CORE PRINCIPLES FOR HANDLING FRUSTRATING CASES

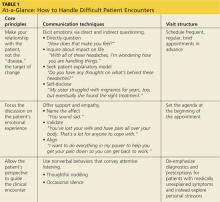

A useful approach to the difficult patient encounter, detailed in Table 1, is based on three key principles:

• The clinician-patient relationship should be the target for change.

• The patient’s emotional experience should be an explicit focus of the clinical interaction.

• The patient’s perspective should guide the clinical encounter.

In our experience, when the interaction between patient and clinician shifts from searching for specific pathologies to building a collaborative relationship, previously recalcitrant symptoms often improve.

Use these communication techniques

There are two main ways to elicit a conversation about personal issues, including emotions, with patients. One is to directly ask patients to describe the distress they are experiencing and elicit the emotions connected to this distress. The other is to invite a discussion about emotional issues indirectly, by asking patients how the symptoms affect their lives and what they think is causing the problem or by selectively sharing an emotional experience of your own.

Once a patient has shared emotions, you will need to show support and empathy in order to build an alliance. There is more than one way to do this, and methods can be used alone or in combination, depending on the particular situation. (You’ll find examples in Table 1.)

Name the affect. The simple act of naming the patient’s affect or emotional expression (eg, “You sound sad”) is surprisingly helpful, as it lets patients know they have been “heard.”

Validate. You can also validate patients like Mr. E, Mr. A, and Ms. S by stating that their emotional reactions are legitimate, praising them for how well they have coped with difficult symptoms, and acknowledging the seriousness and complexity of their situations.

Align. Once a patient expresses his or her interests and goals, aligning yourself with them (eg, “I want to do everything in my power to help you reduce your pain …”) will elicit hope and improve patient satisfaction.

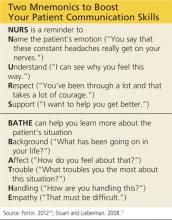

And two mnemonic devices—detailed in the box above—can help you improve the way you communicate with patients.10,11

Communication can also be nonverbal, such as thoughtful nodding or a timely therapeutic silence. The former is characterized by slow, steady, and purposeful movement accompanied by eye contact; in the latter case, you simply resist the urge to immediately respond after a patient has revealed something emotionally laden, and wait a few seconds to take in what has been said.

HOW TO PROVIDE THERAPEUTIC STRUCTURE

Family practice clinicians can further manage patient behaviors that they find bothersome by implementing changes in the way they organize and conduct patient visits. Studies of patients with complex somatic symptoms offer additional hints for the management of frustrating cases. The following strategies can lead to positive outcomes, including a decrease in disability and health care

costs.12

Schedule regular brief visits. Mr. E, Mr. A, and Ms. S should have frequent and regular, but brief, appointments (eg, 15 minutes every two weeks for two months). Proactively schedule return visits, rather than waiting for the patient to call for an appointment prn.11 Sharing this kind of plan gives such patients a concrete time line and clear evidence of support. Avoid the temptation to schedule difficult cases for the last time slot of the day, as going over the allotted time can insidiously give some patients the expectation of progressively longer visits.

Set the agenda. To prevent “doorknob questions” like Ms. S’s new symptoms, reported just as you’re about to leave the exam room, the agenda must be set at the outset of the visit. This can be done by asking, “What did you want to discuss today?”, “Is there anything else you want to address today?”, or “What else did you need taken care of?”13

Explicitly inquiring about patient expectations at the start of the visit lets patients like Ms. S know that they are being taken seriously. If the agenda still balloons, you can simply state, “You deserve more than 15 minutes for all these issues. Let’s pick the top two for today and tackle others at our next visit in two weeks.” To further save time, you can ask the patient to bring a symptom diary or written agenda to the appointment. We’ve found that many anxious patients benefit from this exercise.

Avoid the urge to act. When a patient has unexplained symptoms, effective interventions require clinicians to avoid certain “reflex” behaviors—repeatedly performing diagnostic tests, prescribing medications for symptoms of unknown etiology, insinuating that the problem is “in your head,” formulating ambiguous diagnoses, and repeating physical exams.12 Such behaviors tend to reinforce the pathology in patients with unexplained symptoms. The time saved avoiding these pitfalls is better invested in exploring personal issues and stressors.