DISCUSSION

Amiodarone, a highly effective antiarrhythmic drug, is FDA approved for suppressing ventricular fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia. It is also used off-label as a second- or third-line choice for atrial fibrillation.1

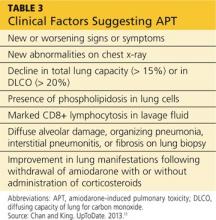

Standard of care requires that, prior to starting amiodarone therapy, patients have a baseline chest x-ray and PFTs with diffusing capacity performed. Thereafter, the patient should be monitored with annual chest x-rays, with one performed promptly if new symptoms develop. Serial PFTs have not offered any benefit for monitoring, but a decrease of more than 15% in total lung capacity or more than 20% in diffusing capacity from baseline is consistent with APT.2

Adverse effects, both cardiac and noncardiac, are common with amiodarone therapy. They include proarrhythmias, bradycardia, and heart block, as well as thyroid and liver dysfunctions; dermatologic conditions such as blue-gray discoloration of the skin and photosensitivity; neurologic effects such as ataxia, paresthesias, and tremor; ocular problems, including corneal microdeposits; gastrointestinal problems such as nausea, anorexia, and constipation; and lung problems such as pulmonary toxicity, pleural effusion, and pleural thickening.3-6 Of these, pulmonary toxicity is the most severe and life threatening.7

APT, also known as amiodarone pneumonitis and amiodarone lung, typically manifests from a few months to a year and a half after treatment is commenced.6 APT can occur even after the drug is discontinued, because amiodarone has a very long elimination half-life of approximately 15 to 45 days and a tendency to concentrate in organs with high blood perfusion and in adipose tissues.8 Patients taking 400 mg/d for two months or longer or 200 mg/d for more than two years are considered at higher risk for APT.9 The severity of disease appears to correlate with the cumulative dose and length of treatment.10

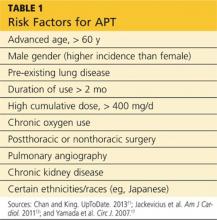

Numerous risk factors for pulmonary toxicity have been reported, including high drug dosage, pre-existing lung disease, patient age, and prior surgery (see Table 1).11 According to an analysis of a database of 237 patients, only age and duration of amiodarone therapy were significant risk factors for APT.9 Its incidence is not precisely known; reported rates range from 1% to 17%.6,12,13

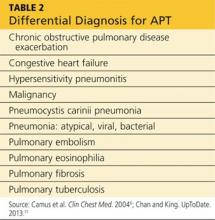

Presentation with such nonspecific symptoms as shortness of breath, nonproductive cough, fatigue, hypoxia, and general malaise is typical for many pulmonary and cardiac illnesses (see Table 2), making APT difficult to diagnose.14 Occasionally, rapid onset with progression to pneumonitis and respiratory failure masquerades as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).15

Notable, however, is that APT can manifest with nonproductive cough and dyspnea in 50% to 75% of cases. In addition, presenting symptoms will include fever (33% to 50% of cases) with associated malaise, fatigue, chest pain, and weight loss. In patients with APT, the physical exam usually reveals bilateral crackles on inspiration, but diffuse rales may be heard as well.11

Laboratory studies are not very helpful in diagnosing APT. Patients may present with nonspecific elevated WBCs without eosinophilia and an elevated LDH level.11 An elevated ESR may be detected before symptoms of APT manifest and can be present at the time of diagnosis.6

Imaging studies are far more helpful and specific in diagnosing APT. The typical chest x-ray shows bilateral patchy diffuse infiltrates.12 CT of the chest is usually more revealing, demonstrating ground glass opacities in the periphery and subpleural thickening, especially where infiltrates are denser. This thickening may result in pleuritic chest pain.6

The right upper lobe is more often affected in these cases than the left lung.6 Numerous pulmonary nodules in the upper lobes are found rarely and can be confused with lung cancer. These nodules are likely the result of an accumulation of the drug in areas of previous inflammation; a lung mass should prompt the addition of APT in the differential.2,16

APT is a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring clinical suspicion, drug history, imaging, and consideration of the differential. The presence of three or more clinical factors supports a diagnosis of APT (see Table 3).11