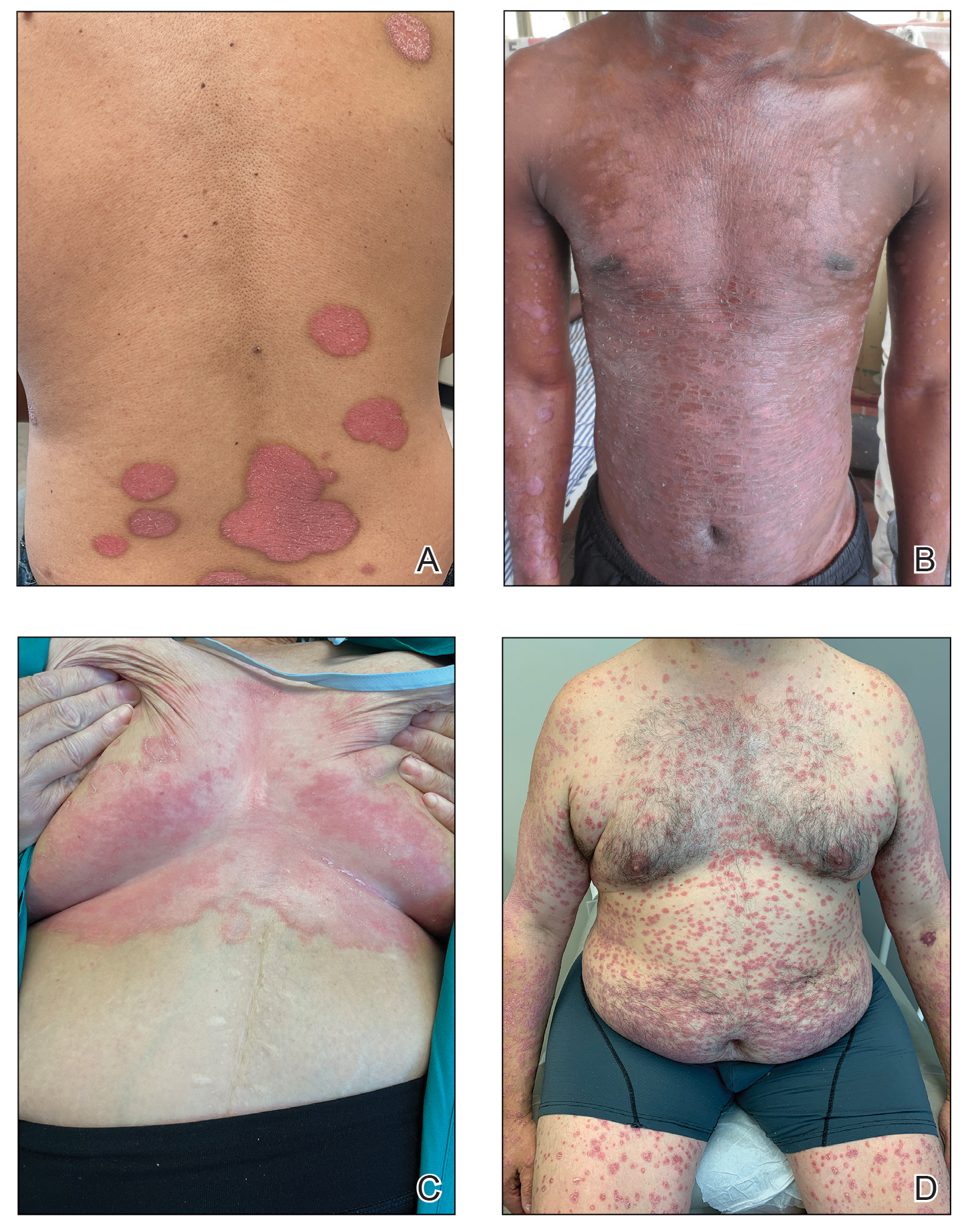

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease that affects approximately 3% of the US population.1 Plaque psoriasis comprises 80% to 90% of cases, while pustular, erythrodermic, guttate, inverse, and palmoplantar disease are less common variants (Figure 1). Psoriatic skin manifestations range from localized to widespread or generalized disease with recurrent flares. Body surface area or psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) measurements primarily focus on skin manifestations and are important for evaluating disease activity and response to treatment, but they have inherent limitations: they do not capture extracutaneous disease activity, systemic inflammation, comorbid conditions, quality of life impact, or the economic burden of psoriasis.

A common manifestation of psoriasis is psoriatic arthritis (PsA), which can involve the nails, joints, ligaments, or tendons in 30% to 41% of affected individuals (Figure 2).2,3 A growing number of psoriasis-associated comorbidities also have been reported including metabolic syndrome4; hyperlipidemia5; cardiovascular disease6; stroke7; hypertension8; obesity9; sleep disorders10; malignancy11; infections12; inflammatory bowel disease13; and mental health disorders such as depression,14 anxiety,15 and suicidal ideation.15 Psoriatic disease also interferes with daily life activities and a patient’s overall quality of life, including interpersonal relationships, intimacy, employment, and work productivity.16 Finally, the total estimated cost of psoriasis-related health care is more than $35 billion annually,17 representing a substantial economic burden to our health care system and individual patients.

