Secondary dyspareunia, or painful intercourse that occurs after a history of pain-free sex, is most often caused by either vaginal atrophy or vulvodynia. Vaginal atrophy, resulting from low circulating estrogen, may cause symptoms of itching, dryness, and irritation; it is experienced by about 40% of postmenopausal women,10 as well as many premenopausal women who take low-dose estrogen oral contraceptives.11-13

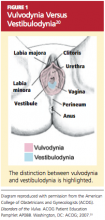

Vulvodynia, which affects 16% of women, refers to vulvar pain, usually described as a burning or cutting sensation, with no significant physical changes seen on examination.7,8,14 Vulvodynia may be localized or generalized to the entire vulva and provoked or unprovoked. Vestibulodynia, which is a subtype of vulvodynia, refers to unexplained pain in the vestibule of the vaginal introitus; the only physical finding may be erythema. Provoked vestibulodynia is the most common form of introital pain, affecting 3% to 15% of women.15-17

Both vulvodynia and vestibulodynia have been explained as neurosensory disorders that are triggered by stimuli such as repeated vaginal infections or long-term use of low-dose estrogen oral contraceptives.12 Other less common vulvar conditions that cause dyspareunia include noninfectious skin conditions, such as dermatitis and lichenoid conditions.18 Many women also experience painful vulvar or vaginal irritation due to sensitivity to spermicide on condoms; latex allergy; and/or ingredients in some lubricants, soaps, body perfumes, detergents, or douches.18,19 Less common vulvovaginal conditions associated with dyspareunia include anomalies, infection, radiation effects, and scarring injuries (see Figure 120).

In some cases, dyspareunia is caused by conditions involving the uterus, ovaries, bladder, or rectum. Uterine conditions include myomas, adenomyosis, endometriosis, retroversion, or retroflexion.21,22 In the case of prolapsed uterus, contact with the cervix or uterus may result in what is described by the patient as “an electric shock” or “stabbing” or “shooting” pain.23

Ovarian cysts, intermittent ovarian torsion, and hydrosalpinx can each cause painful intercourse. Associated bladder and urinary tract conditions include urinary tract infection; urethral caruncle or diverticulum; urethral atrophy resulting from low circulating estrogen in women of any age; and interstitial cystitis, which is usually associated with pain after intercourse and/or during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.22,24 Anorectal inflammatory conditions, such as lichen sclerosis, Crohn’s disease, and severe constipation with or without hemorrhoids, may be causes of dyspareunia. In rare instances, dyspareunia may be a sign of a tumor in the urogenital or lower GI tract.25,26

Dyspareunia may be indicative of pelvic adhesions resulting from surgery or inflammatory conditions, such as current or past pelvic inflammatory disease.22 The majority (50% to 80%) of women with endometriosis complain of pain with deep thrusting during coitus,27 which is most severe before menstruation and in sexual positions in which the woman has less control over the depth and force of penetration.

Musculoskeletal conditions associated with dyspareunia include scoliosis, levator ani muscle myalgia, and levator ani/pelvic floor musculature spasm.28,29 These may be primary or secondary to another condition that causes deep dyspareunia and may involve pain in the lower back, sacroiliac joint, piriformis, or obturator internus.28

Neurologic conditions, such as pudendal neuralgia and sciatica, can also be associated with pelvic floor injuries during childbirth, nerve entrapment, or straddle injuries.12 Genital piercing and cutting can lead to painful neuromas, neurofibromas, and neuralgia.30

Finally, whether or not identifiable physical causes exist, the experience of pain can be triggered or exacerbated by psychosocial factors. When vaginal penetration has been painful, a pattern of anticipatory anxiety and fear is common. Certain cognitive styles are also associated with dyspareunia. Examples include hypervigilance (“I’m just waiting for it to start hurting”) and catastrophizing (“This hurts so much that I’m going to have to give up having sex altogether”).31,32

Generalized anxiety and somatization, defined as the tendency to experience a variety of physical symptoms without physical origin in reaction to stress, may predispose a woman to experience dyspareunia.1,31 Relationship distress is another related psychosocial factor.33 Even in relationships that are for the most part positive, a woman’s reluctance to communicate her sexual needs may result in foreplay and stimulation that are inadequate to achieve arousal and lubrication.

EVALUATION OF THE PATIENT

Any woman who reports pain during intercourse should undergo a careful history and physical exam directed toward detection of signs of vaginal atrophy (especially women who are menopausal or taking oral estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives), vulvodynia, vestibulodynia, and other physical and psychological conditions that can cause sexual pain.

A sexual pain history should be taken, focusing on pain experienced with intercourse and/or with tampon or speculum insertion. Pain assessment includes location, intensity, quality (burning, shooting, or dull pain), and duration of the pain. The clinician should ask whether penetrative sex has ever been pain-free to assess for a lifelong or situational condition. Pain frequency, kinds of associated activities, and factors that exacerbate or alleviate the symptom of pain should be clarified. Assessment should include questions about relationship distress; sexual pain can exert negative impact on the relationship, which can then exacerbate sexual pain by impairing arousal. It is important to ascertain whether pain occurs or has occurred with all of the patient’s sexual partners.