Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

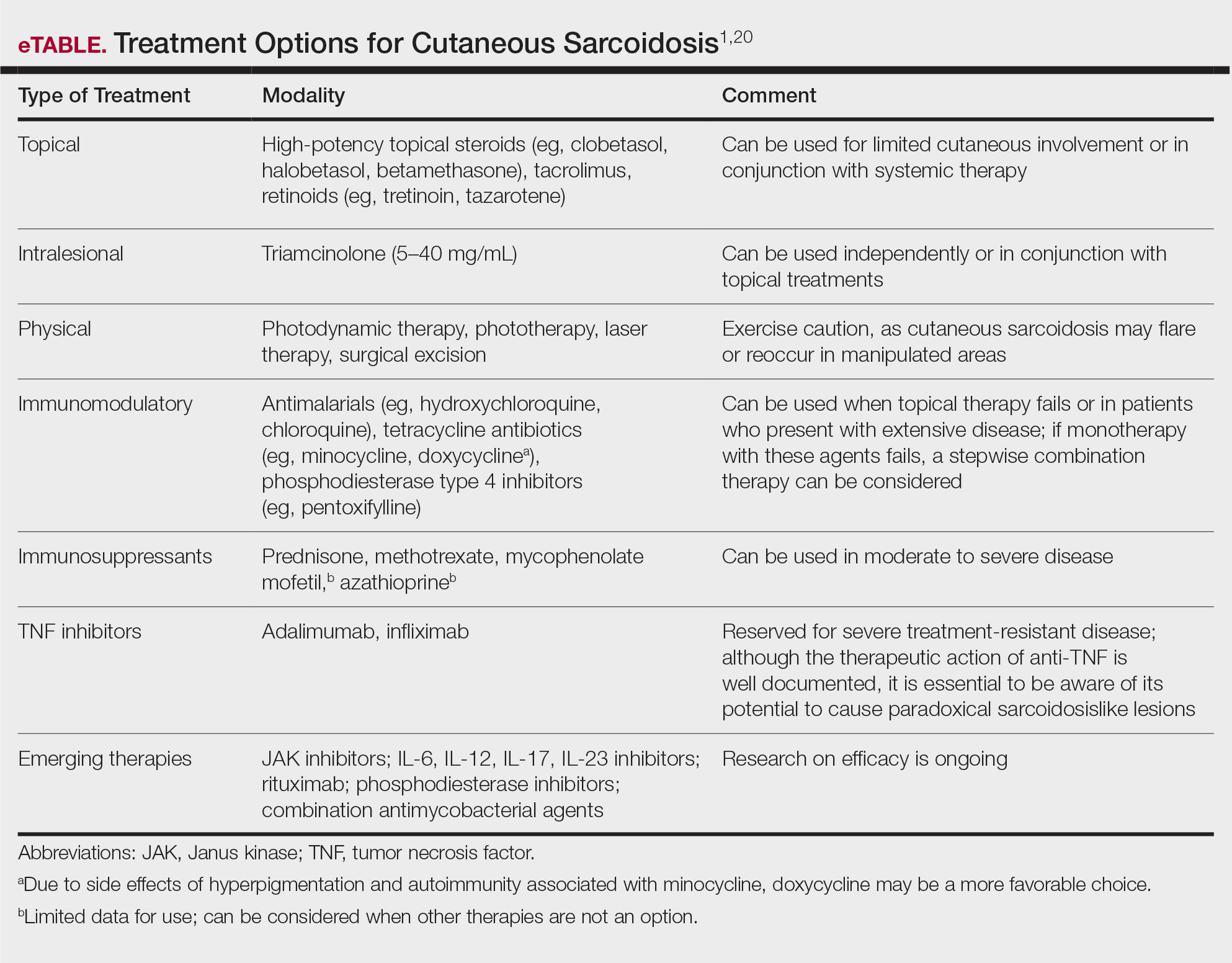

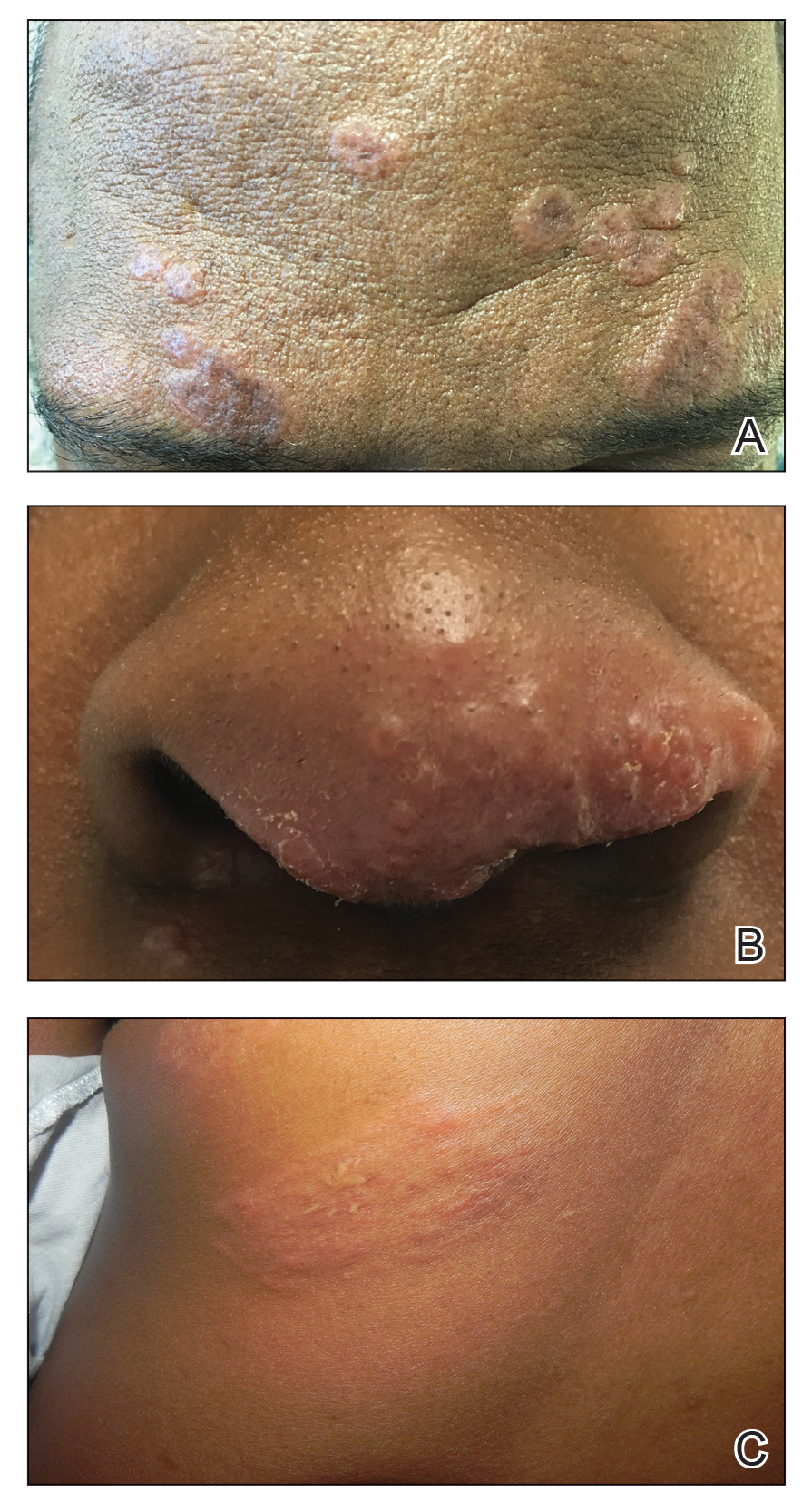

Cutaneous sarcoidosis protean morphology is considered an imitator of many other skin diseases. The most common sarcoidosis-specific skin lesions include papules and papulonodules (Figure, A), lupus pernio (Figure, B), plaques (Figure, C), and subcutaneous nodules. Lesions typically present on the face, neck, trunk, and extremities and are associated with a favorable prognosis. Lupus pernio presents as centrofacial, bluish-red or violaceous nodules and can be disfiguring (Figure, B). Subcutaneous nodules occur in the subcutaneous tissue or deep dermis with minimal surface changes. Sarcoidal lesions also can occur at sites of scar tissue or trauma, within tattoos, and around foreign bodies. Other uncommon sarcoidosis-specific skin lesions include ichthyosiform, hypopigmented, atrophic, ulcerative and mucosal lesions; erythroderma; alopecia; and nail sarcoidosis.18