The overall burden of psoriatic disease has declined markedly in the last 2 decades due to revolutionary advances in our understanding of the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis and the subsequent development of improved therapies that predominantly interrupt IL-23/IL-17 cytokine signaling; however, critical knowledge and treatment gaps persist, underscoring the importance of ongoing clinical and research efforts in psoriatic disease. We review the working immune model of psoriasis, summarize related immune discoveries, and highlight recent therapeutic innovations that are shaping psoriatic disease management.

Current Immune Model of Psoriatic Disease

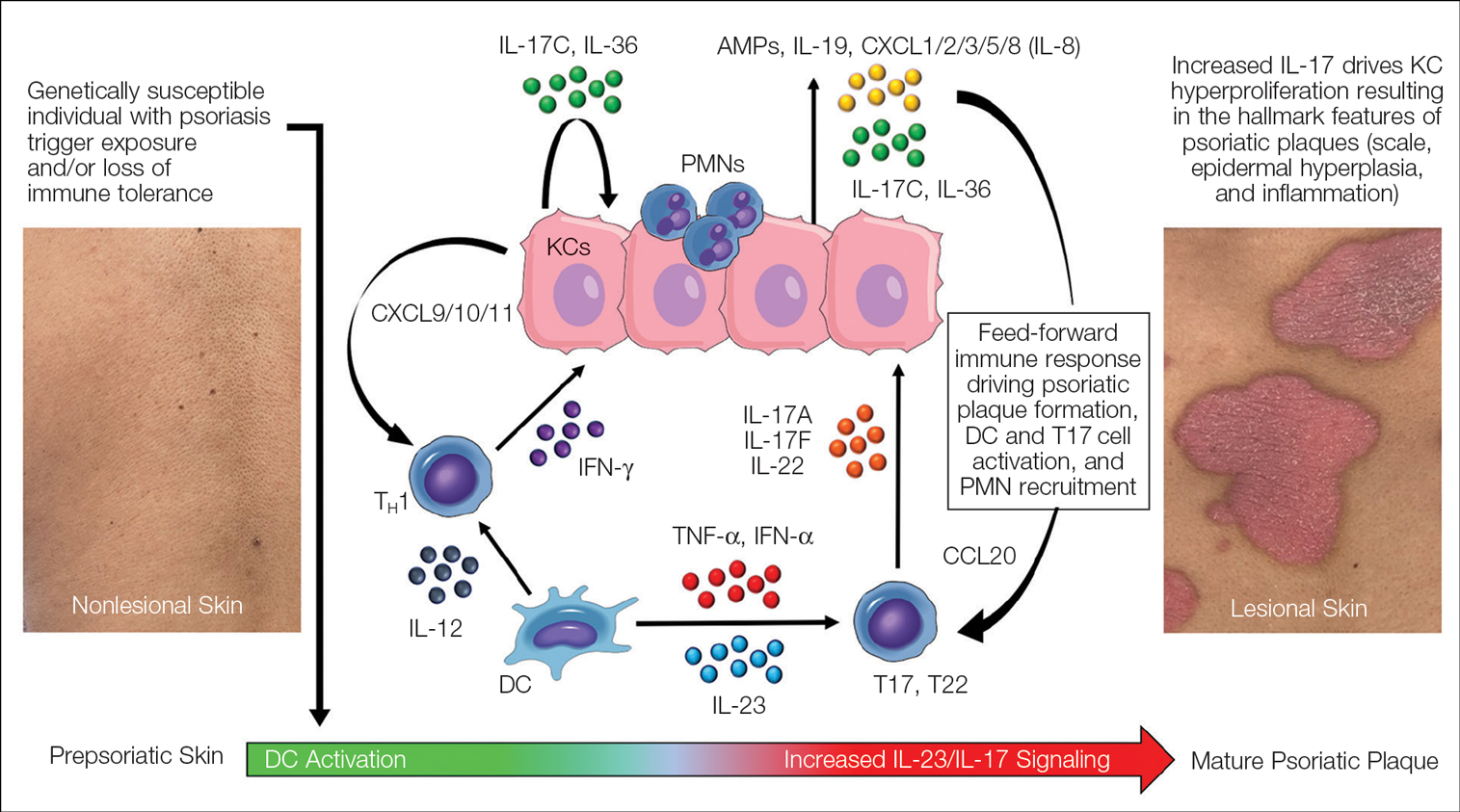

Psoriasis is an autoinflammatory T cell–mediated disease with negligible contributions from the humoral immune response. Early clinical observations reported increased inflammatory infiltrates in psoriatic skin lesions primarily consisting of both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell populations.18,19 Additionally, patients treated with broad-acting, systemic immunosuppressive medications (eg, cyclosporine, oral corticosteroids) experienced improvement of psoriatic lesions and normalization of the immune infiltrates observed in skin biopsy specimens.20,21 These early clinical findings led to more sophisticated experimentation in xenotransplant models of psoriasis,22,23 which explored the clinical efficacy of several less immunosuppressive (eg, methotrexate, anti–tumor necrosis factor [TNF] biologics)24 or T cell–specific agents (eg, alefacept, abatacept, efalizumab).25-27 The results of these translational studies provided indisputable evidence for the role of the dysregulated immune response as the primary pathogenic process driving plaque formation; they also led to a paradigm shift in how the immunopathogenesis of psoriatic disease was viewed and paved the way for the identification and targeting of other specific proinflammatory signals produced by activated dendritic cell (DC) and T-lymphocyte populations. Among the psoriasis-associated cytokines subsequently identified and studied, elevated IL-23 and IL-17 cytokine levels in psoriatic skin were most closely associated with disease activity, and rapid normalization of IL-23/IL-17 signaling in response to effective oral or injectable antipsoriatic treatments was the hallmark of skin clearance.28 The predominant role of IL-23/IL-17 signaling in the development and maintenance of psoriatic disease is the central feature of all working immune models for this disease (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Working immune model of psoriasis. Early immune events include activation of dendritic cells (DCs) and IL-17–producing T cells (T17) in the prepsoriatic (or normal-appearing) skin of individuals who are genetically susceptible and/or have exposures to known psoriasis triggers. Activation of DC and T17 populations in the skin results in increased production of tumor necrosis factor (TNF), IL-23, and IL-17 cytokines (namely IL-17A and IL-17F), which work synergistically with other immune signals (IL-12, IL-22, IL-36, TNF, interferon [IFN]) to drive keratinocyte (KC) hyperproliferation. In response to upregulated IL-17 signaling, substantial increases in keratinocyte-derived proteins (antimicrobial peptides, IL-19, IL-36, IL-17C) and chemotactic factors (chemokine [C-C motif] ligand 20 [CCL20], chemokine [C-C motif] ligand 1/2/3/5/8 [CXCL1/2/3/5/8][or IL-8]) facilitate further activation and recruitment of T17 and helper T cell (TH1) lymphocytes, DCs, macrophages, and polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) into the skin. The resultant inflammatory circuit creates a self-amplifying or feed-forward immune response in the skin that leads to the hallmark clinical features of psoriasis and sustains the mature psoriatic plaque.

