Making a ‘bright spot’

Using these truths to construct a framework for effective inpatient collaborations, we set about piloting the following model. Please note that the purpose of this pilot project was not to have the intervention stand up to the rigors of scrutiny demanded by a clinical trial. Our intent was to see if we could create a "bright spot" for pain management, cobbling together existing resources, with the hope that hospital leadership would support us with new resources should we demonstrate a promising model.

Seton Medical Center is a large, urban hospital with providers from both the community and an academic medical group practice. We sought buy in for this project with the hospitalists, surgeons, pharmacy, nursing staff, and leadership. The pilot lasted for 1 month and took place on two med-surg units. Currently, there is no dedicated pain team in this hospital. The disciplines that provided pain management were anesthesia, behavioral health, palliative care, and physical medicine, and rehabilitation. The proposal to the hospitalists and surgeons was that once the pain team was involved all pain management decisions through the responsible pain team in an attempt to bring clarity and consistency to the pain plan.

• Consults. Consults were triggered one of three ways. All required a physician order and allowed the physician to opt-out if they disagreed with potential consults generated from options 2 or 3.

Option 1 – Traditional route: The provider saw a need for assistance with pain management and puts in the order.

Option 2 – Nurse initiated: The nurse felt as though pain was uncontrolled or there were other concerns about pain.

Option 3 – Patient initiated: After 48 hours of admission, patients experiencing pain were asked if they would like to visit with someone from the pain team.

• Hotline. A pain hotline was set up for a "one call, that’s all" approach. This obviated the need for those calling us to be familiar with which specialty would be most appropriate for managing a specific painful condition. Prior to the start of the pilot, each specialty agreed upon which etiologies of pain they would be primarily responsible for managing. For example, if it was perioperative pain, then anesthesia would be the primary pain service; if the diagnosis was pain that was related to a neoplastic process, then palliative care would be deployed.

• First contact. Initial encounters with the patient were through an advance practice nurse (APN). The APN was familiar with the purview of each specialty. After quickly assessing the patient, the nurse would distribute a leaflet to the patient and families that provided education about pain, including expectations, limitations, and a definition of how the pain team functions. For instance, they were provided with an explanation of why and when we change the route of administration of opioids from IV to PO. The APN would then activate the proper service, which would take ownership of pain management for that patient while they were hospitalized. We frequently involved colleagues from the different pain specialties to provide a comprehensive service. For example, when our team would see a patient with pain related to cirrhosis but they also had poor coping mechanisms, we would involve our behavioral health colleagues.

• Discharge planning. We sought to have a specific pain discharge plan documented in each patient’s progress note prior to leaving the hospital. This included which medications we recommend, the written prescriptions, and who would be responsible for continued management of the pain after discharge. If this were a primary care doctor or specialist that knows the patient we personally contacted that provider to assure that they concurred with our plans. If the patient had no such provider or their provider was uncomfortable managing the pain then we saw them as an outpatient in our respective clinics within 2 weeks of their hospital release.

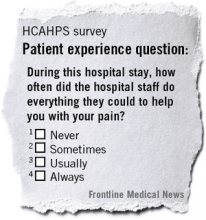

We constructed our metrics with the awareness that pain scores do not paint a picture reflective of the patient experience or quality of care. We believe that, especially in the CP population, that less emphasis will be placed on pain scores and more attention given to some of these other markers of effectiveness. Metrics included pain scores, patient’s ability to function, satisfaction through HCAHPS, whether or not a documented pain discharge plan was in the medical record, tolerability, safety measures, and pharmacy use. While a detailed analysis of our results is beyond the scope of this piece, we were pleased with our data. For instance, 91% of our patients had a specific pain discharge plan documented.