A, Erythematous to violaceous, flat papules and small plaques with some scaling across the forehead in a patient with sarcoidosis. B, Scattered scaly papules and subcutaneous plaques damaging the nasal alar cartilage in a patient with lupus pernio. C, Two flesh-colored to faintly erythematous plaques on the mid back—one with a biopsysite scar within the lesion—in a patient with plaque sarcoidosis.

When cutaneous sarcoidosis is suspected, the skin serves as an easily accessible organ for biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.1 Sarcoidosis-specific skin lesions are histologically characterized as sarcoidal granulomas with a classic noncaseating naked appearance comprised of epithelioid histocytes with giant cells amidst a mild lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate. Nonspecific sarcoidosis skin lesions do not contain characteristic noncaseating granulomas. Erythema nodosum is the most common nonspecific lesion and is associated with a favorable prognosis. Other nonspecific sarcoidosis skin findings include calcinosis cutis, clubbing, and vasculitis.18

Workup

Due to the systemic nature of sarcoidosis, dermatologists should initiate a comprehensive workup upon diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis, which should include the following: a complete in-depth history, including occupational/environmental exposures; a complete review of systems; a military history, including time of service and location of deployments; physical examination; pulmonary function test; high-resolution chest computed tomography19; pulmonology referral for additional pulmonary function tests, including diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide and 6-minute walk test; ophthalmology referral for full ophthalmologic examination; initial cardiac screening with electrocardiogram; and a review of symptoms including assessment of heart palpitations. Any abnormalities should prompt cardiology referral for evaluation of cardiac involvement with a workup that may include transthoracic echocardiogram, Holter monitor, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium contrast, or cardiac positron emission tomography/computed tomography; a complete blood cell count; comprehensive metabolic panel; urinalysis, with a 24-hour urine calcium if there is a history of a kidney stone; tuberculin skin test or IFN-γ release assay to rule out tuberculosis on a case-by-case basis; thyroid testing; and 25-hydroxy vitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D screening.1

Treatment

Cutaneous sarcoidosis is treated with topical or intralesional anti-inflammatory medications, immunomodulators, systemic immunosuppressants, and biologic agents. Management of cutaneous sarcoidosis should be done in an escalating approach guided by treatment response, location on the body, and patient preference. Response to therapy can take upwards of 3 months, and appropriate patient counseling is necessary to manage expectations.20 Most cutaneous sarcoidosis treatments are not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for this purpose, and off-label use is based on available evidence and expert consensus (eTable).

An important consideration for treating sarcoidosis in active-duty servicemembers is the use of immunosuppressants or biologics requiring refrigeration or continuous monitoring. According to Department of Defense retention standards, an active-duty servicemember may be disqualified from future service if their condition persists despite appropriate treatment and impairs their ability to perform required military duties. A medical evaluation board typically is initiated on any servicemember who starts a medication while on active duty that requires frequent monitoring by a medical provider, including immunomodulating and immunosuppressant medications.21

Final Thoughts

Military servicemembers put themselves at risk for acute bodily harm during deployment and also expose themselves to occupational hazards that may result in chronic health conditions. The VA’s coverage of new presumptive diagnoses means that veterans will receive extended care for conditions presumptively acquired during military service, including sarcoidosis. Although there are no conclusive data on whether exposure while on deployment overseas causes sarcoidosis, environmental exposures should be considered a potential cause. Patients with confirmed cutaneous sarcoidosis should undergo a complete workup for systemic sarcoidosis and be asked about their history of military service to evaluate for coverage under the PACT Act.