Psoriasis-Associated Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors

The exact sequence of events that lead to the initiation and formation of plaque psoriasis in susceptible individuals is still poorly understood; however, several important risk factors and key immune events have been identified. First, decades of genetic research have reported more than 80 known psoriasis-associated susceptibility loci,29 which explains approximately 50% of psoriasis heritability. The major genetic determinant of psoriasis, HLA-C*06:02 (formerly HLA-Cw6), resides in the major histocompatibility complex class I region on chromosome 6p21.3 (psoriasis susceptibility gene 1, PSORS1) and is most strongly associated with psoriatic disease.30 Less common psoriasis-associated susceptibility genes also are known to directly or indirectly impact innate and adaptive immune functions that contribute to the pathogenesis of psoriasis.

Second, several nongenetic environmental risk factors for psoriasis have been reported across diverse patient populations, including skin trauma/injury, infections, alcohol/tobacco use, obesity, medication exposure (eg, lithium, antimalarials, beta-blockers), and stress.31 These genetic and/or environmental risk factors can trigger the onset of psoriatic disease at any stage of life, though most patients develop disease in early adulthood or later (age range, 50–60 years). Some patients never develop psoriasis despite exposure to environmental risk factors and/or a genetic makeup that is similar to affected first-degree relatives, which requires further study.

Prepsoriatic Skin and Initiation of Plaque Development

In response to environmental stimuli and/or other triggers of the immune system, DC and resident IL-17–producing T-cell (T17) populations become activated in predisposed individuals. Dendritic cell activation leads to the upregulation and increase of several proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF, interferon (IFN) α, IFN-γ, IL-12, and IL-23. Tumor necrosis factor and IL-23 play a vital role in psoriasis by helping to regulate the polarization and expansion of T22 and T17 cells in the skin, whereas IL-12 promotes a corresponding type 1 inflammatory response.32 Increased IL-17 and IL-22 result in alteration of the terminal differentiation and proliferative potential of epidermal keratinocytes, leading to the early clinical hallmarks of psoriatic plaques. The potential contribution of overexpressed psoriasis-related autoantigens, such as LL-37/cathelicidin, ADAMTSL5, and PLA2G4D,33 in the initiation of psoriatic plaques has been suggested but is poorly characterized.34 Whether these specific autoantigens or others presented by HLA-C variants found on antigen-presenting cells are required for the breakdown of immune tolerance and psoriatic disease initiation is highly relevant but requires further investigation and validation.