SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Heart failure is characterized by a constellation of signs and symptoms of pulmonary and/or systemic venous congestion caused by impaired ability of the heart to fill with or eject blood in proportion to the metabolic needs of the body.1 Manifestations include fatigue, dyspnea, fluid retention, and cachexia, and patients can present anywhere on the spectrum—from asymptomatic at rest to severely symptomatic.

Symptoms

In both reduced LVEF and preserved LVEF HF, common early symptoms include dyspnea and fatigue on exertion, with or without some degree of lower-extremity swelling.2 Lack of treatment and disease progression increase symptom severity—to the extent that dyspnea and fatigue start to occur at rest. Reviewing the anatomic classifications/findings of HF facilitates understanding of the clinical symptoms.

Right HF. Right ventricular dysfunction is rarely found in isolation; when symptoms are present, further evaluation of the left ventricle and the pulmonary system (to look for cor pulmonale) is warranted. Right HF is associated with an inability to manage venous return and move volume into the pulmonary circuit. This produces the predominant symptom of fluid retention. Peripheral edema is a cardinal symptom of right HF; edema can also present systemically, mostly as hepatic congestion or general gastrointestinal complaints resulting from impaired gastrointestinal perfusion.9

Left HF. Left ventricular dysfunction is the more common anatomic finding in HF and is often generalized to represent all cases. The dysfunction can be found in isolation and is actually the leading cause of right HF. In left HF (regardless of etiology), the heart does not produce enough “forward” pressure (ie, cannot pump or fill with enough blood) for the cardiovascular system to remain in balance. Thus, “back” pressure into the pulmonary circuit develops.

The combination of insufficient systemic perfusion capability with a dysfunctional left pump means that the most common symptom in all cases of left HF is shortness of breath—specifically, exertional dyspnea. Dyspnea can progress to orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and, finally, dyspnea at rest. Patients often present with a cough that is worse while lying down and that can be nonproductive or productive, depending on volume status.9,10

Signs

Vital signs range from normal to indicative of shock. Increased sympathetic nervous system activity is common; this may manifest as coldness of the extremities and diaphoresis. Keep in mind that HF is a clinical diagnosis: The physical examination, focusing on peripheral signs, is key in all HF patients for both diagnosis and management.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical exam includes the heart, neck, lungs, abdomen, and extremities. The cardiac exam includes evaluation for hypertrophy, by palpating for the point of maximum impulse to assess for lifts, heaves, valvular disease, and S3 and S4 sounds. Respiratory, abdominal, and extremity exams all focus on the evaluation of fluid status and edema.

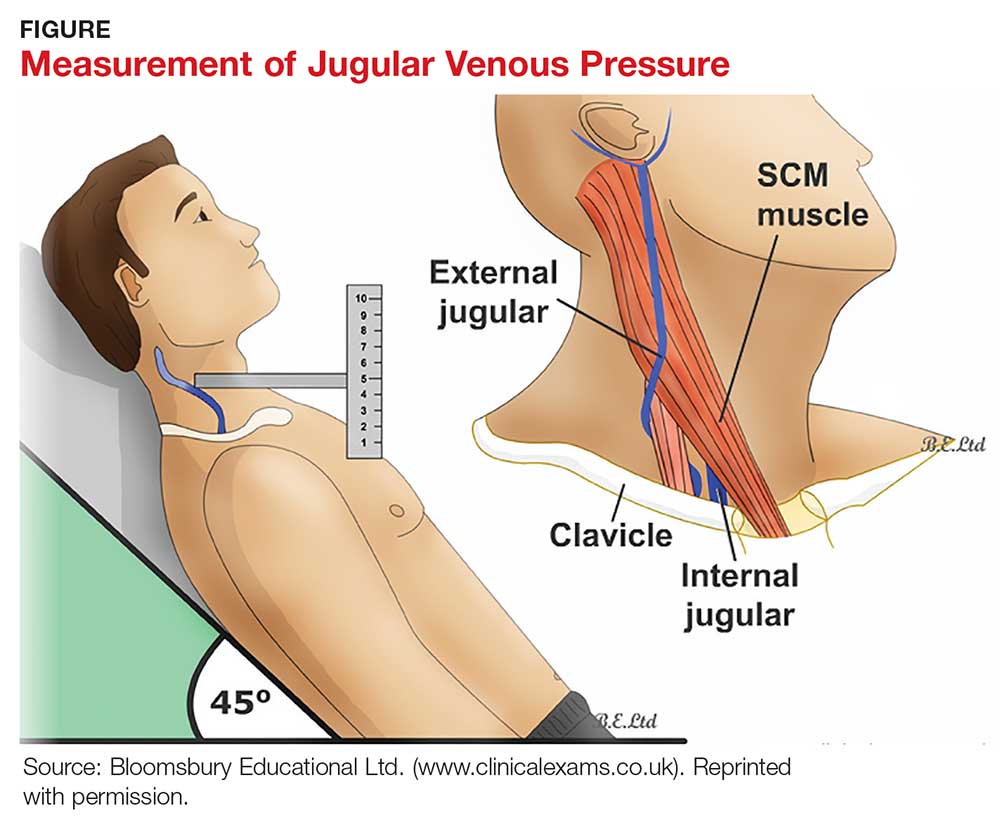

A key, often underutilized measurement is jugular venous pressure (JVP). Elevated JVP has been identified as the most specific sign of fluid overload in HF and the most important physical finding in the initial and subsequent examinations of a patient with HF.11 (For good reason, clinicians who treat patients with HF must be able to recognize volume overload and hypovolemia; euvolemia allows patients to remain symptom-free and makes it possible to initiate life-prolonging therapy, which will be discussed in the Treatment section.2) JVP is an indirect measure of pressure within the right side of the heart (central venous pressure).

Most texts on performing the physical exam recommend measuring JVP using the right internal jugular vein. However, use of the internal jugular vein is limiting in HF patients, because it is covered by the sternocleidomastoid muscle for most of its course in the neck and visible only in a small triangle between the two heads in the root of the neck (see Figure). Conversely, the external jugular veins are subcutaneous along their entire course and pulsations are easily visible—but superficial and prone to external pressure and internal occlusion. A nonpulsatile, distended jugular vein should not be used to estimate venous pressure.2

What, then, is the best method? Vinayak et al evaluated the comparative effectiveness of the internal and external jugular veins for detection of central venous pressure. They found that the external jugular vein is easier to visualize and has excellent reliability for determining low and high venous pressures.12

The process for estimating JVP is the same regardless of which jugular vein (internal or external) is used. The technique is described by Bickley in Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking:

The patient lies supine and at an angle between 30° and 45°. Turn the head slightly, and with tangential lighting, identify the external and internal jugular veins. Identify the highest point of pulsation in the right jugular vein and extend a long rectangular object or card horizontally from this point and a centimeter ruler vertically from the sternal angle, making an exact right angle. Measure the vertical distance (in centimeters) above the sternal angle where the horizontal object crosses the ruler and add this distance to 4 cm. Measurements of > 3-4 cm above the sternal angle or > 8 cm in total distance are considered elevated.13

Continue to: DIAGNOSTIC AND SCREENING TESTS